E5: Inside the coach's eye

With Bart Dingenen

Dr. Bart Dingenen takes us inside the world where cutting-edge research meets real-world physiotherapy with a special focus on ACL injuries and rehab. From mastering biomechanics to embracing new approaches in motor learning, Bart shares how clinicians can sharpen their critical thinking and develop a true “coach’s eye.”

We explore the importance of ecological validity in testing, the smart use of technology in practice, and the art of managing expectations, especially with young athletes. Bart also dives into why rehabilitation should be seen as a seamless continuum, where the goal is not just recovery, but enhancing performance and reducing future injury risk.

Key Notes

Key takeaways

Bridge research ⇄ practice. Bart’s career sits at the intersection of applied research, teaching, and day-to-day clinical work—each informs the other so care stays both evidence-based and real-world.

Critical mindset ≠ cynicism. Don’t accept trends at face value; ask what’s grounded in evidence, what’s plausible, and where sound clinical reasoning must lead because research hasn’t caught up yet.

Rehab is a continuum. Think progression, not checkpoints: early foundations → gym capacity → field transfer → return to performance (not just pain-free function) with ongoing secondary prevention.

Ecological validity matters. Classic lab tests are useful early on, but you must evaluate and train in environments that resemble the sport’s chaos—especially for cutting/field sports.

Tech should inform, not dictate. Start with a clear clinical question, then use tools (force plates, IMUs, gait/running analytics) to quantify what the eye can’t see (forces, timings, asymmetries). The output guides training; it doesn’t replace coaching judgment.

Coach’s eye is trained, not innate. Learn the movement first (phases, mechanics), then review hundreds of reps, film, seek feedback, and pair kinematics (what you see) with kinetics (what you can’t).

Asymmetry is task- and metric-specific. There’s no universal “10% rule.” Tolerance depends on the variable, the task (single vs. double-limb), and the athlete’s sport/history.

Running is whole-body—and two-phase. Don’t fixate on stance only. Swing mechanics shape initial contact, ground-reaction vector, and downstream loading; trunk and arm action matter.

Load management + education are non-negotiable. Strength and mobility alone won’t solve overuse issues. Align training load, expectations, and clear goals from day one.

Biomechanics is one piece of a bigger puzzle. Lifestyle, stress, sleep, motivation, age, and context can outweigh mechanics for some athletes. Treat the person, not just the tissue.

Measure to motivate and plan. Baselines and end-goals make the journey visible. Use data to show potential (“can be improved”), set priorities, and keep athlete/parent/staff aligned.

Youth communication = performance language. For teenagers (and many pros), framing around jumping higher, accelerating faster, and playing better engages more than injury-risk talk alone.

Performance and risk. Technique cues that reduce risk but hurt speed/agility are a no-go. Aim for changes that protect and enhance performance.

Expect tough expectation resets. Second-opinion cases often arrive under-prepared but eager to return. Honest testing + transparent dialogue recalibrate timelines and buy-in.

Start with the end in mind. Whether non-op, pre-op, or post-op, program early choices around the athlete’s eventual sport demands (strength qualities, aerobic/anaerobic needs, reactive strength, agility).

Full Audio Transcript

Kurt (00:02.188)

All right. Good day, everybody. Today’s guest is someone who worked the intersection of cutting edge research and real world clinical practice. Dr. Bart Dinganen is a physiotherapist, researcher, educator, and trusted voice in the world of lower limb rehab, especially when it comes to ACL injuries and running related issues. Bart graduated from K11 with a master’s in rehab sciences and physiotherapy after.

Getting a lot of experience in the private practice, he went on to complete his PhD, focused on postural control and ACL injuries and chronic ankle instability. His postdoc work at KU Leuven and Hussle University published towards the field of injury assessment and rehab, particularly around ACL and running injuries. He’s published extensively in peer-reviewed and has presented on stages across Europe and beyond. Always with a strong drive to bridge research and clinical application.

Today, works with a wide range of athletes from recreational all the way up to elite performers, helping them stay active, recover smarter and return stronger. Bart, welcome to the Physio Insights podcast. We’re thrilled to you here.

Bart Dingenen (01:16.533)

Thank you Kurt for the invitation. It’s my pleasure.

Kurt (01:19.724)

Yeah, so us a bit about your background and what’s driving your mission towards what you’re doing today.

Bart Dingenen (01:25.552)

Well, I think it was already a good introduction, Kurt, giving some background of my professional activities. So, yeah, I’ve been working now since 2009 in the field, starting with a combination of research, teaching and clinical work in Leuven. As you mentioned, I did a PhD focusing on post-hoc control measurements in chronic ankle instability patients.

in ACL also a lot, but also from a preventive perspective, we did some studies. So in healthy athletes, non-injured athletes, and there’s a prospective work on that. But the main thing is actually through my journey, always combined research, teaching and clinical activities. I have to say since last year, it’s even more clinically focused. I…

left now the academic field. I’m so I mainly working now in my in our private practice motion to balance in Hank. As you say, I also consult there mainly in function of lower extremity injuries. So we try to work quite specialized in our clinical practice. So not everyone does everything. But my topic of interest is, as you mentioned, lower extremities, sports played injuries.

on different sports and different expertise levels of athletes. So yeah, that’s my activity. And next to my clinical work currently, I’m also mainly work as a consultant or giving courses around the world online, offline. Also again, in the fields of lower extremity, post-related injuries like

ACL, knee problems, agility wise. yeah, it’s a quite broad perspective that I’m working on, but I like it. I like the combination.

Kurt (03:36.332)

Yeah. And what is the most exciting thing about that combination? I mean, the research, the, and then the clinical work and, then maybe secondly to that, how do you, how do you combine it all and juggle it all together?

Bart Dingenen (03:46.574)

Yeah, the combination is quite difficult. I have to say I did it for more than 15 years. But as I mentioned, I left now the academic world. It was a very hard combination. Also a combination which is not always allowed by universities. But you know, as your clinical work grows and grows, it becomes even more difficult to combine it. So

So yeah, I decided to leave academics and mainly work clinically and provide them courses or consultancy for external parties. So yeah, it’s a difficult combination, but I think it’s definitely worthwhile to combine because it strengthens from different directions each other. both for my, if you can combine these different aspects, you…

get more insight in your clinical work. But also from a research perspective, you can put everything better in perspective, in my opinion, to have a better idea of what really matters in clinical practice, what’s really needed, how difficult real patients are in reality. Yeah, in this perspective, I think it’s a massive advantage to have the experience to combine these different factors.

Kurt (04:52.93)

Mm-hmm.

Kurt (05:16.034)

Yeah. And so if I understand correctly, you see that there’s a lot of translation that can go back into research by having that first-hand ground knowledge, working in the practice, seeing what needs are, what are the needs of the athletes and where the gaps are perhaps in the clinical practice.

Bart Dingenen (05:23.034)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (05:32.314)

Yeah.

Absolutely, I think clinical practice, you start to have questions, ideas, et cetera, if you can apply to the research, vis-a-versa, it’s definitely an added value. But again, it depends on the field of research you are in. My research was not really fundamental, it’s more applied. it also depends, of course, on what kind of research you do. But in my perspective, yeah, was, my basic idea was helping the patients as good as possible.

Kurt (05:55.98)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (06:03.824)

I’m quite passionate about that and that’s my starting point. For me, research was like a way to grow in that perspective from a theoretical point of view and I have better insights in my clinical work and still I’m reading quite a lot still. So I think that’s important to continue to grow clinically as well.

Kurt (06:08.067)

Yep.

Kurt (06:20.398)

Mm-hmm.

Kurt (06:31.66)

Yep. think from, don’t know how many years we know each other now, but I can remember even back in the days, I think we were having overlap in our PhDs, but I could see from the beginning that you have, since I met you, had that evidence-based critical thinking mindset, you know, not just accepting status quo, but pushing the boundaries, pushing the edge of what’s known and the knowledge in the field and having that one foot deep in research.

think really helps shape that thinking.

