E9: Understanding the psychology of runners

with Tom Goom

In this episode of the Physio Insights Podcast, we’re joined by Tom Goom a.k.a. The Running Physio to dive deep into the world of running injuries. From uncovering the hidden causes and psychological hurdles athletes face, to tackling the crucial roles of energy availability, nutrition, and sleep, Tom shares his holistic approach to keeping runners healthy and strong. We explore how strength and conditioning, smart rehab strategies, and seamless collaboration with other health pros can help runners return to the track with confidence.

Key Notes

- Beyond “training error.” Load spikes matter, but the drivers all-out mindsets, go-hard groups, undervalued recovery set runners up to fail.

- Identity cuts both ways. Strong “I’m a runner” identity + obsessive passion → rigid persistence through pain; coach flexible persistence instead.

- Screen LEA early. Use PEAQ in session one. Inadvertent low energy is common in marathon/ultra blocks; loop in sports MD + nutrition when flagged.

- Carbs are not the enemy. It’s not just calories, low carbohydrate availability worsens bone risk and performance; refer for sport-specific fueling.

- Sleep is load management. Training up, sleep down = injury risk up. Protect sleep as the first recovery lever.

- Capacity pillars. Test the big four: calf, quads, glute med, hamstrings. Pick repeatable measures (HHD/10RM/calf raises).

- Impact ladder. Jog-in-place → jump squats → bounds → single-leg hops. Progress when symptoms allow; hopping often predicts run tolerance.

- Words change load. Reassuring, reversible-change explanations reduce pain during loading ditch degeneration narratives.

- Gait edits, not flaws. Lead with positives, then nudge: curb overstride, tame “medial collapse,” reduce excess bounce; small step-rate bumps go far.

