E13: The impact of running shoes on injury prevention

With Jean-Francois (JF) Esculier

In this episode of Physio Insights, we sit down with physiotherapist, researcher, and educator JF Esculier to unpack what really matters when it comes to running injuries, especially knee pain.

JF shares insights from his research on patellofemoral pain, including a surprising study where education alone was just as effective as exercise and gait retraining. We dive deep into the load vs capacity concept, why your body’s “red line” is constantly changing, and how factors like sleep, stress, and life load can make or break a runner’s ability to adapt.

Key Notes

Key takeaways

Load vs capacity is the central lens. Running injuries aren’t just about mileage or pace, sleep, stress, and life load strongly influence how much training the body can tolerate.

The “red line” is dynamic. A runner’s tolerance to load shifts day-to-day and season-to-season, rising with consistent training and dropping quickly during off-seasons or periods of poor recovery.

Education-driven load management works. In patellofemoral pain, structured education alone produced outcomes comparable to adding strengthening or gait retraining.

Effective education is specific. Pain ≤2/10 during runs, return to baseline within ~1 hour, no worsening the next morning, and smarter distribution of volume (run more often, less per session).

The 10% rule isn’t evidence-based. Rigid weekly limits don’t reflect how real training works; periodized builds with down weeks and “next reasonable steps” are more practical.

Gait and footwear are tools, not defaults. Gait changes and shoe selection are most useful for persistent or recurrent issues when the goal is to reduce tissue load, not to “fix” a runner.

Capacity is under-measured in research. Most studies ignore sleep, stress, and hormonal factors, limiting how well research translates to real-world injury prevention.