Bart Dingenen (07:03.332)

Yeah, it’s really needed, think, because a lot of things are going on in the field, especially these days. Everyone has a voice on social media, you know. And sometimes I think when you have less critical mindset, it’s difficult to distinguish what is really optimal or less optimal, what is really based on something. And it’s important to stay critical on everything we see and everything we do and to continue to grow every day.

Kurt (07:14.531)

Yeah.

Kurt (07:34.038)

Yeah. And how would you define a critical mindset?

Bart Dingenen (07:38.596)

Well, critical mindset is not shutting down, putting down everything that we hear, but just thinking, okay, is this idea really grounded, based on something? Or do we have some foundational evidence to support these ideas? And again, important to know is that not everything, if you were in clinical practice, not everything you do or can do can be based on clinical.

on research evidence. So I think the very good clinicians are ahead of research. So they base their interventions on what is known, but they also have ideas that maybe are not yet shown yet. So it’s again, in both directions doesn’t mean we can do whatever, anything we want, but it should be based on some fundamental ideas and then work on that building a clinical ID and then

hopefully in the future trying to prove these concepts in research. I think that’s the way to go and to move forward.

Kurt (08:46.038)

Yeah. Yeah. And how do you see your specific research that you did? How did you see that bridging the gap or kind of helping you in practice? Do you remember specific moments, moments or specific concepts that you thought, okay, what we’ve done in the research or what you’ve read in some of the research has really helped you become a better sports physical therapist.

Bart Dingenen (09:09.168)

First of all, we have to acknowledge that if you do research, you are only a very small piece of the puzzle. In the beginning, of course, when you do a PhD, you think you have done everything because you did so much work. But at the end, the more you know, the less you know, probably. And the more you know that that work you’ve been doing is only one piece of the puzzle. We should be very modest in that. That’s what I try to do. And because we need to see the big picture.

Kurt (09:22.092)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (09:39.374)

And once you see that bigger picture, you can have better insights. But once you think that the one thing you do is the thing, I think then you miss a lot. So that’s one point. But nevertheless, my work was mainly on sensory motor alterations after ankle instability and ACL, and also biomechanical alterations during changing from double extens to single extens.

than more dynamically jumping double-axe, single-axe, then into running. And next to running, more agility-based activities. Well, the basic understanding of these tasks and the alterations that you see or you read happening in the whole system can definitely help to better understand what’s going on after or before injury.

but also to have a better big picture view on the possible interventions.

Kurt (10:42.86)

Yep. It reminds me a lot. I remember one conference I went to and there was a presentation about, yeah, it was basically a symbolic circle. The circle was the volume of the circle was analogous to the knowledge that we know. But then the circumference was what we don’t know. And the analogy there was, yeah, as we expand the circle of knowledge, we learn, we understand, we can translate it to practice. But so does, of course, the circumference of what we don’t know. And it opens up more

sometimes more questions, more answers we have, the more questions, and the more offshoots and things, directions we can go.

Bart Dingenen (11:14.584)

Thank you.

Bart Dingenen (11:21.272)

Absolutely. the first point is to acknowledge that. And then trying to become better and better by more studies, by reading more, et cetera. there certainly a big field that we don’t know yet. Or maybe things that we thought we know maybe come into question after a few years.

So it’s an evolving, it’s interesting to see how things are evolving.

Kurt (11:53.006)

What is the biggest thing for you that has come back and you said, well, that’s things that we thought we believed, we did a certain way. Now the research is maybe showing the opposite or maybe we need to revisit what we initially thought and evolve to a new concept or paradigm.

Bart Dingenen (12:12.238)

Well, maybe the biggest evolvements have been, are taking now at the moment in motor learning. think we can describe lot of things that was what’s does a lot of time. We describe everything which is bad, which is different compared to normal. But then the question is, okay, what are you going to do about it? And then for example, if you see a muscle who is activated,

Kurt (12:32.705)

Yes.

Bart Dingenen (12:39.472)

or has a delay in activation, for example, okay, what are you going to do about it? When you look at the 90s, we talk, okay, we have to activate that muscle as much as we can, and then maybe we get some plasticity in our brain, and then your muscles get activated earlier. That’s a traditional approach. I think now we are further, and we are learning more how to learn patients to move and to…

to transfer really their rehab activities to the field. That’s a big question. Also, a question we have to be critical about. So what are we doing in clinical practice? Is that really transferring to the field? Transferring to, for example, cutting movement maneuvers in open environment, et cetera. So there are very…

were much more explicitly stating what athletes had to do in the past. think we move now much more to more ecological approaches where we start with the end of mind, meaning, okay, we have to go to the pitch. Is it running? Is it cutting? Is it whatever you do? And then trying to find better solutions to figure out what is more optimal for that individual? How can they learn?

How can we facilitate the learning process? And how can we dictate the learning process?

Kurt (14:09.868)

Yeah, I think that’s a very important distinction. And how do you how much how have you evolved your thinking of terms of ecological testing, as well as from not just from a from an exercise prescription perspective, but from an assessment or muscular, skeletal screening perspective?

Bart Dingenen (14:27.512)

Yeah, that’s a difficult one because we all think we have to do more ecological testing, so more real world environment testing. But the problem is with that idea is that your testing becomes also more variable. For example, if you start doing jumps with external objects or whatever you do in real world environments.

your moving outcome will also be more variable. So the question is, what is your interpretation of the test outcome? For running, think it’s little bit easier because the task is a little bit less variable compared to field sports, where we have continuously to adapt our tasks. And indeed, variables that we can use in the fields.

are of course available to have an idea what’s really happening when they go out in the real environment and to see what’s happening over there. So, Builds and Technology have definitely enrolled in that to be able to capture data in real world environments and probably we are moving further in that direction in the next couple of years.

Kurt (15:46.348)

Yeah, for the listeners out there that aren’t aware of what ecological validity or ecological testing is, would you mind clarifying how would you define that?

Bart Dingenen (15:55.684)

Well, to simplify the idea is that really that classically we did, we do tests and I don’t say it’s not valuable. We just say what we do classically is we do tests in a quite artificial environment. For example, we ask people to jump off a box and to jump as high as possible up without any distraction, without any relationship with the real world environment. Again,

If you have a very low capacity, for example, after orthopedic injury or surgery, these tests are, in my opinion, definitely valuable because we first need to build on the basics. But then the question is also, if the patient is passing all these tests, jumping or whatever you ask, is the wheel translating to the real world environment?

The question we stay then is then can we maybe improve that the validity of our tests by implementing aspects of the real world environment? And that’s big challenge, as I just mentioned.

Kurt (17:12.578)

Yeah, yeah. And what do you think is the biggest challenges of doing it in the real world specifically? I mean, how do you simulate as close to that real world as possible, depending on say the athlete in front of you and the profile in front of you?

Bart Dingenen (17:27.664)

Well, again, if you go to a few sports, come into much more chaotic situations. If you look at football or basketball, whatever, it’s continuously changing. So indeed, know there are studies now going on using inertial sensor packages, et cetera. However, we’re not yet there to apply that in real world, daily clinical practice.

Then I think, and that’s bad to say, our coaching eye also plays a big role there, which you need to develop, by the way, over the couple of years, and also to listen to the patients, how they experience it. For example, when a patient returns to on-field sports and they mention,

Kurt (18:16.589)

Yes.

Bart Dingenen (18:25.698)

It just feels like everything is moving so fast around me compared to the gym based exercises. And then you also see that the old neurological or neurocognitive factors come into play where the interaction with the environment is really important. And just talking to the patient, how they experience it, see how they react, are they going to freeze to reduce the degrees of freedom, et cetera, in these particular situations?

difficult, difficult to capture or to give one outcome measure there. I think there, yeah, our patient conversations and our coaching eye plays a big role there. Currently, currently.

Kurt (19:07.648)

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. And how would you say, how would you, what would you say to a physiotherapist that’s maybe starting off today and is wondering how can I improve my coaching eye? What should I look out for? And yeah, how can I learn to train the coach’s eye?

Bart Dingenen (19:25.232)

Yeah, very good question. The first thing is if you want to develop a good coaching eye for a certain movement is learning more about the movement at first. Because if you look at certain movements, you can also capture what you’re looking for. If you read something about overstriding and running, everyone is overstriding that the next couple of patients.