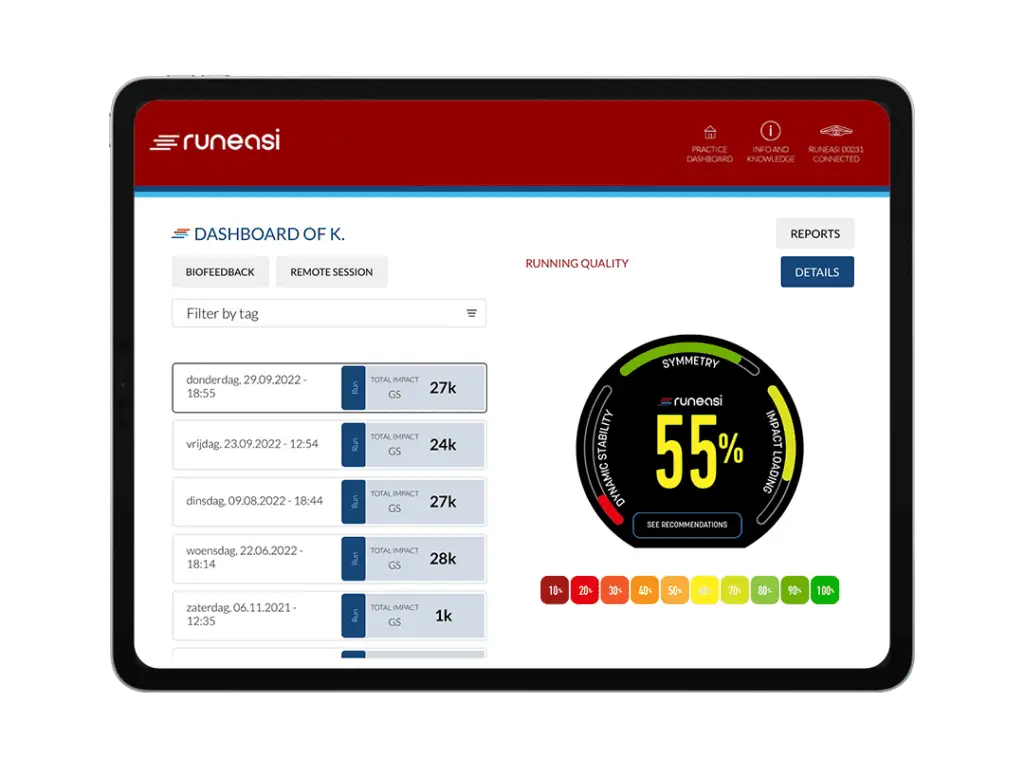

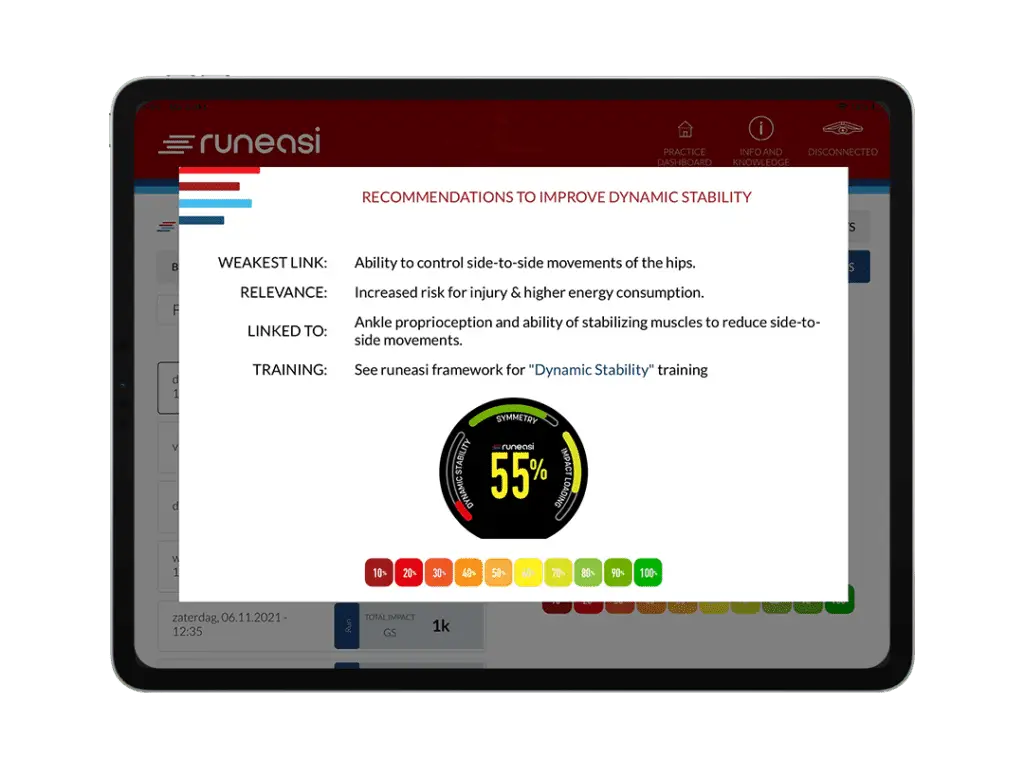

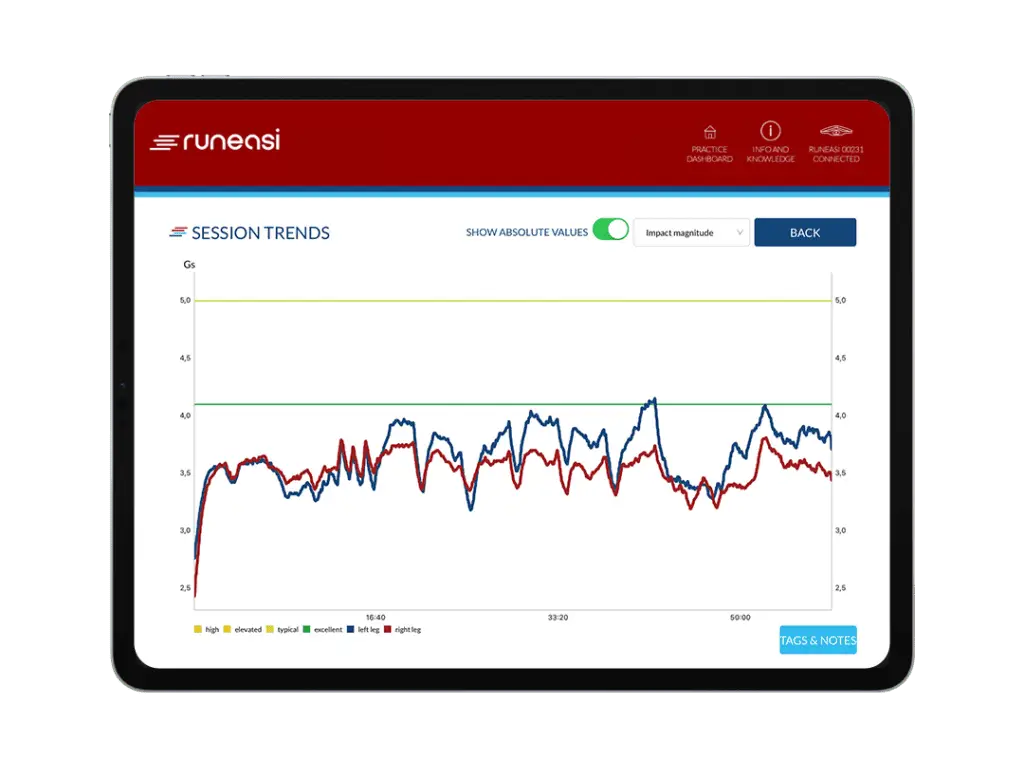

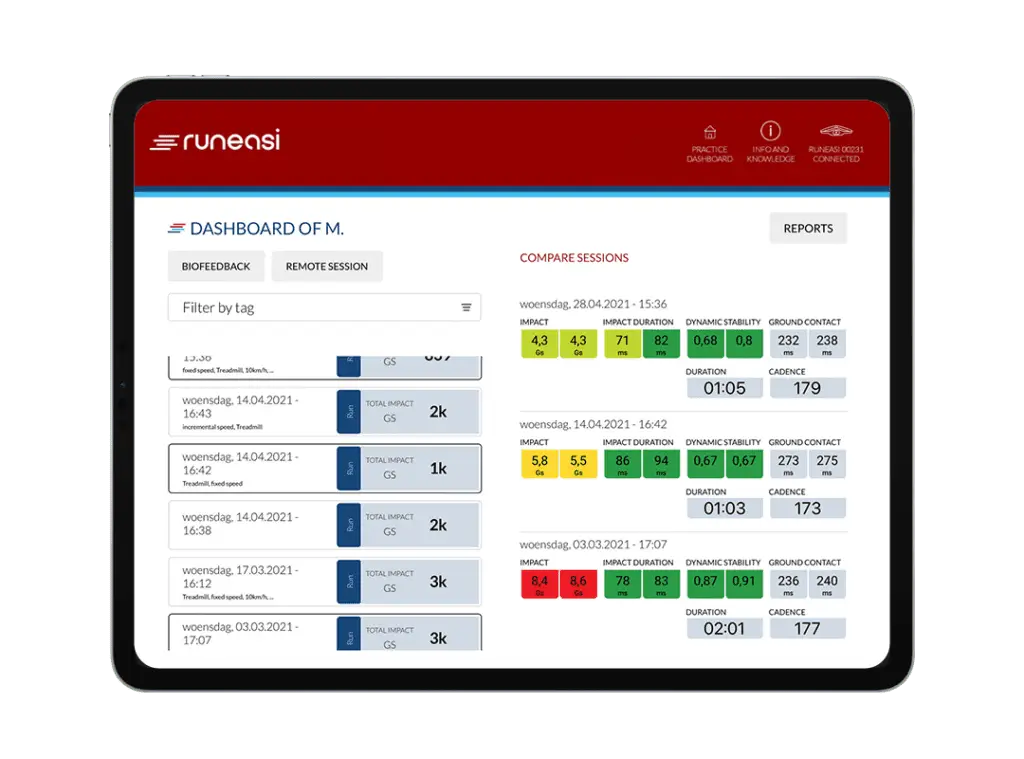

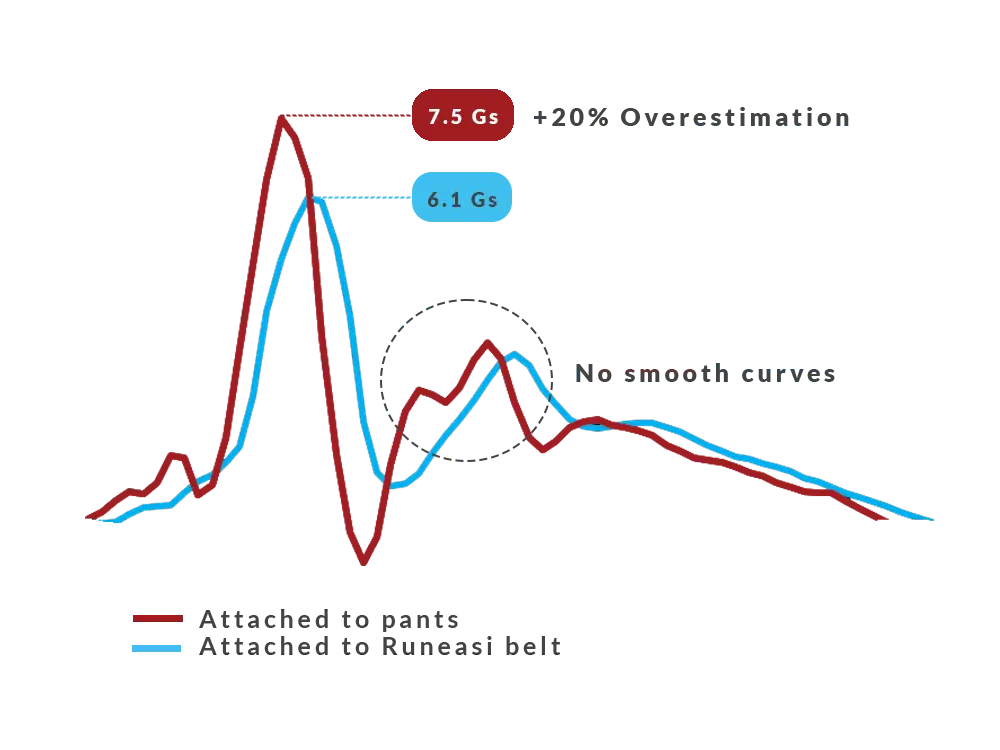

- Tech with purpose. Pair slow-mo video with field data. Runeasi quantifies impact/landing and symmetry for “in the wild” validation.

- Rehab = S&C, pain-aware. Decide: settle irritability or load for strength. Start where tolerated; progress via educated trial-and-error.

- Dose running responsibly. Walk-run and micro-progressions beat yo-yo flare cycles; “plateau, build capacity, then nudge” > constant resets.

- Normalize plateaus. Hold a tolerable 5K for weeks if needed; add strength, then extend consistency beats haste.

- Build your bench. Sports psych, nutrition, and coaching aren’t “outsourcing” they’re how persistent cases actually get better.

Full Audio Transcript

Jimmy (00:01.337)

Good morning, Tom. Welcome to the Physio Insights Podcast.

Tom Goom (00:05.986)

Hi Jimmy, thank you very much for inviting me on, I’ve been looking forward to it.

Jimmy (00:09.987)

Yes, as have I. I’ve been following your work for a long time. was fortunate enough to meet you almost a year ago at Park City’s running conference. But for those listeners that don’t know you, aren’t aware of you, could you introduce yourself?

Tom Goom (00:26.242)

Yeah, of course. So I’m Tom Goom. I specialize in running injury and that’s largely because of my passion for running and my love for physio. So I’ve combined the two together and have become known as the running physio as a result. So I have my website runningphysio.com. But I think those two things gel well together because I can see things from the runner’s point of view and then recognize why running is so important to them.

but also try and see it from the therapist’s point of view as well in terms of how do we get them back to that sport that they love and hopefully keep them back doing what they’re doing. So, it’s something I’m very passionate about. I do a lot of presentations and international speaking and lecturing and things on it and obviously write a lot about it on my website and social media and stuff too.