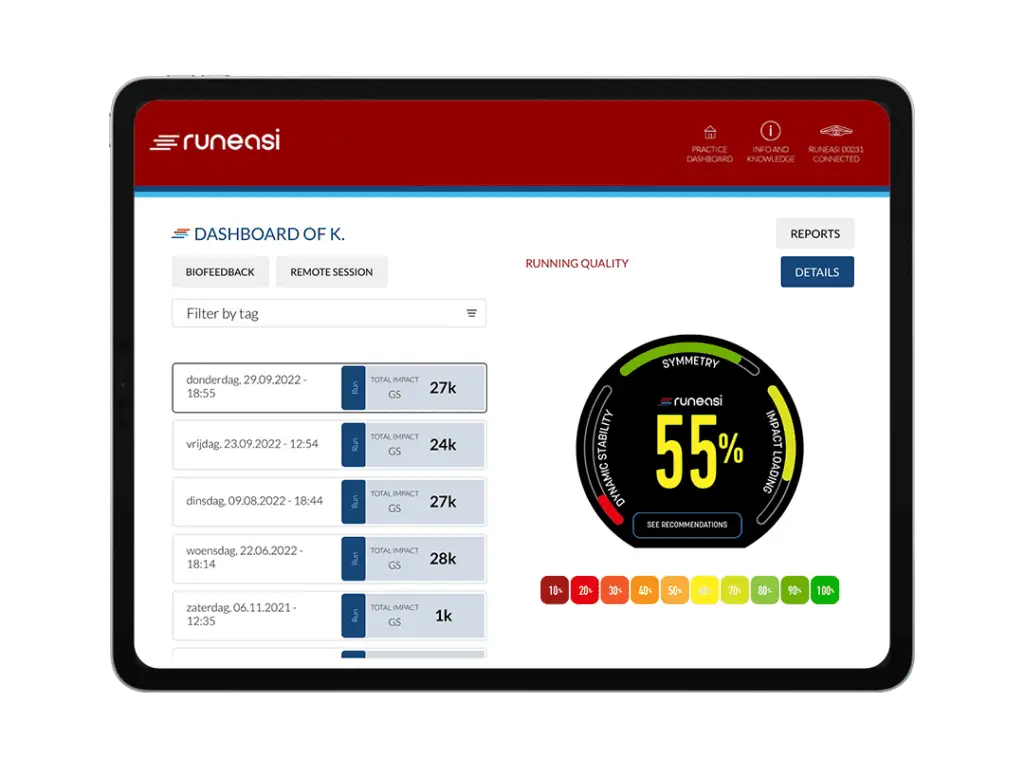

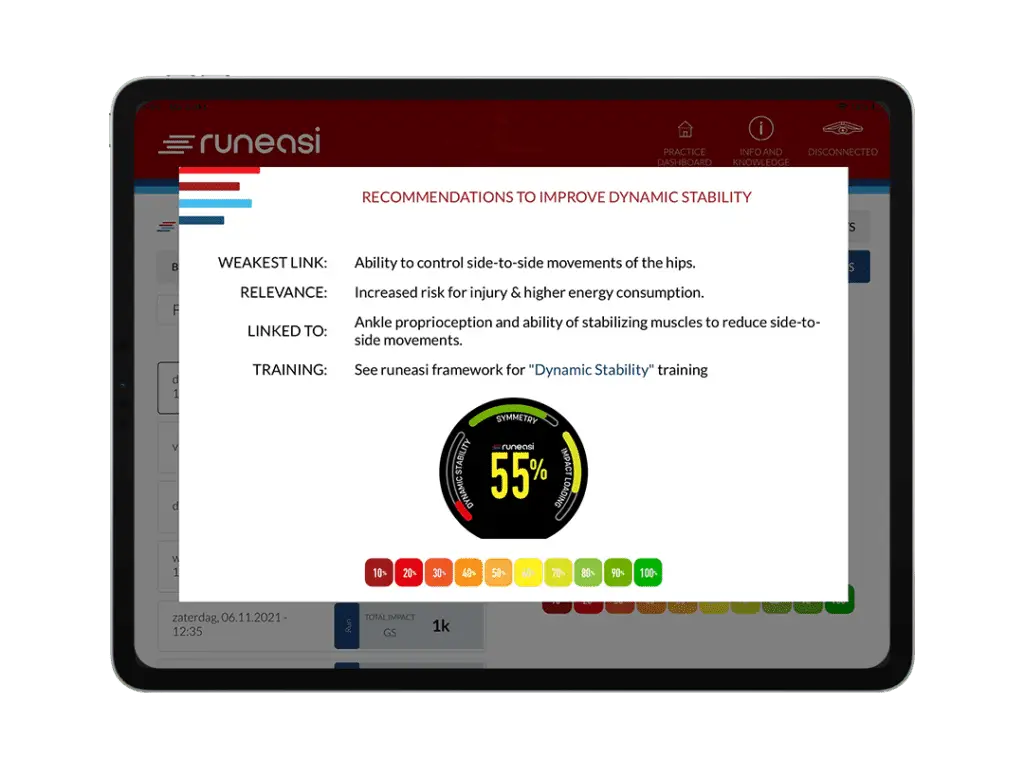