So you can also only capture what you know, what you’re looking for. So the first step is really to get into depth with learning that movement. And for example, running. Running is a really fundamental activity that we are not all, I’m not only talking about running when we talk about typically the recreational runners going out for a run, but also

Kurt (19:58.722)

Yes. Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (20:25.306)

field sports where running is a basic activity before we can go over to high intensity sprinting, acceleration, change direction, curved running. These are all derivatives of running at higher intensity. But again, you need to know some basic principles of these patterns, same for jumping.

It doesn’t make any sense if you start, for example, using false plates, if you don’t even know what kind of phases are going on in a certain jump or what a jump is really like from a biomechanical point of view. So it makes no sense to look at numbers then if you don’t know the task or to just look at with your coaching eye to have an indication of that pattern. So yeah, learning to move in itself.

And then you need practice, you need feedback, you need seeing hundreds, thousands of patients and film them and go around them. And this is something you develop not from today to tomorrow. And that’s reality, I think. It’s just like everything, you need also experience to get better in something.

Kurt (21:46.35)

Yes, absolutely. And what I also tend to see is I remember when I was doing my internship in physical therapy as well. yeah, the caseload was one after the next. And for me, was during my internship, was mostly rugby players and also ACL and doing isokinetic testing. And I remember, I think it was only after the first few hundred where I started to really, yeah, sort of put together a bit of a…

Bart Dingenen (21:55.79)

Yeah.

Kurt (22:11.382)

identify the patterns and identify the movement and then see what is really important going on to the field and how, just for example, the testing itself didn’t always translate the results that we were finding, didn’t translate to what was happening on the field. Sometimes we would find, you know, very good balances or return to play criteria seemed great, but the moment they were on the field, you could see that the athlete was nowhere near there. But that’s only after many cases that you start to kind of develop a

a different new sense of trained understanding. And I think what, especially in the day and age, I mean, we’re obviously building technology to help for clinical therapists, but I think there’s a fundamental step in understanding and, and yeah, having developed that coach’s eye, that if they miss that and they jump too quickly onto using technologies, that they might miss out on that clinical reasoning experience that’s vital to their, yeah, to their development and growth as a physical therapist.

Bart Dingenen (23:11.504)

Absolutely, I can’t agree more. That’s a question I often get. So they want, they see, for example, me using some technology and then they ask, where can I get, what should I measure? Okay, then my question is, what do you want to measure? What is your question you have? Because first you need a question and then you need maybe a system that can assist you in your clinical reasoning. That’s not the opposite way around it you have to work on.

So you first start with the idea, with the question, based on your understanding of the movement. And then technology might help you, might inform you, not dictate you, might inform you to make clinical decisions. But it starts with the basic knowledge of whatever task you look at.

Kurt (23:59.82)

Yeah, yeah. And how, what recommended recommendation would you give to the physiotherapists that are thinking about using technology without having maybe, without knowing what question they want to really ask from the technology or question they want to ask that will help them all use, want to use the technology in a way that can support them, not make them completely dependent on it or be, feel like they’re being replaced by it.

Bart Dingenen (24:27.642)

what my advice would be then.

Kurt (24:30.733)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (24:33.752)

Yeah, as I said, I think first studying the movement itself and reading a lot about the movement, some basic biomechanics, you look at biomechanical parameters at least. Yeah, and then maybe then by time and not to, by time to develop a question that you have and not immediately to jump on everything you see and to be very fancy in your…

Kurt (24:39.107)

Mm-hmm.

Bart Dingenen (25:03.812)

in your approach, but at the end, maybe overshooting or whatever thing you have. So, I think a lot of approaches are really overshooting and trying to measure everything. But at the end, the clinical interpretation then is the question. You can have the best measurements tool you want. You can also have the best program you want, but at the end, it’s

Kurt (25:08.813)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (25:31.244)

Just measuring patients doesn’t make the patient better. It’s what you do with the measurement, how your interpretation is of the measurement. What the implication is towards training. Training makes the patient better. Testing can help to develop your training. But just doing a good report and saying this, this, this, this, this is what the report says doesn’t tell you anything actually. It’s a translation to the training.

that is important.

Kurt (26:05.12)

Yes, I couldn’t agree more. Couldn’t agree more. what I mean, any other physiotherapist that they can see you working in practice, doing you do adopt a lot of technology. So where do you feel that you say, okay, I wanted to try out new technologies, test out new technologies? Where does that where do the puzzle pieces then fit in nicely for you in terms of, you know, at what what point do you say

I want to bring in this technology, I want to try it and I want to use it for this specific case or this specific population.

Bart Dingenen (26:37.68)

I’m always mainly looking for technology then for things to objectify that are difficult with my own coaching eye. So things that I miss with my coaching eye or cannot see, for example, forces, you cannot see forces. What you can see is kinematics, which angles, which combination of angles people are moving. I’ll come back to that. But kinetics are forces acting on our body.

And for example with inertial sensors, with force blades, we can have certain IDs on system forces. Doesn’t mean structure-specific forces, but really on the forces acting on the system. So that’s something you cannot do with your naked eye. We have to be very neutral on that. You cannot see forces, so that’s for me an added value.

The first question is what is the added value compared to what I have? If it’s no added value for me, it’s a no-go. If it’s added value that is useful in a clinical practice, yes, can be helpful to again to assist your clinical reasoning.

Kurt (27:44.11)

Mm-hmm.

Kurt (27:56.182)

Yes, as a supportive aid or something to help. Yeah. Or do you ever find that there’s cases where it challenges your clinical reasoning in a sense where you thought one thing and it showed the opposite to maybe what you were thinking?

Bart Dingenen (28:12.336)

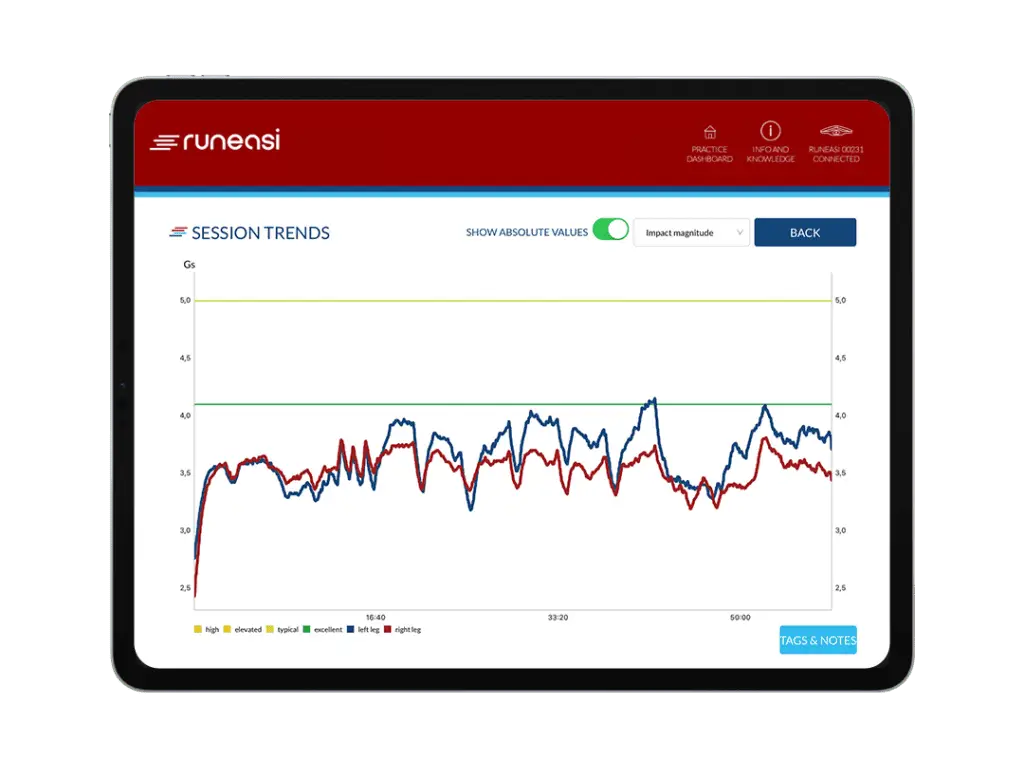

Yes, especially when you focus, for example, on running on asymmetries that you were not expecting to see in terms of impact loading, terms of ground contact times, which are difficult to capture with the naked eye. Same for jump testing. If you think they look with your naked eye quite well, but then when you put them on the…

on the force plate and you see still some asymmetric work around the limbs or some slower contact times or whatever, your lower reactive strength, etc. Just to name a few. Again, it’s then sometimes they challenge you more because it’s more difficult to reach the full potential because previously when you didn’t do these measurements or

Kurt (28:58.222)

Bart Dingenen (29:10.128)

had when you had less possibilities to measure it. It was your naked eye or your general feeling that would dictate whether they are right on track or not. So now it’s challenging yourself and the patient more, leading to better training, longer training. and then therefore also in my perspective, better outcomes.