Jimmy (01:13.293)

Yeah, and how long have you been a runner?

Tom Goom (01:16.366)

Well, I would say I’ve probably been a runner about 30 years now. So I ran competitively as part of my school team, even as a teenager. Even before that, I was doing cross countries and stuff, even in primary school. So I’ve been involved in running most of my life and not so much competitive running recently once we had family, but I still love running. I still like getting out there and hitting the streets.

Jimmy (01:43.343)

Yes, I can relate to that having three kids now. All of a sudden, it’s quite the challenge to get out for even like 30 minutes, but still doing it. So then, yeah, the Running Physio, your Instagram and website, you offer a ton of content on there. And as I was digging into your work more, sounds like you started with, or tell me how that got started.

Tom Goom (02:10.67)

Well, I actually was mainly based in persistent pain before I specialized in running injury. And I worked with a really nice team in Brighton in the UK and they used to help run a functional restoration program. So it’s mainly based on people with persistent back pain, persistent neck pain, those types of things. So it’s very much based around education and encouraging people to get back to the activities they valued, improving their quality of life. And I liked that.

But the more I got into running and the more I treated runners, the more I actually realized a lot of these things actually are quite applicable in runners as well. But also I found that the other things I really enjoy like strength and conditioning and exercise prescription, like movement analysis, like planning the exercise and training programs are also part of it as well.

I think the more I learned about working with runners, the more I enjoyed it. And then that really took over as my main passion and main specialty. But think that interest in sort of persistent pain is still there because actually a lot of people I see who are runners are those more complex cases who’ve had more complex, persistent conditions. I really enjoy working with those people.

Jimmy (03:24.013)

Yeah, it’s funny. My career started similarly where I really enjoyed treating chronic pain and getting into that world. And I do think the carryover of kind of some of the topics we’ll probably go into shortly, but educating, empowering the patient, were all like things or skills that you and I probably honed back then treating those patients. And now we see the carryover with the running population.

But yeah, your Instagram and with the website, you’re teaching PTs. You’re trying to educate PTs and runners, or what’s your goal with it?

Tom Goom (04:05.996)

Yeah, so I would say most of it is aimed at people who treat runners. So most of it is aimed at health professionals like, as you say, physical therapists, physiotherapists, sports therapists, et cetera, podiatrists, people that actually treat runners. That’s probably where most of it’s focused now. But when I first started out, most of the content was aimed at runners who were looking to manage their injuries. And I think what I realized is that actually it’s quite difficult to do that because you can only ever provide generic advice online.

So it’s actually quite difficult to provide something that helps each individual. And of course you’ve got to be careful with anything you put online that people don’t interpret it as medical advice because you’ve never seen them, you never treated them. So what I realized over the years actually is if I made the content for the people that actually treat runners, that was a better way of helping runners, if you see what I mean. So that the therapists that are passionate about treating runners are able to have good information at their fingertips.

Jimmy (04:59.054)

I do.

Tom Goom (05:04.62)

and they could address their individual needs. And then people wouldn’t feel the need to go so much online where, as I said, actually it’s a bit hit and miss. That advice isn’t aimed at them, if you see what I mean.

Jimmy (05:15.587)

Yeah. So you’re, and you do a really good job kind of distilling the evidence, making it digestible for the clinicians so that, yeah, we don’t have to dig through all the research papers unless we want to, we can kind of do that. But yeah, I love your Instagram. It’s been super helpful for me, your blog as well. Yeah. So I kind of take in the next step. And as you have started the journey of working with runners, focusing on treating runners,

Off air, we briefly talked about this, where, I guess, yeah, what do you feel like sets the runner up for the path of injury? Where do you feel like the problems kind of start for most of these runners?

Tom Goom (05:58.424)

Yeah, it’s a great question. Thank you for your comments on the Instagram and stuff. That’s kind of you. I’m glad it’s helpful because that’s really my goal of wanting to help clinicians and be accessible. Yes, so coming back to that question, what sets people on the path to injury? I think we really want to try as much as we can to sort of understand the person with this. And I know sometimes that’s a bit of a buzz term, but…

By that, it’s trying to have a look at how things interlink together. So classically, we might think that 60 to 70 % of running injuries are due to training error. So the simple explanation would be your training’s changed too quickly, therefore something’s overworked and it hurts. And that’s okay as a superficial description, but I think if we’re understanding the person, we can go a little bit deeper and say, well, why did you end up with that training error? What has led to that training behavior?

And are we able to identify those drivers and help you change them? Because if we’re not, is there a chance that once your symptoms feel better, you’re actually going to go back into those same training behaviors again and get the same training errors and you’ll be coming back to us with something new. So I try and think a bit more broadly behind it. Yes, it might be training error, but what are the beliefs behind the training?

So does the person, example, feel they’ve got to go 100 % in every session? I’m sure Jimmy, you will have worked with people like that. They don’t think they’re training unless it’s 10 out of 10 effort. Do they really undervalue rest and recovery? They see it as weakness, so they avoid it. What’s the training group there with? Are the training group people that are pushing themselves all the time, that kind of go hard or go home attitude? And if we give them the green light to go back into running and they go back into that group.

are they going to be set up for the same problem again? So you think it’s that process of getting to know those pieces of the puzzle for the individual so that we can help them best, I think.

Jimmy (08:00.205)

Yeah. So when, when an injured runner presents to you, this is where you’re going to start is looking at kind of hearing their story and trying to unpack the behaviors behind why they’re training or acting the way that they are. And you had a, you had a really nice post about this where, it was the, athletic identity post. Can you speak about that? It’s either you you’ve been kind of talking about it, but could you be more explicit about it?

Tom Goom (08:26.326)

Yeah. So there’s lots of different areas that have been looked at within, within psychology and its link to injury. And they tend to overlap quite a bit. so the post you’re referring to, we were talking about some of those factors that might lead people on the path to injury. So one is one factor is athletic identity. And by that, we tend to refer to someone who sees themselves as a runner or as an athlete. I am an athlete. That’s who I am.

It’s a huge part of their life and their identity. So when they’re injured, they really struggle with that. And it’s quite common for that to go in hand in hand with other things like what we call obsessive passion. And that’s tending to feel that you really must train. You’re really so focused on that training that the training essentially takes over. And that can lead to what we call rigid persistence.

this need to keep going, keep going, keep going, despite the negative impacts that running and training might be having. Despite the fact you might be fatigued, you might be injured, it might be having an impact on your work life, your family life. You feel you just have to keep pushing and keep going. Now that often will be linked with beliefs. So that person may believe, like we talked about, they have to push hard in every, every session and that continuing through pain means they’re strong and resilient. But

On the flip side, stopping resting, taking care of themselves, recovering is weakness. So it can be quite a complicated combination of different factors that set someone up for a training plan that they just can’t cope with long-term and that leads to injury.

Jimmy (09:57.039)

Hmm.

Jimmy (10:10.883)

funny, Tom, you’re I feel like you just described me. So I’ve been kind of wrapped up in that for a long time. I do think as I’ve gotten older, it’s been easier to kind of step away from that identity. I do think it was quite hard. And yeah, you it speaking from experience, it’d be you live in this very rigid world where it’s you have to do this. There’s no other option. It’s like

that you rationalize everything, a little niggle that is more than a little niggle, you’re telling yourself it will just work itself out. And then also, like a lot of patients I see have that same belief pattern. So when you do uncover it in the clinic, like what’s the next step?

Tom Goom (10:55.694)

Mm.