Kurt (29:37.696)

Absolutely. And when you see the concept or when you discuss the concept of symmetry or asymmetry, do you have anything that guides your thinking in terms of, you know, benchmarks or things that, you yeah, how do you define

Bart Dingenen (29:49.008)

Very, uh, a very good, good question. Also a difficult question. Um, I think for those who are interested in that, Chris Bishop recently wrote a very important paper on that. Um, can share it maybe afterwards. Um, cause asymmetry really depends on the outcome you measure. If you take, for example, the classic 10%, okay, that’s very general. But if you have some outcome, which is more variable.

Kurt (30:01.622)

Yes.

Bart Dingenen (30:19.694)

The 10 % may be not enough or for another variable might be too much. So it will depends on the variable you’re measuring how much you can expect from a normal population. And again,

A lot of our patients and even athletes are by definition not symmetrical, based on the sports, based on the activities. And then sometimes it depends on which limp you get to injure or in the previous history, what you can expect to be symmetrical. So yeah, you always have to be very careful, I think, on what to do and how to interpret these asymmetries.

For example, do you test a double leg activity? Do you test a single limb activity? By definition, if you do a double leg activity, one leg is dependent on the other limb. So it’s really depend on the task, on the person, on the outcome measure itself, what you can expect. And it’s not possible to give one answer on digitity percentage of asymmetry you could expect.

for all the outcome measures you could measure in clinical practice.

Kurt (31:44.236)

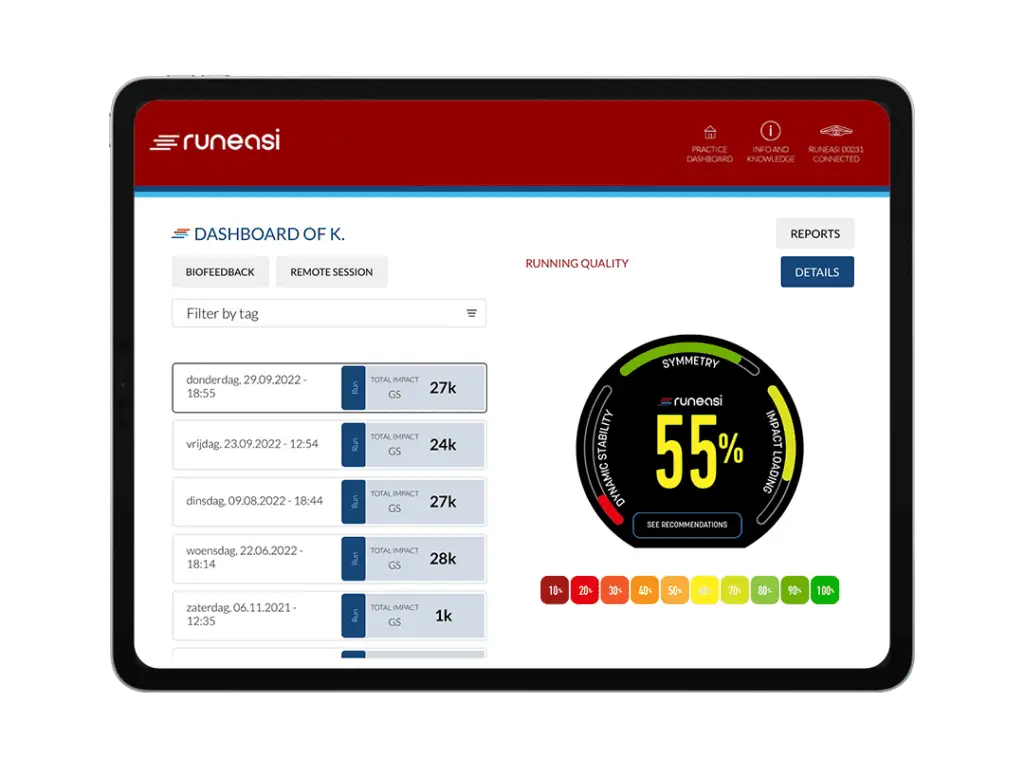

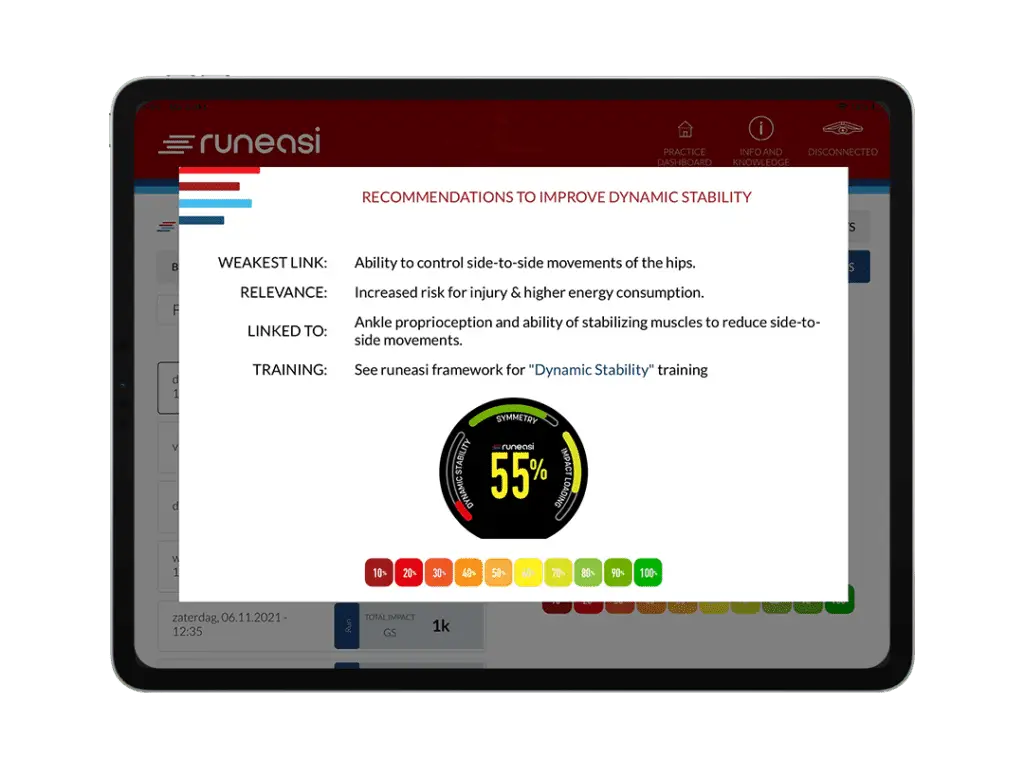

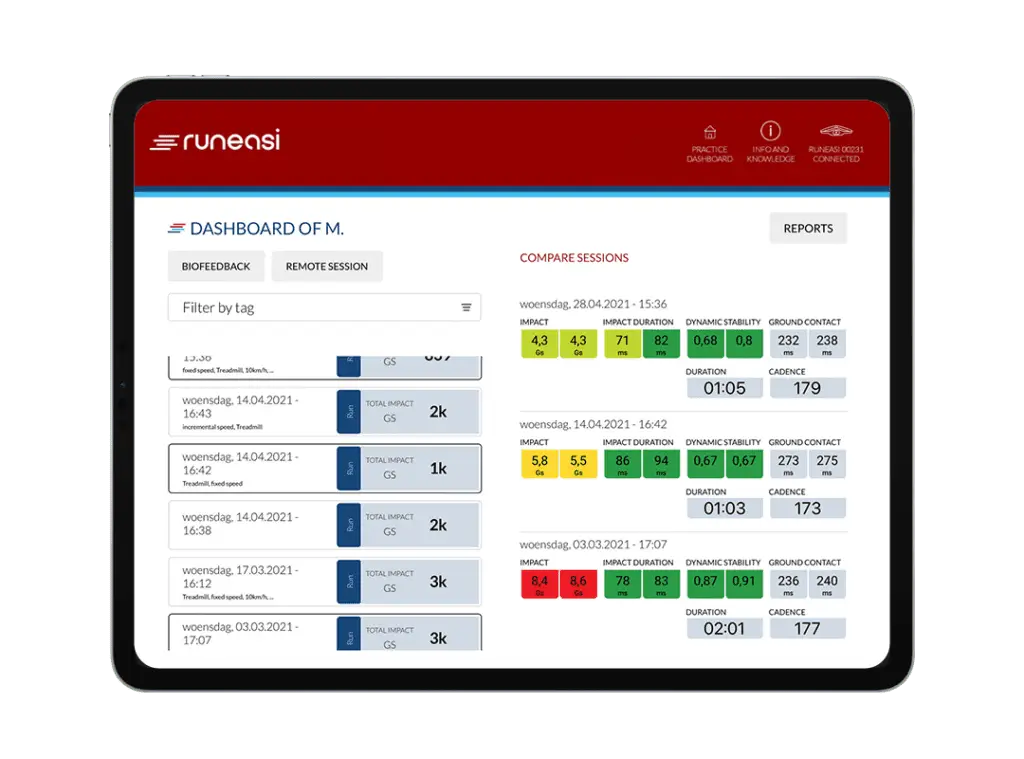

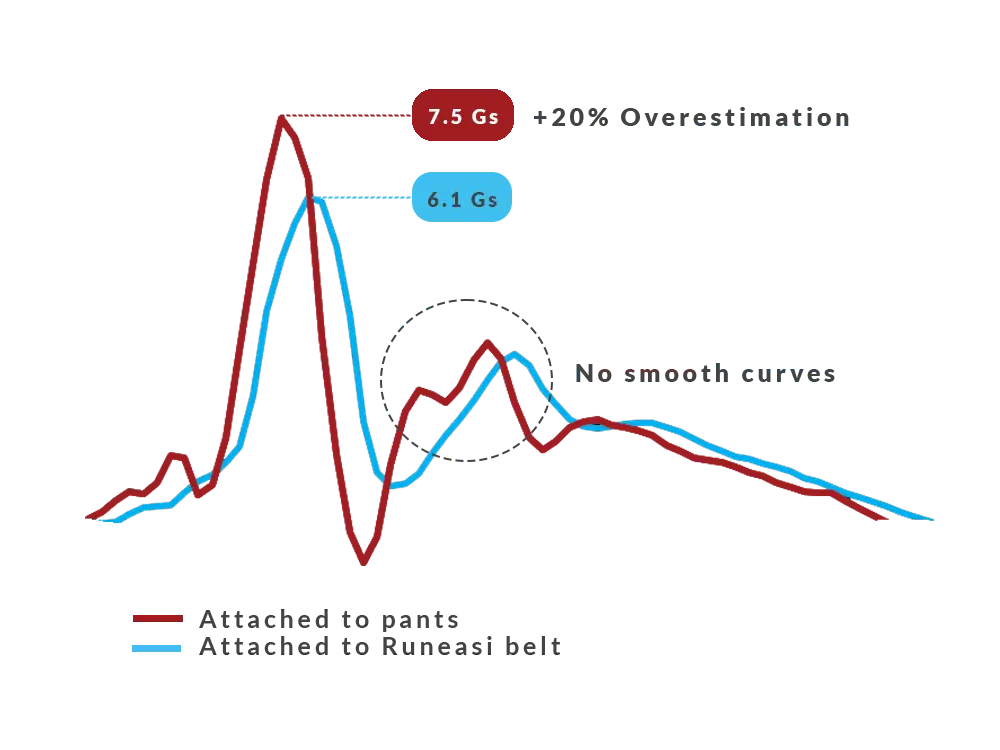

Yeah, I can relate to that. when we were, for example, creating the benchmarks for RunEasy as well for the different kinetic measurements, we noticed that every parameter or metric had its own sensitivity and its own bell curve of population norms. And if we were to use all at the same, say, 10 % rule, we would have some that are really overly sensitive and some that were not sensitive enough. yeah, so for us,

Bart Dingenen (31:56.11)

Yes.

Kurt (32:12.534)

Our thinking there was to try and at least quantify as much of the healthy population to see, for each metric, maybe each one has its own specific data benchmarks. But even there, we know that specific populations, specific injuries, we were talking about overuse injuries in runners versus ACL reconstruction and return to sports requires more nuances and there’s caveats, of course, in different scenarios.

Bart Dingenen (32:42.48)

Yeah, sorry.

I don’t hear you anymore.

Kurt (33:13.156)

Yeah, yeah, from what we saw from our benchmarks, I think there you have to be metric specific to what you see and how you defined, you know, especially the criteria for cutoffs. And I wanted to ask you, what are the nuances between, looking at asymmetry or overloading versus offloading in an ACL patient versus, say, a runner with an overuse injury?

Bart Dingenen (33:47.184)

Your noise was a little bit… I don’t know what’s…

I have the connection, I know.

Kurt (34:03.184)

right, we’re back on air. Can you hear? Is it okay? is it? What would you say is maybe one of the big misconceptions when it comes to running rehabilitation?

Bart Dingenen (34:09.658)

this.

Bart Dingenen (34:17.488)

Maybe one of the big misconceptions is missing the big picture. So that means that we focus on one certain aspect, but maybe we don’t focus enough on other aspects which are also relevant for that person. So that multifactorial clinical reasoning is really important. Depends on the type of injury, of course.

If you have bone stress injury, you might focus on different aspects which were relevant for that kind of injury. If you have a tendon issue, it might be different things. Typically, to give an example on that, we also see that people focus on strength, mobility, et cetera, but maybe forget training load. So it makes not so much sense to do some exercises, but then not to advise them.

on what they’re actually doing for running. So that’s a very typical misunderstanding, think, or something we miss in our approach that we just do some exercises, but we forget to do some clear education on what’s needed and also to have a good load management program or intervention to try to get them on track again.

Maybe another one could be that often we try to focus on the or to try to find the injured tissue or to identify the tissue that’s injured. But maybe for some injuries, that’s maybe the wrong question. Maybe we should identify more why is that zone or body zone painful and maybe not to just to say, okay, this is this or this or this.

tendon or fascia or whatever, which is the source of injury for especially for some regions like the groin or the hip or even with more nonspecific knee pain. It’s sometimes very difficult or to particularly or even impossible to really identify the source from a structural point of view of the pain. And then

Bart Dingenen (36:42.212)

That also leads to practices where clinicians try to fix the injured tissue. But in essence, they forget about the contributing factors on why that zone of the body might get painful or whatever the symptoms might be for the athletes. And I think that’s one of the big misconceptions.

Kurt (37:10.883)

Yeah, yeah. And where do you see compensation patterns playing a role?

Bart Dingenen (37:17.668)

Well, especially when there’s a lot of pain, yeah, a body is always smart. A body typically doesn’t want to have pain and try to move or away from the pain. be, be, can be in a sense two things or between limbs. So interlimb compensations, or can be within the limb to shift the load.

from the injured body part towards a higher or lower adjacent body part. So these are typical the effects we see. Yeah, compensations, mainly if there’s a lot of pain, otherwise it’s difficult to call it a compensation. Maybe it’s just a pattern, which is maybe less optimal for that body part in terms of loading.