Tom Goom (11:01.912)

Yeah, good question. I mean, you used a good phrase a moment ago, which is, you you start by hearing the patient’s story. And that’s very much what I try and do. I like to ask people, you know, how did your injury begin? Can you tell me a little bit about the injury and how it’s progressed for you? And then I try and be quiet for as long as it’s necessary to give them the opportunity to offload the important, the key stuff. And it’s once you’ve

Once you’ve got that key stuff and you’ve heard their story and you’ve reflected it back to them a bit, so they know you’ve heard them, because I think that’s important, then we might start to sort of pick away a little bit into questions behind it. So perhaps they’ve told you, I’m training really hard for this event, and then you dive into the training and you see, yeah, you’re doing like 10 sessions a week, there’s no recovery days, lots of it’s high intensity. We might then ask the question of like, why have you chosen to train in that way?

And again, trying to be quiet and let them share with you, well, I feel like I need to do that much volume because that’s how I’m going to improve my performance. I’ve read, I need to do this much intensity. So, you know, I just don’t feel very comfortable taking rest and recovery. That then allows you to explore those things a little bit so that you might be able to soften that stance or look for flexibility. it’s flexible persistence instead of rigid persistence. And often the

If someone’s injured or has a fixed mindset, they won’t see the flexibility that is within that week, that structure that you can change. So that flexibility might look like replacing sun running with cross training. It might look like keeping the distance the same, but dialing the intensity back. It might look like taking hills out and replacing it with something else that’s less provocative. It might look like planning the structure so that you don’t have a big block of high intensity in one lump.

Jimmy (12:44.397)

Yeah.

Tom Goom (12:58.872)

So there’s often lots of flexibility there if you can help the person see it.

Jimmy (13:04.557)

Yeah, you’re making me think of a patient I worked with who was very high level ultra runner. She was sponsored by a shoe company and I was seeing her for stress fracture. She was recovering from a stress fracture and we had talks about her training habits and style like this, like what we’re describing. we took, like I heard her out. She came to this conclusion that

When she gets back to training, her volume will be limited to X amount and she’s going to cross train two times a week instead. As soon as she got healthy, guess what she was doing right back to the old behaviors. like somebody like that makes me think like, all right, this is maybe out of our wheelhouse as a therapist, as a physical therapist or a physio. And so, are you often like referring out in cases like that? Or is that, what do you do in that scenario?

Tom Goom (14:00.834)

Yes, I’m a big fan of working with other health professionals. I think you’re right. you don’t feel able to meet the patient’s needs for whatever reason, maybe it’s not in your scope or you just don’t feel you’ve got the confidence and competence to do it, I definitely would refer out. So I do that with training plans too. If I don’t feel I’m able to meet someone’s needs for their performance, perhaps, if there’s a more performance-focused plan, we’ll team up with a running coach.

And if there’s concerns around mental health and beliefs and things, yes, we might team up with their counselor. The post you’re talking about we did recently was with the injury psychologist, Carl Biscovi, who’s brilliant. So we might refer to Carl and say, perhaps this would be an option. Obviously discuss it with the patient first. But yeah, it’s part of what I would consider psychological readiness to return to sport.

Because we think about physical readiness, don’t we? And I think most of us would test that. We would look, you know, do they seem physically ready? Can they tolerate impact in running? Have they got enough range, enough strength, enough control? Are their symptoms going to tolerate that? Are they at the right stage of the healing? And we would make sure they’re physically ready. But in patients who’ve had a history of very high training volumes and particularly multiple injuries, I would also be quite careful to say, well, are they psychologically ready?

Do they have a relationship with their sport that’s driven by obsessive passion and rigid flexibility, rigid persistence, keeping going, keeping going? If so, are they psychologically ready to return to their sport? Are they going to go back into the pattern that those problems have actually driven in the past? If you see what I mean.

Jimmy (15:45.487)

I do. I, cause I know like I’ve tried a lot of this my own, on my own, and a lot of times feeling like it just, it flops or it doesn’t really land with the patient. And it sounds like you’ve done a good job. Yeah. Cultivating a team around you so that when that ha or if that happens, you’re ready to just say, why don’t you talk to my colleague over here? Was that, was that intentional on your like?

Tom Goom (16:11.395)

Mm.

Jimmy (16:14.967)

with your clinic, like you have maybe a dietician, you have a sports psychologist that you’ve networked with.

Tom Goom (16:22.146)

Yeah, I would say it’s something I’ve been working at getting better about over the years because we all reflect on our practice. And one of the things I’ve reflected through the years is to try and be better at actually working with other health professionals to get the right support for the patient. Because I think sometimes we feel we’ve got to do it all. And we’re trying to do a bit of psychology, a bit of nutrition, a bit of training planning, a bit of strength and conditioning. And actually that might not be the best solution for the patient.

Jimmy (16:40.845)

Yeah, I think.

Tom Goom (16:50.296)

So I’m trying to be a bit better at saying, okay, you know, how would you feel about perhaps speaking to my colleague, Carl, about this to help explore some of those training drivers? Would you be interested in chatting to him and seeing if that’s something that might be helpful for you? you know, trying to normalize that process as much as possible. So he might come in first by saying, actually, you know, a lot of runners find it quite hard, the mental aspect of injury.

because they’re missing a sport that they love. It’s a big part of their life and their social life. A lot of runners tell me that’s difficult. How have you found it? So it normalizes it to open up the conversation. And then when they say, you know, I’ve really struggled with that, actually, the mental side’s been as hard as the physical side. Okay. Would you think you might benefit from some extra support there? And that might then be the way that you come into those conversations and, you know, encourage them to get the support.

elsewhere. And of course, there’s a lot of overlap between these different areas. So another area overlaps with a lot is energy availability.

Jimmy (17:54.851)

Yep. Yeah, go ahead. Speak on that.

Tom Goom (17:58.222)

Well, know, you know, a listener is not familiar with the term, so energy availability is really important for everyone really, but particularly with athletes and those doing high volumes of training. So what this essentially is, is we’re looking at how much energy they’re expending. So that’s with their sport, but also day-to-day life as well, versus…

how much energy they’re actually taking in through their nutrition, their diet, their fueling, et cetera. And unfortunately, some people, if they have a high energy expenditure, they’re burning a lot of fuel with day-to-day life and sport, and they’re not taking on much energy through their diet and nutrition, they end up energy deficient. And that we know is a potentially big factor for multiple injuries and impairs performance, increases the risk of race day complications, all sorts of things that link to that.

Now there is an overlap you’ll see from some of the studies between things like exercise addiction and eating disorder. They do quite commonly coexist. So you might have someone in that situation who’s no longer in control of their sport, the sport’s driving them. So they have very high training demands and they are restricting their calorie intake because of their eating disorder.

And that then is going to be a big factor leading into energy deficiency and injury. So I think just a little action point for people, there’s a really fantastic screening tool you can use for energy availability called PEAQ. Perhaps we can put the link in the resources afterwards. Totally free. It’s produced by Dr. Nicky Keyes, he’s lots of research in this area. And the patient fills it out anonymously online and it produces a report for them.

so that you can have a look at what their energy availability is. And because there’s such an overlap between this eating and training, I think it’s a really useful piece of the puzzle in this process. So this is something I’m doing session one with my patients now. I explain it and I say, between now and the next session, would you be open to filling out this questionnaire? And nearly everyone says, yep, no problem. We explain why. Once you’ve done it, if you can just send me the report, I’ll have a look on it. We can discuss the findings next time.

Jimmy (20:11.727)

Yeah.

Jimmy (20:21.879)

And is that with every patient or just one?

Tom Goom (20:24.01)

Every patient that I see that is involved in sport, majority of patients I see are runners, but I also see a lot of people with persistent tendon pain who may be inactive. So it’s probably less of a priority for those. But I think it’s routinely with runners, it’s such a quick, easy thing for them to do. And I don’t really think there’s a downside. So I think as part of our screening, it’s useful to do.

Jimmy (20:49.881)

Yeah, that sounds great. Yeah, we’ll definitely link it in the show notes here. And yeah, so it also makes me think about, I work with a lot of ultra runners and I tend to see a lot of inadvertent low energy availability. It’s unintentional. They think they’re eating a ton, but they’re exercising so much that they can’t keep up with the intake.