Kurt (38:16.579)

Yeah. And is there something specifically that you see like recurring a lot of the very common patterns to say, pick an injury of your choice and say, would you say is often, things that recur at your office?

Bart Dingenen (38:29.626)

Yeah, we did also some studies on that when we focus on running and because my basic idea was or is when you look at the terrestrial studies, they focus on injured versus non injured and they say, okay, those with patella femoral pain or those with tibial stress or whatever move like this and those who are not injured move like that. But even

When you have a certain body region which is painful, you can have different subgroups or patterns or presentations that you miss then by putting everything together. That’s some of the problems in biomechanics. you just look at the group, one group versus the other, you miss a lot of subtleties and then the conclusion is it’s no different, so biomechanics doesn’t matter.

which might be not always the right conclusion. I don’t say that biomechanics always matter. That’s not what I’m saying, but I’m saying when they matter, it’s a matter of identifying and thinking about what kind of loading is going where in the system. For example, if you have patients with a big, try a lot of dorsiflexion at initial contact.

we have identified that pattern might be related with, biomechanical pattern that’s related to anterior, tbl stress or complaints, example. all the way around, if you look at mid stance, are people lose their ankle stiffness, go into very deep, ankle dorsiflexion, a lot of, knee flexion.

a lot of pelvic drop that system stiffness that they typically are lacking that might be related to again more post-traumatial chin problems might be related to ankle knee pain might be related to lateral hip problems so it depends on where the painful side is or what might be relevant presentation there but what we’re looking for is typically

Bart Dingenen (40:50.256)

what we call passive attractors. So tendencies where people tend to go and typically it’s more passive strategy. For example, as I give you the example here of the lack of ankle stiffness falling in the deep dorsiflexion whereby the ankle has no ability to control upwards the kinetic chain anymore and to dissipate the energy. that’s

typical pattern we see but again you can go we can talk a lot about that it really depends on a lot of factors

Kurt (41:28.891)

May I ask what drew you to biomechanics? Where was the curiosity and what is it that drives you to use biomechanics in your clinical research?

Bart Dingenen (41:35.022)

Yeah. Well…

Again, to be clear, I’m not a pure biomechanist, I’m just a clinician who has a definite interest in human movement. So I think when you work with human movement, whether you are a physical trainer or a physical therapist, whatever you do, I think it’s our job to have good understanding of that movement. And then when you study movement, you are…

we are typically going into biomechanics. But again, clinically, even if you, it doesn’t matter if you’ve done studies or whatever you do from a biomechanical point of view, clinically, biomechanics are only one piece of the puzzle. And that’s when we go back to your previous question on the multifactorial clinical reasoning. It’s not only biomechanics. Typically, if we forget about general health, behavioral aspects, lifestyle factors.

etc. All these factors come into play and for some patients biomechanics is one of the key aspects. Maybe for some who have made some training errors, who have no sleep or excessive stress in their life etc. Well, maybe biomechanics doesn’t matter at all. So it depends. But biomechanics took my interest because of

My interest is to learn more about the human body in movement. That’s what I applied in my studies, later on in teaching also. I developed a sports biomechanics curriculum, for example at university, etc.

Kurt (43:21.763)

Yeah. And to think about it one step further, what inspired you then to become a teacher or to give courses to other physical therapists?

Bart Dingenen (43:30.732)

it’s not that I said, okay, tomorrow I wake up and I’m to teach courses. That doesn’t work like that. It’s developed by time over the years and years. just, I know, got more and more questions on doing this. It’s just not that I’m asking that for the dude. It’s just developed by time. And what I like about teaching is that, especially when

people are working already. teaching for physical therapists who graduated already is that they have really the questions on what to do, how to do, how to implement clinical reasoning and research into practice. That’s different compared to teaching at the university where students typically just want to pass the exam. And they don’t have yet that clinical question to treat the patient.

They think more about how can I pass the exam. So that they maybe don’t see yet the application logically because they need to see the patients in the future. So, but I, when I can help people to get, have better insight in these problems, for example, when I teach a course and I got email, like, okay, after the course, I got more insight. I was able to apply this with this and this patient.

I’m more than happy. I have been able to assist other clinicians in their work or to find a better structure and that’s for me very rewarding.

Kurt (45:11.343)

Yeah. And what got you to focus specifically, I you give courses on ACL rehabilitation. What made you focus on that and inspired you to do, actually specialize in ACL rehab?

Bart Dingenen (45:26.498)

Also here, was not like… It partially was a choice, but also that developed by time. Because when it started doing research, it was focused on the ankle, ankle instability. But at that time, I saw a lot of parallels in the sense of remotest alterations between ankle instability and ACL. And then I went to my promoter, Professor Stas, and I said, look, it might be…

very interested to apply these same measurements as well in ACL patients. Yeah, and then we, it moved on, it moved on, it moved on. And yeah, finally, because I combined my research and clinical practice and I began to see more and more of them, yeah, it became more like, you can call it specialty. I don’t call it specialty, but.

It’s more like a particular interest in that field. And as time went on, as I mentioned, there became a higher and higher demand to teach these courses based on the positive feedback I got.

Bart Dingenen (46:43.632)

And also I think the knee is really interesting for me because it’s really in the lower extremity, in the intermediate joint where you need to understand the whole spectrum and if you want to understand knee problems better. So it’s really like in the intermediate joint which is for me very interesting. But yeah, doesn’t mean that the foot or the hip are not…

It’s not interesting at all, but just my work is more known in the ACL. in clinic, I see typically not only knee problems.

Kurt (47:24.377)

Absolutely. Would you like to touch a bit more on what you mentioned there about a spectrum of rehabilitation?

Bart Dingenen (47:36.332)

What do you mean for a spectrum of rehabilitation when you work with patients with different problems?

Kurt (47:42.267)

Yeah, or how do you view it as a spectrum or in terms of defining return to play criteria and rather than having a one-off yes-no decision, how would you compare that to looking at it through a spectrum view?

Bart Dingenen (47:49.369)

Okay, yeah.

Bart Dingenen (47:56.624)

Aspective view means that you see rehab more as a continuum and not like we do some tests and we do some activities and then it’s finished. We see that continuum based approach as a step by step overlapping, gradual progression throughout time where we try to be data informed.

about their decisions and clinically informed. But it’s a spectrum in this case, we want to try to be as fluent as possible in the progression across different steps. Once you get too abrupt in your progressions, the risk to develop problems is higher. So that’s also…

clinical experience you need to find really that subtleties in your progressions to be very progressive in your continuum. And also the continuum at the end that means that it’s not enough to restore or reduce pain or restore function but the basic ideas to especially in athletes is to improve performance.

That’s a big challenge. So we want to improve performance, but at same time, reduce injury risk. In the past, the classical view of physical therapy was we reduce pain, improve range of motion, improve strength, and then we restore them, hopefully to the same level as before, but typically it’s lower still, if you look at literature. But the challenges for the future physical therapist is that you

improve performance and you reduce the risk because there was probably a reason why they get that injury at first place when it’s a non-contact injury, etc. So you want them to get better as before and that journey starts the first day they move in your practice. Even if it’s pre-operative rehab, if it’s non-operative rehab, post-operative rehab.

Bart Dingenen (50:16.432)

It’s a continuum and you need to start with an end in your mind to be able to make a good program from the early days on. knowing what you’re preparing for is very important. From a mobility perspective, from a strength perspective, is it endurance? Is it maximum strength? Is it reactive strength? The whole spectrum there. From a physiological perspective, what is the aerobic capacity? And aerobic capacity.

whole spectrum there. And then you can define profiles of the athletes across time in direction of your end goal. And the end goal is still then that they do secondary prevention after returning to sports, especially when we talk about massive serious injuries like orthopedic surgery, etc. So that’s all continued.

Kurt (51:08.921)

Yeah, yeah. And is there something is a specific case that that that you would like to discuss that, you know, that highlights that continuum or that end goal of being able to juggle? Yeah, the return to performance versus Yeah, the injury prevention side of

Bart Dingenen (51:23.844)

Well, examples. Yeah, typically when you treat them well from the early days on, and when you also have free adaptive data, what we see these days is that, for example, when you look at, just take one example, the jump data, that they outperform themselves compared to the pre-injury data, and they just become better athletes, faster, stronger, higher jumpers, faster acceleration.

Et cetera. So when you have data, okay, you can try to improve it, but also they mentioned it typically by themselves. But that’s only the case when they are very compliant with the program, when they’re motivated, when you are really sticking to it, to the plan, make a good plan together. And that doesn’t happen at all. It doesn’t happen at all with the patients who then go on holiday, then this, then that, you know.

It’s a big challenge to have better performance after injury during rehabilitation. So it takes a massive work from both the athlete and the therapist to go there. So yeah, that’s one example. Another example might be that you also need to implement the things you do inside in the gym.

to on-field rehabilitation. And that’s also recognized more and more that we come back now to the ecological validity of our rehabilitation. It doesn’t make sense to only do some anticipated gyms in the gym and then think they can go to an anticipated cutting in real world environments. So we need to transfer that also and to make gradual progression from the gym to the field for field sports.

That’s not an example.

Kurt (53:23.291)

Do you ever get a case or situation where you get a referral from a football player comes to you and they’ve seen a doctor or physio and you’re concerned as the status that they’re in or that they haven’t maybe done a full rehabilitation or that the expectations from the player or the athletes are completely out of whack or out of proportion?

Bart Dingenen (53:49.904)

Definitely. I see a lot of second opinions or third or fourth opinions. Patients who have been in so-called we app for months or for years sometimes, but still are lacking some basic criteria to really even go to running, for example. But at the same time, they expect because it’s so long after, for example, operation or start of the pain, whatever the problem is.

that they still expect to be very quickly back on the pitch because it just by time it’s so long. So that’s a big challenge then because you have one, you have the expectation of the patient. At the other hand, you have the reality check where you do some measurements, you do some evaluations and you see there is still a lot of work to do before you can safely return or progress. So then you need to have a good conversation.

And to be very clear in your approach and in your assessment, there an assessment can also sometimes help to visualize what’s not yet optimal. Because maybe you don’t know it. And if I don’t know it and they think, I’m so many months after injury, then I expect to return. But when they see their, just to give an example, their jumping height is, or their quad strength is still 50%.

But yeah, it has never been measured before. And when you do now with the measurement and you confront them with the reality, then okay, I have some work to do. But mentally, that’s sometimes hard because there are so long already losing time. And then you need to start another journey. So that needs a good conversation first.

Kurt (55:36.667)

Mm-hmm.

Kurt (55:47.599)

Yeah, I can imagine the conversation, can be sometimes, yeah, tough conversations to have, but really important ones to manage expectations.

Bart Dingenen (55:55.108)

Yeah, that’s really important. my advice also, especially when, not only with very massively strenuous orthopedic surgeries and injuries, but also with obvious injuries from the early days on to really have a good conversation on what is the injury, what they can expect, what they can do about it, what is realistic, what should be their expectations, et cetera. Otherwise,

you lose each other throughout that journey. You want to do something, but at the same time the patient expects something different. So they get frustrated, they get disappointed because they do something they didn’t expect or it just doesn’t match. So if you can, from the really early days on, make clear expectations and realistic goals, I think that’s really important to not lose each other throughout that journey.

Kurt (56:55.652)

Absolutely. think that’s really, yeah, it’s really critical to be able to, like you say, keep on that journey together, manage the expectations. it seems like also use technology plays a role there and being able to kind of give an extra perspective, extra puzzle piece that not to give them a shock factor, but to give them an awareness. Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (57:17.38)

Yeah, and the goal is always, that’s what I also say, it’s not to say this and this and this and this is bad. No, just say this can be improved. It’s not a way of thinking, positive way of thinking. What happens, happens, you know, this is the current status. This is the new starting point that we use to work towards an end goal. And the next steps are just steps in between. But if you don’t have a baseline,

Kurt (57:29.22)

Yeah.

Kurt (57:33.423)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (57:44.72)

And you don’t have an end goal. How can you expect that you can manage the journey in rehabilitation? That’s a big mistake we often make. We don’t measure how or don’t have an evaluation or assessment what is currently going on. And we might lack the real end goals or real ways to go. So then it’s very…

Also for the patient itself, very difficult to be motivated and to set goals, etc. And for the therapist, it’s difficult then to make a clear pathway. So therefore, again, doing a good assessment can help also from a motivational point of view. But not, as I said, to break down the athlete and say, this and this is negative. It should be a positive improvement aspect, not…

Kurt (58:34.031)

Yes.

Bart Dingenen (58:41.2)

just to line up everything which is bad.

Kurt (58:44.252)

Yeah, I can imagine, you know, especially if you’re showing them data that there’s a red, you know, the data shows that they’re in the red zone, or they’re very, very low, very poor, that if it’s not communicated in a sense, like you just mentioned, after you put it really brilliantly in it, know, to show them that there’s potential to improve, and not name and shame and say, well, look, this is so bad that in essence, you’re so bad that there’s just no hope, you know, you don’t want them to give up and say, well, what’s the point? If I’m so

Bart Dingenen (59:05.807)

No.

Kurt (59:13.147)

If the gap is so far to close, how do you motivate?

Bart Dingenen (59:16.976)

It depends on the context, how the patient presents. If they present with such a strong idea that they have to return tomorrow, sometimes you have to be more strict in your language and saying it’s not safe. So it depends on the presentation of the patient and the expectations in the first place, also the age and the intellectual level of the patient.

Kurt (59:31.845)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (59:46.52)

what you can explain, what you cannot say. But it’s really important to be open in your communication and to be honest and clear about expectations and goals to be in there together.

Kurt (59:46.693)

Yeah.

Kurt (59:58.213)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, and I was just about to ask you, how do you, you just touched on age. How do you tailor your conversations to the youth players, the younger ones that, yeah, of course they have a lot of aspiration, right?

Bart Dingenen (01:00:13.454)

Yeah, Definitely, I think that’s a very important population, which I also see quite a lot, is with the teenagers. The difficult thing is there, okay, how do you explain something? It should be as simplified as possible in the first place. But also you have another party, which are the parents, which are often very, very close, especially in athletes or trainers or even managers.

Kurt (01:00:35.676)

Thank

Bart Dingenen (01:00:42.21)

Yes, and some sports. So you should be very clear in that not to make it too complicated and talk language they understand. That means also in terms of not only talking about the negative side of injuries, but more in function of performance. Because that’s what they’re interested in. They want to be faster. They want to be higher jumpers. They want to be

Better performance, that’s what the interest of especially kids is. They want to be better than their friends and they want to become the best professional player ever, of course. But then it’s important from a motivational perspective also to talk in that language, which is understandable and that gives much more motivation.

Instead of you are saying that this is bad and this is injury injury injury. But when they have never had an injury, it’s very far from their ideas. It’s they’re just want to play the sports as good as possible. And your intervention should assist that if it doesn’t assist performance, but it might reduce injury risk. You’re not in the right track. And that’s what we often do. We say you need to go.

into more flexion, softer landings, shorter distance from your support to your center of mass, example, inside cutting. But if it reduces performance or changes your action speed, it makes no sense. It’s even for me a no-go. So you really should target these aspects, which are both performance…

improvements, aspects that improve performance, but also then think about injury risk and technique, which can be helpful there.

Kurt (01:02:52.284)

Yeah, I can relate to that as well. Often we see depending on the continuum and whether you’re trying to optimize for the goal of performance or for injury prevention, take impact loading, for example, while you’re running. If it’s from an injury prevention aspect, you want to minimize the load and reduce the external load on the body. But at same time, you need them to be able to land with a stiff leg and then be able to absorb the impact while

Bart Dingenen (01:03:18.223)

Yes.

Kurt (01:03:19.105)

so it’s you know it’s counter it’s yeah the opposing goals right

Bart Dingenen (01:03:22.946)

That’s a very good example of let’s say impact loading during running. That’s maybe a good example of if you focus just on your outcomes of your assessment of your technology and you say, really, look impact magnitude is the factor I’m looking at. For some injuries, it might be relevant. But for some, the problem is maybe that they just have too low impacts, as you mentioned.