Tom Goom (21:17.762)

Mmm.

Jimmy (21:19.008)

Have you seen that as well?

Tom Goom (21:20.846)

Absolutely. I think there’s many cases where yes, it’s exactly that. It’s not a deliberate choice. It’s perhaps people not realizing, particularly with ultra events or training for marathons, just how much they’re burning in terms of calories. So there was a study recently from Kristin Whitney at all, which found, I think it was over 40 % of women training for the Boston Marathon who they were surveying had low energy availability.

Jimmy (21:36.302)

Yeah.

Tom Goom (21:48.942)

was a bit less in men. It could be somewhere around 40 % of women in some populations. It probably is quite a lot more common than we think, hence why it is worth doing that screening.

Jimmy (22:03.043)

Yeah. think it’s, vote like historically for me personally, like I’ve, I look at when I’m training high, anytime I started to feel crummy, anytime something’s going wrong, my first solution is just eat more. And I feel like it’s worked for me very well. my, one of my first major injuries as a runner was my freshman year in college. I had a sacral stress fracture because I, I was

Tom Goom (22:18.125)

Yeah.

Jimmy (22:29.739)

I had a lot of GI issues and was under eating because I was scared to eat before I ran and led to this sacral stress fracture, which was not fun and took me out for quite a while. And so I think since then, I’ve just like food has become for me the answer most of the time. But a lot of times, yeah, you see folks who it’s, they’re just not aware of how much you actually need to eat. Also.

Tom Goom (22:42.702)

Mmm.

Tom Goom (22:56.014)

Absolutely. mean, that that what you’ve described there, that story is really good example of like, like that’s the person like that. It’s not just looking at right, you’ve got a sacred, you know, stress fracture, we do this, it’s like, okay, well, what’s led to that? What’s, you know, what’s led to that situation? And interestingly enough, one of the signs of low energy availability is gastrointestinal issues. So that that sometimes can be a symptom of it.

Jimmy (23:21.059)

Yeah.

Tom Goom (23:24.846)

So these are other things that if we’re picking them up in our subject to exam might make us think, hang on a little bit, like maybe there’s something bigger going on. And just to try and give people a little bit of an example of like how might these kind of care pathways work in real life. So was working with a runner recently who was describing what I felt sounded like a high risk stress fracture.

And we know, of course, energy availability is really important for that. So we asked her to do her peak, her energy availability questionnaire, which showed up that yes, she did have signs of low energy availability. And we recommended a nutritionist that we work with to consult on that. Because it was a high risk stress fracture, we referred to a sports physician because we felt we needed urgent imaging and their input on it.

but also because sports physicians are often those professionals that might lead the team for a more in-depth assessment of energy deficiency. So I’m not going to carry all that on my shoulders. I’m going to be the sports physician, I’m nutritionist and physio. It’s like, okay, now we’ve got a team in place and then we try and make sure that team communicates. So with each other and with the patient so that they’re getting the best care.

Jimmy (24:25.391)

Mm-hmm.

Tom Goom (24:49.102)

out of that.

Jimmy (24:50.531)

Yeah, that’s awesome. Because I do think it’s like, see personally, I feel this pressure. You described the pressure maybe earlier in your career of, yeah, trying to be everything, trying to be the nutritionist, trying to give the coaching advice, trying to do the strength training. And I do feel like.

it’s hard to let that go and to refer somebody out. at times I often feel, as a clinician will feel somewhat guilty that I’m asking this person to now go spend more money somewhere else on another thing. But it sounds like it’s just, we have to look at it as this is what’s best for the patient.

Tom Goom (25:29.026)

Yes, and it’s just recognizing where your skills and expertise kind of end, really, and, you know, and is it in the best interest for the patient to see someone more specialized and sometimes it isn’t. But it’s also sometimes reflecting on us, like, we come into these professions because we want to help people. And so naturally, it’s one to help, we want to help people in all the ways we can look, there’s like 10 things I can do to help, which is really good. But it’s just looking at

like when might there be a need for something else? And that’s why things like our screening tools like Peak, that helps us to see actually, you know what, we’ve got a clear need here for this to be looked at in more detail. The test is showing up. You’ve really got quite low energy availability. Let’s really get the right person involved versus this is coming back fine. There’s no issues there. We could have a little bit of a general chat about how you’re choosing to fuel and things, but we probably don’t need to refer on. Do you see what I mean?

Jimmy (26:23.671)

I do, yeah, I love it. One more thing while we’re on this topic. Can you talk about the role of low carbohydrate availability?

Tom Goom (26:35.438)

Now, I will be honest here and say I don’t understand and know a huge amount in this. The only thing I would say that I’ve picked up is as I understand it, it isn’t just important to take on energy. There does seem to be benefits specifically in including carbohydrates within that. as I’m not a nutritionist, so I can’t talk much more about it, but it does seem to be important to contain.

carbohydrates. And I know some people like the low carb diets. And this is another reason why I’d refer to nutritionists. Some people have restrictions in terms of what they can eat specific preferences. The nutritionists we work with are brilliant at then looking at that and saying, right, how do we make this work for you? They use all that knowledge and experience say, okay, you prefer this particular diet. Let’s find a way to make that work for you if you see what

Jimmy (27:27.307)

I do. guess reading through the IOC statement on reds that they put out maybe two years ago, 2024, I think. So a year ago. Yeah, they brought up just low carb availability, potentially being more harmful than low energy availability, having negative effect on both bone formation and bone resorption. But yeah, I’m also not an expert.

I gotta find somebody to help me understand this better. Because I do think like in the social media world and the influencer world, you see over the past five years or so, a big push for protein. And so I see, I’m getting a lot of patients that are coming to me and when I start digging into energy availability questions, they’re telling me things like they focus on protein first, they’re trying to hit a very high protein goal.

Tom Goom (28:08.206)

Mmm.

Jimmy (28:24.205)

And I’m suspecting a bone stress injury with this patient. And it’s just like, I feel like I am seeing that more.

Tom Goom (28:31.534)

Yes. think social media, because you don’t necessarily have to have any qualifications in the topic to talk about it. And because it polarizes views, I mean, it seems that the most polarized view, opinions get the most attention that we don’t necessarily get, I think, the best.

view. But I agree, what you were saying about carbs there mirrors what I found in one or two studies that I’ve read that there seems to be benefits specifically, not just of energy intake, but ensuring that comes from carbs. And the nutritionists we work with, they’re from the called the performance canteen. And one of their phrases is carbs are the energy, not the enemy. So they are trying to sort of move away from this idea that there’s a negative around carbs.

And actually one of the reasons I like working with them is they look at really accessible, simple food ideas. It’s not about some super food or some supplement you need to pay a fortune for. It’s what you have that actually you can use regularly that meets your nutritional needs. And I’m a fan of that really, because I think that’s more real world, more realistic.

Jimmy (29:41.871)

Yeah, 100%. All right, so so far we’ve talked, we’re starting on this journey of yeah, what leads a person down the path to injury? We’ve talked about training errors being something. We’ve talked about the athletic identity and kind of the psychosocial component of or compulsive behaviors, exercise addiction, and then now fueling. What else, is there anything else there before we kind of move on?

Tom Goom (30:08.492)

Yes, good point. So on top of that, think we could look at other aspects of recovery like sleep. I think that’s really quite important as well. There seems to be a growing body of evidence that lack of sleep can be a factor in the development of injury. We think it’s probably our best form of recovery. And that’s going to interact then with things like the energy availability and the training. If your training is building,

and you’re not increasing your sleep to compensate, then you’re not getting enough recovery potentially. In fact, most people when training increases a lot, sleep less because they’ll often need to fit the training in early in the morning or late at night. So they actively sacrifice the sleep in order to train more. So I think sleep’s another part of it potentially. And any sudden change really, so we talk about change in training obviously is part of that.