Maybe they go just very fluffy into very deep flexion, very deep dorsal flexion and they have very low loading.

Kurt (01:03:52.89)

Yeah.

Kurt (01:04:00.333)

Overly compliant.

Bart Dingenen (01:04:01.87)

But yes, but then when you look at your data and you see, they have really, really nice impacts. So that’s good, but that’s not the reality then. That’s the problem if you have a quite limited view on a certain biomechanical outcome and just look at one or a few factors and then forgetting about the whole big picture. So that’s important and that often happens.

Kurt (01:04:24.538)

Yes.

Bart Dingenen (01:04:30.458)

Because they look at the report and it says it’s green and it’s good and then therefore your running is good and I don’t see an outcome. yeah, that’s think far too simplistic. And to go further into running, know running, I think we see running, I see running as a single limp landing activity, but it’s a whole body activity. We forget about that.

Kurt (01:04:45.444)

You know.

Bart Dingenen (01:05:00.784)

For example, we typically focus on the stance phase, but not so many people focus also on the swing phase. The swing phase will dictate what will happen at the initial contact. So the orientation of your ground reaction force, for example, will define what happens just before you catch the ground. But when you only take your limited view on that stance, on the mid stance or on one of its heel mid foot, forefoot landing,

Kurt (01:05:14.509)

Absolutely,

Bart Dingenen (01:05:31.108)

Yeah, that might be less relevant then when you don’t see the big picture. When you don’t look at the system motion, when you don’t look at the trunk, when you don’t look at the arm motion, when you don’t look at the swing phase, you lose the whole pattern or you forget about the whole pattern. And then especially when you go to look at one pattern of limp in the stance phase without taking the whole picture into account.

then I think it’s sometimes dangerous to make strong conclusions. So you should be aware of what is the system measuring, what is it not, and what do I need to have a big picture of the movement that you’re assessing.

Kurt (01:06:12.207)

Yeah.

Kurt (01:06:15.631)

Yeah, and it ties in what you saying earlier about the coach’s eye or the trained eye, that there’s also an element, there’s obviously the element of the output of the kinetics perspective of the biomechanics, but then you have the kinematics and you have the visual inspection and what you can, yeah, the qualitative assessment is equally important, right? And to combine the two of them and the last thing we want is a user of technology to just only be stuck with their face in the iPad.

and not looking at the patient in front of them, right?

Bart Dingenen (01:06:44.804)

That’s real.

Yeah, that’s reality. Same in false plates, you should focus so much because it’s very interesting. You focus so much on the numbers and then you didn’t see it. Yeah. Yeah, that’s

Kurt (01:06:57.564)

I didn’t

Bart Dingenen (01:07:02.64)

Not the goal, no. But yeah, important to have big, again, we come back to that, points, a big picture view of your patients when you’re doing assessments.

Kurt (01:07:15.769)

Yeah, yeah. so it’s also I guess it’s a skill to go to the big picture, but then very quickly be able to go to drill down into the into what’s relevant at the same time.

Bart Dingenen (01:07:23.056)

yeah. That’s absolutely the way you need to master it. It’s a complex issue. But then I think the mastery comes from simplifying the complex stuff for yourself, but also for the patient to really try to identify the aspects that are most relevant.

And then to build that into a program which transfers, which really targets the overall principles and not just one angle or one force, whatever. So that’s really important. Bringing it all together. Therefore you need clinical experience, need good understanding of the movement, as I mentioned.

But to simplify it without making it too simple is the big challenge.

Kurt (01:08:33.136)

Yeah, yeah, what we often see as well as, you know, bringing clinical reasoning then to the to the next stage, which is like, you have biofeedback real time.

can be a huge step where intuitively it sounds like if you have biofeedback or if you have data, real-time data, you can understand what’s going on, you can build a picture. But we also realize that that literally means clinical reasoning needs to be done in real time. Where do you focus your attention? Where do you ask your patient to focus their attention? What cues do you give? I think there there’s a whole unexplored realm of opportunity, but at same time, complexity,

Bart Dingenen (01:09:05.167)

Yeah.

Kurt (01:09:12.381)

at the next order of magnitude.

Bart Dingenen (01:09:15.598)

Yeah, but again, we have to realize it’s complex, but then we have to make choices and set priorities, stick to the priorities, make a plan and work towards an end goal. That’s a little bit, you could plan your re-app activity, but indeed it’s not so easy because you have to take into account a lot of factors, which are often far more than biomechanics.

what makes it even more complex. All the situation around a person. It’s a person with injury, not an injury.

Kurt (01:09:45.337)

Yeah.

Kurt (01:09:55.001)

Yes, I think sometimes we can get so focused on the injury or what the pathology is and trying to fix that itself without zooming out, not only metaphorically, but just looking at the big picture and looking at the whole kinetic chain. We often say that if you see an injury distally, what’s going up the kinetic chain? Is it top down, bottom up? Where are the weakest links? Where is it coming from?

Bart Dingenen (01:10:06.382)

Yeah.

Bart Dingenen (01:10:10.021)

Yeah.

Kurt (01:10:22.075)

And it’s never presented with a straightforward, very seldomly I find presented with a straightforward case where you have immediately all the answers. It requires a solid process or like a structure, like you say, and good questioning and good investigation.

Bart Dingenen (01:10:35.822)

Thank

Bart Dingenen (01:10:41.264)

Yeah, absolutely. And it starts with listening to the whole story of the patient. Patriot language, clarification, simplicity in your language. Yeah, listen first and then load wisely, would say. But that’s the essence of the story at the end.

Kurt (01:11:04.345)

Yeah. Yeah, yeah, absolutely. Well Bart, I really appreciate you sharing all your insights. Yeah, we’ve covered lots of topics, we’ve gone around in different loops, I would say, gone from clinical reasoning to how do we merge research and translate the research into practice and how do we inspire the other way around as well.

what we see in the clinic to make better research so we can keep pushing the science further and forward. yeah, clearly you’re doing that. And I think keep doing what you’re doing. We love the fact that how you keep translating the research into practice, how you keep moving the, yeah, moving the clinical practice forward, the education, closing that education gap.

making physiotherapists of all ages, especially the ones that are now going into the practice, making aware of the most important factors that they need to know, that you’ve got to look at the big picture, you need to develop your clinical reasoning skills, you need to be able to translate, you need to be able to have great conversations, important conversations with your patients to set the expectations.

and need to have a good balance between your subjective experience and reasoning and having the coach’s eye and on the other hand knowing when and how to leverage technology in the practice. So I think all those different puzzle pieces you put together so nicely and it’s been wonderful chatting to you about this and it’s been wonderful collaborating with you so keep doing what you’re doing.

Bart Dingenen (01:12:42.724)

Thank you so much Kurt.

Kurt (01:12:44.378)

Yeah, and yeah, thanks for the time sharing your insights. I’m sure lots of physiotherapists are going to pick up some really good tips and tricks and at least think about what they need to do in terms of challenging their critical thinking and not just from bringing technology into the practice, but also looking at it in big picture and yeah.

Bart Dingenen (01:13:09.932)

Yeah, thank you. Thank you so much. hope listeners can enjoy it. anyway, if there are questions, they can keep in contact.

Kurt (01:13:19.001)

Yeah, we can listeners reach out to you, Bart. We’re with the BSB.

Bart Dingenen (01:13:23.235)

Well, my social media channels are open, like Instagram, for example, or I have my own website also, where the teachings are also visualized or listed. So my website is very simple www.bartdingenen.com. So it’s just my name and you will find it. And yeah, that’s a little bit…

how you can reach me, think. I’m not too difficult in that. yeah, that’s, hopefully we can get in contact for those who have questions. again, Kurt, thank you for the invitation today and for the collaboration. Thank you.

Kurt (01:13:54.075)

Yeah.

Kurt (01:14:08.175)

Great to have you on the pod. Thanks, bud. Cheers.