But it might be other things like change in footwear. So someone’s decided they’re going to try a very different shoe style. Maybe they’re going to move to a more barefoot style shoe that they’re not used to. Or there’s a change in their running gait. They’ve decided to try a forefoot strike when they’ve been a rear foot strike most of their life. The body doesn’t cope with very large changes to tissue load. So those can be a big part in it. And then we’ve got our physical capacity things. They do make a difference.

strength, muscle strength, movement control, flexibility, changes within the tissue sometimes. So I think there’s lots of those things that are going to interact to give us the whole picture, if you see what I mean.

Jimmy (31:46.029)

Yeah, are there any specific or key assessments for capacity that you’re using and that you think maybe PTs are missing or you want to make sure that we are all doing these certain tests?

Tom Goom (32:00.13)

Yes, I tend to try and test the four key muscle groups that carry very high peak globes. And I know of course, you and I have talked about this a bit before, but looking at things like the calf and the quads, the glutes, particularly glute med and the hamstrings, those are muscles that do carry high peak globes. Now there’s lots of different ways that you can test them. And I think it really will depend on the clinician and what they have access to in terms of how they do it.

One option is our reps to fatigue tests. So looking, for example, at how many calf raises can someone do on one leg before they reach fatigue to test the calf. Now these are useful because we don’t need much kit. But the downside is how you test it matters, but also it’s a combination of strength and endurance. And each of the tests we do, they have these kind of pros and cons. If someone’s got access to a little bit more equipment, we might use things like handheld dynamometer.

particularly useful for things like glute strength, hamstring strength, or load them up in the gym and be testing things like 10 repetition maximum or above, which is going to be a little bit closer to a truer strength test. So I think if people are trying as part of their assessment to look at those key muscles at some point, that is important. I would also include impact. One of the things that separates running from everyday life is the presence of impact.

So we need to see that people can tolerate that in terms of their symptoms when it’s the right stage of their recovery and they can perform that well. those are some of the things, and we have a whole course of stuff you could delve into, there’s loads more, but those are some of the things I would try and include.

Jimmy (33:45.103)

Could you elaborate on like one or two of the impact tests that you would do?

Tom Goom (33:50.946)

Yes. So with this, a quick, important point to say with this is we always need to assess when it’s going to be safe to do this. You know, if you’ve got someone walking in with very irritable symptoms, really all the signs and symptoms of a high risk bone stress injury, we’re not going to get them leaping about. know, so that is an important caveat here, but usually if we feel it’s safe to do it, I start with jogging on the spot for a minute. So we start with light impact and we’re looking to see, does this provoke any symptoms for them?

Because if they can’t jog on the spot for a minute without pain, it’s very difficult to tolerate much running. We can also look at how they’re doing it. Do they seem to be landing in a similar way on both sides? Does it feel similar to them? Or are they trying to avoid loading? Now, if that’s pain-free and manageable, we might say, OK, let’s test a bit more. Let’s go to jumping in place. So jump squats. And we tend to do 10 reps. Same idea. Is there any symptoms? How are you controlling and performing that test?

You might use something to test it more in detail, like a force plate, or there’s various apps out there that you can use to actually get more more data from that. That might then go on to the next test of things like bounding, and usually again, 10 bounds, so maybe five on each leg, and finally onto hopping, 10 hops on each leg. So we’re progressively making these tests more challenging, providing they’re symptom free and it’s safe to do so. If someone can hop repeatedly without any pain,

then usually they will tolerate some running. So that can be useful, but just thinking about when the right stage to test that is.

Jimmy (35:22.799)

And yeah, as you progress to the more advanced and unilateral hopping, you’re looking for, if you’re not collecting data, so RunEasy does offer like, you can do single leg hopping and does do symmetry. I don’t know if you’ve seen that. But if you’re not collecting data, are you just looking at like subjective feeling? Are you looking for quality of movement? What are you looking at?

Tom Goom (35:47.778)

A bit of both. first of all, if we’re trying to see is this person ready to do some running, we’re looking at symptoms. That’s probably the most important thing. you know, can they manage impact without bringing on their pain? Beyond that subjectively, yes. How does it feel? think, I think, you know, we really want to ask the patient, you know, that how does it feel? Does it feel any different left versus right? Because they’ll often say to you, yeah, I don’t think I’ve got quite the same spring on that sore side. I feel like it’s

It’s a little bit flat, it’s lacking a bit of power. And then we can have a look at how it looks. So we might take a video and look at it in slow motion to actually see what’s the movement pattern like. So let’s say, for example, you’ve got someone coming back post ACL reconstruction, and they’ve reached that point of recovery where you feel like it’s now an appropriate timeframe. They’ve hit the key strength markers and everything else got quite comfortable knee, and we want to look at them hopping.

So some of them, when they hop, will actually avoid going into deep knee flexion to offload the knee. So that might show up in your assessment. They’re actually not actually taking the knee into the kind of ranges they would typically do. So that might then allow you to say, okay, well, let’s have a look at restoring that a little bit more before we progress onto the next stage.

Jimmy (36:49.219)

Yeah.

Jimmy (36:57.454)

Yeah.

Jimmy (37:05.141)

Awesome. that’s where, like, with run easy’s jumping assessment, you can quantify that. And it’s pretty neat to see left versus right. Cause I had a similar case that I’ve talked about before on the podcast of a post-op ACL where we were basically exactly what you described. And I was able to, we can visually see it, but then we could quantify it with a landing score and metrics, which was pretty awesome to see. because she was at a stage where the.

symptom wise, that wasn’t what was driving it. It was the performance that she wasn’t able to return to sport. yeah, so the next step then, where does something like a gait assessment or gait retrain, or yeah, gait assessment fall into the equation?

Tom Goom (37:52.374)

Yes, good question. If I can just come back to the hopping for a moment, just for a moment, because there’s a really interesting study that’s just been published from Travis et al. And that actually looked at how we as health professionals describe injury to a patient and the symptoms they then get during a hopping test. So I thought I’d kind of sandwich this in because it’s quite relevant to the hopping we’ve just done.

Jimmy (38:16.751)

Please. Yeah.

Tom Goom (38:19.308)

So very, very brief overview. They did a study of 50 runners with Achilles tendonopathy. And they actually had a very clever study. So they told the runners, we’re actually just looking at like stiffness during hopping. They didn’t actually say, our main aim is to look at whether we can change your pain. So what they did is you’ve got these runners and they did baseline tests. They got them all to hop. I think it was 10 hops on the affected leg. And they got them to score their pain, like on a VAS scale out of 100.

and they looked at stiffness, leg stiffness, similar to what you’re talking about using the run easy stuff. So those are the baseline tests. Then they described the Achilles tendonopathy to them. And one group were the control group and they got your kind of traditional explanation that your pain is down to changes within the tendon. They’re not likely to be reversible. There may be a degenerative component to this.

The other group got an explanation that was much more focused on reversible changes, much more positive. So something along the lines of your tendons in really good shape, it’s doing fine. It’s a bit sensitive at the moment. And we think that’s because the muscle needs to be a bit stronger to help the tendon. And what they found then is when they repeated the hop tests, those with the more positive explanation of pain scored less in terms of pain.

than those who’ve had a more negative perception of pain. So this is what we’re talking about with things interlinking. It might actually be that our words that we choose, our explanation, our education can actually influence pain during loading, which is again why I think it’s so important to try and see that kind of whole picture and how it comes together.

Jimmy (40:05.763)

Yeah, and that’s awesome because that I feel like maybe 10 years ago, 15, when I was first graduating from PT school, so let’s say like 2010, 20, in that timeframe, this kind of research was coming out for low back pain. And now we’re seeing it kind of trickle out into the sports world. Did you see that back in your early career when you were focusing on persistent pain?

Tom Goom (40:32.494)

Absolutely. And that was a big part of what we were trying to do in this functional restoration program was trying to reframe pain and actually sometimes trying to undo a little bit some of the messages people had received from previous health professionals. So because best will in the world, we’re trying to explain something that’s complicated and it’s a natural thing to sort of say, okay, there’s this thing wrong in the tissues and that’s why it hurts.

And actually, it may be that there are other ways we can describe it that are a little bit better, you know, for the for the patient. You know, you think about with back pain, we had all that stuff of people being told that their disc was like a donut jam squirting out, you know, those types of things. No, not so much. I think there are better ways.

Jimmy (41:20.207)

Yeah.

Yeah, I think it, remember probably first five years of my career, I really struggled because I was, I gravitated more towards this optimistic approach. But as a clinician, I felt like I was perceived by the patient as being less educated. I didn’t understand as much because I wasn’t using all the fancy words saying your SI joint, this F.

all the things weren’t in place and saying all that, I was giving a more simplified explanation saying your back is sensitive, irritable, not tolerating load very well. But it’s now, yeah, now I feel like the profession seems to be evolving. We’re talking more like this.

Tom Goom (42:05.422)

It does. But I actually had a similar experience, Jimmy. And I think what I reflected on it was I felt that reassuring people in that way was going to be helpful. But what I learned about how I was doing it was I think it may have come across as a bit dismissive, that they were coming to me with pain that was really affecting their quality of life, they were really struggling to cope.

and they maybe felt my answer was a bit dismissive. it’s just a bit sensitive, there’s no real damage and that doesn’t really validate their experience. So I think that’s one thing I took from it and that is hard, that is a hard side of it and it’s then trying to perhaps broaden that explanation a little bit more for those patients and trying to find a way of saying, yeah, I can see this is really affecting you, you’ve had a tough time with this.

A lot of people have a really challenging time with this type of condition. A lot of people find it affects them like it’s affecting you. So we really make sure that they feel heard. And then maybe we go onto a little bit more of a detailed explanation that ends up in that same place of your back is healthy. But sometimes takes a bit longer to get there. You see what I mean?

Jimmy (43:23.169)

I do a hundred percent. So when we move on to the, do in a gate, a gate assessment or looking at a runner’s gate, think the same, can keep that same idea going with how we talk to the runner about their gate. I feel, when I first started practicing, I was trained to, yeah, point out all the flaws, all the bad things that I see. And then.

over time realizing that the patient’s leaving with just like a laundry list of all the things they do really bad. Is there a better way? What do you? Yeah.

Tom Goom (43:57.324)

Yes, that’s such a good point, isn’t it? And I agree. think, especially when you look at the overall assessment we’re doing, they might be going away thinking, okay, I don’t run very well. I’m weak. I’m stiff. I’m tight. You know, the whole list, not just the running game, a whole list of things. And that can be quite overwhelming. I try, it’s another thing I’ve reflected on. And I try to deliberately point out positives in people’s assessment.

And I try to reframe what might’ve been seen as a negative as a solution if we can. So one of the things I try and get people to do on the running repairs courses is actually stop and say, what positives would you be able to pick out from this person’s assessment if you’re looking at their muscle bulk or alignment? What would be the good things? Because there’s no reason why we can’t say to someone, do you know what? You’ve got really good muscle definition in your legs and actually your alignment’s really good. There’s no reason why we can’t point those things out.

Jimmy (44:51.439)

Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Tom Goom (44:53.71)

And if there is something we might want to help them with, instead of saying, yeah, but your calf is really weak. We could say you’ve got really good alignment, your muscle bulk is good. If we can get that calf a bit stronger, I’m sure your Achilles will feel a lot better. So it’s a solution and it would be similar with the running gait. you’ve got a really nice upright running style. I think how you propel is really effective actually. You can see that that’s part of reason why you’re fast as a runner.

Jimmy (45:08.302)

Yeah.

Tom Goom (45:22.09)

think if we up your step rate a little bit, I think that will reduce the stress on the knee and I think that’ll make you quite a lot more comfortable. Instead of my least favorite thing in the world, I hate it, is you’re not built for running. We should never be telling someone who is a runner that that’s completely no, you know, there’s no good things that come from telling someone that.

Jimmy (45:29.667)

Yeah.

Jimmy (45:40.878)

Yeah.

Jimmy (45:44.791)

Yeah, we can tie it back to that, study you mentioned with, yeah, words matter. So when you’re doing your Gaten assessment, choosing your words wisely, pointing out positives when you can, probably leading with that, and then addressing things that potentially we need to work on. And when it comes to running mechanics specifically, are there certain things that you’re looking for that you do typically try to change?

Tom Goom (46:05.58)

Yeah, absolutely.

Tom Goom (46:14.69)

Yeah, so there’s probably three main areas. And this is something that I know we spoke about before the podcast. We met up in Utah. It’s something that was presented at Utah. Brian Hidershite, Rich Willie and others talked about this. And so I’ve got a similar approach to them. I think probably the main three things I would look to potentially address would be overstriding, what we call medial collapse, not a very nice term, but where we’re getting a lot of pelvic drop and hip adduction.

or high levels of vertical oscillation, so very bouncy running style. And the reason why I’m particularly interested in those three things is because we have research linking those two increasing load on various tissues. So for example, if you’re over striding, we think that’s like to increase the load on the knee. So it comes back to that idea of, are they moving in a way that’s putting more stress on the sensitive area? And if so, can we then change that?

Jimmy (47:11.363)

Got it. And then does tech play a role here?

Tom Goom (47:16.31)

It definitely can. It definitely can. think with our assessment, what I tend to use is obviously we want some video. So I tend to use slow motion video capture in order to be able to look at things frame by frame. So that definitely plays a part. As you know, I do tend to use run easy. And I think that can be really useful to give you additional data alongside what you’re able to actually physically see.

The other thing I really like using that for is we can get people to go out and run in the wild with the RunEasy and collect data from that. And I think that’s really valuable. So it’s not just how do you look when you’re on a treadmill in this very controlled condition, but how are you actually running and moving when you’re out there on the run? So yes, I tend to use things like RunEasy in there as well.

and I’ll often combine it with the data we’re getting from the patient’s own devices. So if they’ve got a GPS watch, which has things like training data and extra information, that can also be quite useful to add to what you’re physically seeing with your video analysis.

Jimmy (48:24.495)

Awesome. Yeah, I agree with that. think for me, clinically, like I need my 2D slow motion analysis. I want to see that 100%. I like collecting the data from RunEasy. It’s objective. I can show it to the patient, easy to understand. And then I always get, I don’t know if this resonates with you, but lots of pushback on the treadmill where the patient says things like, I never run on a treadmill.

I don’t run normal on a treadmill, so they always want to go outside. And the ability to like, put the belt, run easy belt on and just go outside, maybe just like eases their mind a little bit more that you’re actually seeing how they are, like you said, in the wild.

Tom Goom (49:06.272)

Yes. Because the other thing is when we’re talking about running gate analysis, we have our generally the two main ways we do it. So it would be on the treadmill and overground. So treadmill has its benefits because you can get that high quality footage and you can calculate things like step rate and you know the speed it’ll say it there on the treadmill. You can get multiple views. But one of the downsides of overground is you don’t know speed.

You don’t know step rate. You may be able to get some data from their GPS watch, but it’s not very easy to do that if they’re doing a very short run with you, perhaps up and down a short runway in clinic. So that’s where having some extra tech and combining that with what you’re measuring and testing in clinic, I think probably gives you the best of both worlds really.

Jimmy (49:34.116)

Yeah.

Jimmy (49:55.853)

Yeah. so the, guess, moving forward through the journey of the injured athlete, as you, I guess, where does strength and conditioning fit in with home exercise rehab, or do you kind of see that all as the same?

Tom Goom (50:12.046)

Yeah, so I think, you know, good rehab is essentially following the principles of strength and conditioning, but adapting it around pain and injury. I think a lot of those principles that, you know, progressive overload of addressing individual need of all those things that we would do with strength and conditioning is often there within rehab, but it’s just adjusted to pain and pathology. So I must admit, I tend to see them overlapping a lot.

I will try and integrate some form of rehab exercises from session one. The broad question I often have in those early sessions is, are we in a phase where we’re looking really to calm symptoms down? That’s gonna be the case if they’re very irritable and easy to stir up, or are we in a phase where they can tolerate some loading and we’re looking to strengthen them up? Because that’s gonna change your exercise selection. If someone’s highly irritable,

Most of the time, we’re not going to say, right, let’s get you doing some heavy load in the gym. What we want to do is see what can you tolerate? Let’s find a starting point for you and then gradually ramp that up as your symptoms settle.

Jimmy (51:18.051)

Do you try to explain to the patient that this is often a process of trial and error where we’re kind of guessing at the front end. We’re guessing what they’re gonna tolerate and get away with. But sometimes we guess wrong.

Tom Goom (51:33.386)

Yes, yes. I don’t know if I’d use the word guess with the patient. I tend to say it’s a question of educated trial and error. So what we hope is by getting a really good subjective history, we get a really nice overview of how this person’s symptoms are affecting them, how irritable they are, which allows us then to make some good decisions with them about the starting point.

Jimmy (51:36.651)

Yeah, good point.

Tom Goom (52:00.782)

So let’s say subjectively, we’re hearing that their story is they’ve tried multiple different types of exercise and everything they’ve done has fled it up. It doesn’t take much at all to push their symptoms through the roof. So we know with that patient, from an exercise prescription point of view, we really want to start small, even if it’s at a level you think is not going to have any therapeutic value in terms of gaining strength. We really need to prioritize finding a tolerable level.

So within the session, we might look at positions they can cope with and see, can we find an exercise you can do, just one exercise, and let’s maybe do something like an isometric, if that’s better tolerated, five reps of five seconds. And let’s see how you get on with that. And with that particular patient, I’d say, can you touch base with me in a few days time once you’ve tried this? Because if you still feel that’s a bit much, we’ll dial that time back a little bit. Whereas if you feel it’s really quite manageable, we might look at dialing that time on again. Now that’s not going to get them stronger, really.

But that might, once they can tolerate it, be the start point that we progress on from. And that is very different from a patient who’s coming in and says, you know, I’m running 40 miles a week, but I get Achilles pain if I do heel sprints. Okay. Day to day, I’m really comfortable. I actually have done some calf raises already. I’m up to doing body weight in 10 kg. Completely different. Much less irritable, much more load tolerant. Okay, right. Well, you’re already at calf raises with 10 kg. Okay, what else could we bring into this mix?

So that’s where hearing the story is so important.

Jimmy (53:27.951)

Awesome. And then as you’re dosing running, is it a similar process?

Tom Goom (53:34.23)

Yeah, absolutely. So again, if their story is that they’ve had multiple attempts to return to run and every time they’ve done it, they’ve just found they’ve flared up, that person nearly always will need a slower, more gradual progression versus the runner that’s, you know, they’ve injured themselves two weeks ago, they’re already back to 5K and they’re tolerating that well. So we have to meet the runner where they’re at.

And being totally realistic, there are some runners who I have a program where they’ll get to 10 minutes of running in about five to six weeks. Now, a lot of people think of that as super, super slow, but sometimes it’s necessary. Another study that’s just come out recently, I expect you would have seen Chris Neeson’s work. They looked at using a walk-run program for people with non-specific low back pain. So the use is a treatment technique.

Jimmy (54:04.783)

Wow, yeah.

Tom Goom (54:25.078)

And what was really interesting is that they progressed through this walk run program and it seemed to improve their back pain and it changed their beliefs. They actually have more positive views of running afterwards. And they said this positive experience, it seems to be part of what drives a change. Now I mentioned this particular study because in a 12 week program, on average people reach just 2.7 kilometers for their longest run, I think it was.

Jimmy (54:51.343)

Wow.

Tom Goom (54:53.55)

So that’s being realistic, 12 weeks to get to less than 3K. Most marathon training programs are 16 weeks. So I think if people are sort of thinking, I’m not sure, like it seems to require really slow progress with this patient, that might be necessary. It might be totally appropriate if they’ve really struggled and they keep flaring up.

Jimmy (55:02.179)

Yeah.

Jimmy (55:15.799)

Yeah, it’s so much better than the alternative, which I’ve been guilty of, especially earlier in my career, which is starting, maybe you start at 30 minutes and then the next session you’re backing it up to 20 minutes. And then the next session you’re backing that up to 10 minutes and you’re just like working your way backwards, which feels defeating, frustrating, and nobody wants to be in that position.

This is a way more responsible approach. saying like, we’ll start small.

Tom Goom (55:47.394)

Yeah. And so it’s the same with running in rehab. can, you know, if you’re not sure, you can always start small because you can progress. It’s not, it’s never a problem. The patient emailing you and after run saying, do you know what? I could barely broke a sweat. got no symptoms whatsoever. I could handle that all day long. Great. We’ll do a bit more. It’s never a problem, you know, but it is hard if it’s like, you know what? That’s really stirred that knee up now. And I’m really feeling up and down the stairs and you know, three days later, it’s still really sore.

Jimmy (55:54.031)

Mm-hmm.

Jimmy (56:04.321)

Amazing. Yeah, correct.

Tom Goom (56:15.808)

Okay, right, now we need to go again. So I do think if you’re not sure, start small, you can always progress on from there. And there’s other little things you can do that sometimes help. If someone’s struggling to get past a certain distance with their training, let’s say they can cope with 5k, but whenever they push to six, it just flares them up and they feel a bit like they’re back to square one.

Sometimes actually saying, let’s plateau your training at 5K for maybe even four weeks. Let’s keep it at that level till your body gets used to it. And during that four weeks, we’ll keep, we’ll progress your rehab so you’re stronger. And then after four weeks of staying at that level, let’s see if we can nudge you up to five and a half. So rather than rushing to six and then coming back down to, don’t know, two or three, let’s keep where you are for a little bit, get your body used to it and nudge on again.

So again, instead of that rigid persistence, just demands more, it’s, okay, well, we’ve found a manageable level. Let’s stick to that for a little bit, get you a bit stronger. Let’s look for flexibility elsewhere.

Jimmy (57:21.389)

Yeah. So I guess it comes from both the therapist and the patient where as a therapist, sometimes we have to be a little bit more fluid and open to not linear progress or not just like every week being more than the last, being comfortable with that. Cause sometimes that’s hard to be comfortable with where you feel like every time you see the patient, you need to change something you need to add or you need to do more.

Tom Goom (57:49.486)

Absolutely. That is a challenge sometimes feeling that you constantly need to be pushing on. But I think we always want to keep in mind, what we want is long-term progress for people. And again, it comes back to their story. If they’ve repeatedly had flare-ups and setbacks, quite often they will come to you and say, I want to get back consistently rather than quickly. And they’ll be more happy to say, okay, yeah, let’s do this gradually. And then when they do get there, then you can keep them there, if you see what I mean.

Jimmy (58:19.503)

I do. Well, Tom, this has been great. I feel like I could go on for much longer, but I want to take up too much of your time. I really appreciate your approach. It’s very holistic. You’re taking in the patient’s story. You’re paying attention. You’re teaching us, the clinicians, to do the same with your Instagram and your blogs. So please keep doing the awesome work that you’re doing. Keep spreading knowledge and teaching and sharing with us.

You’re helping not just the clinicians, but tons of runners. So thank you.

Tom Goom (58:55.054)

Thank you very much, Jimmy. That’s very kind of you. And I’ve really enjoyed chatting. I could keep chatting all afternoon, but yeah, it’s a good place to leave it there. Thank you very much.

Jimmy (59:04.469)

Awesome. And yeah, let’s just wrap up with you one more time telling us Instagram and website.

Tom Goom (59:10.594)

Yeah, Instagram running.physio website running-physio.com.

Jimmy (59:17.615)

A little different there. Awesome. All right. And we’ll be sure to put those in the show notes. Thanks again, Tom. Really appreciate you.

Tom Goom (59:25.176)

Thanks very much, Jimmy.