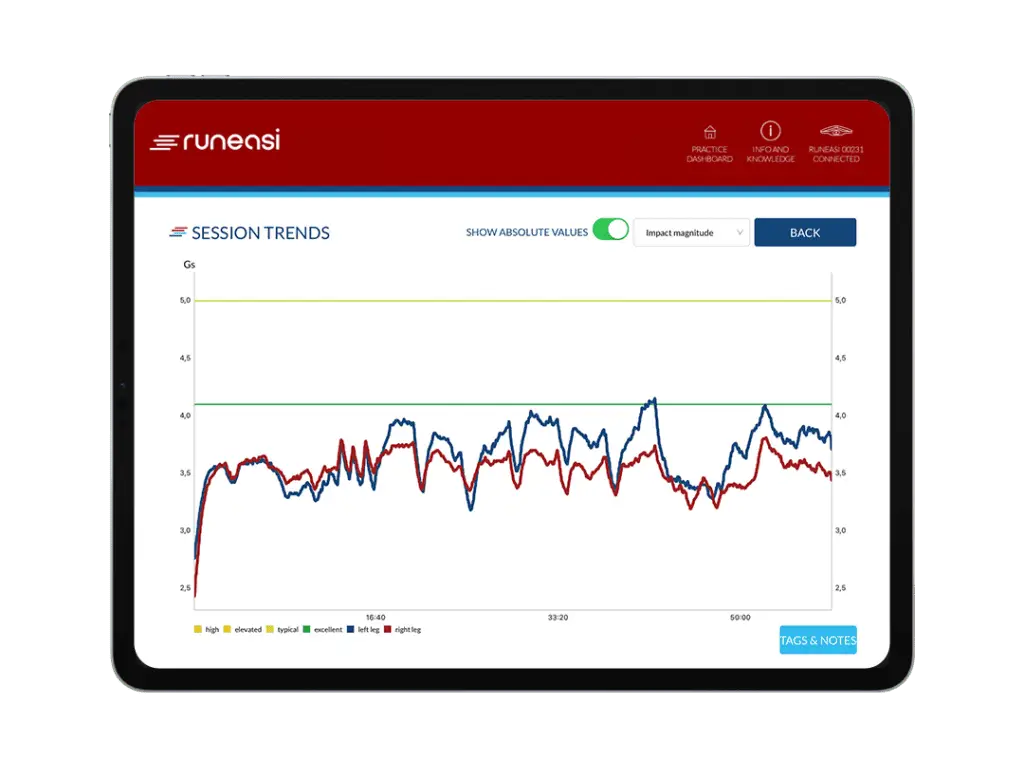

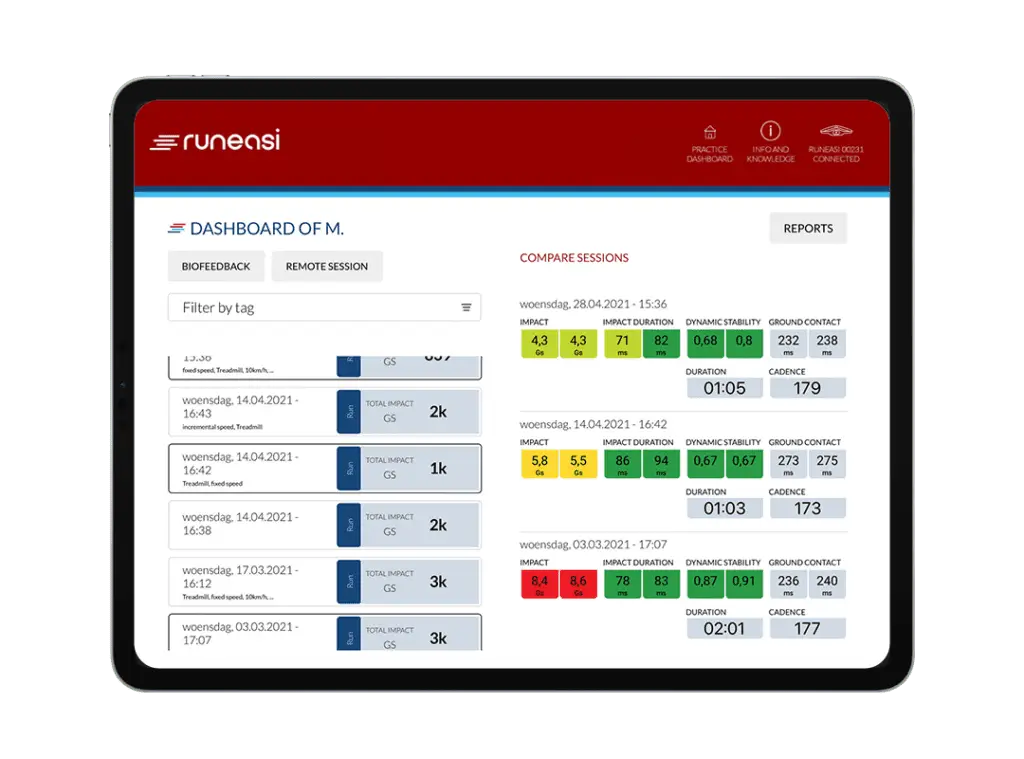

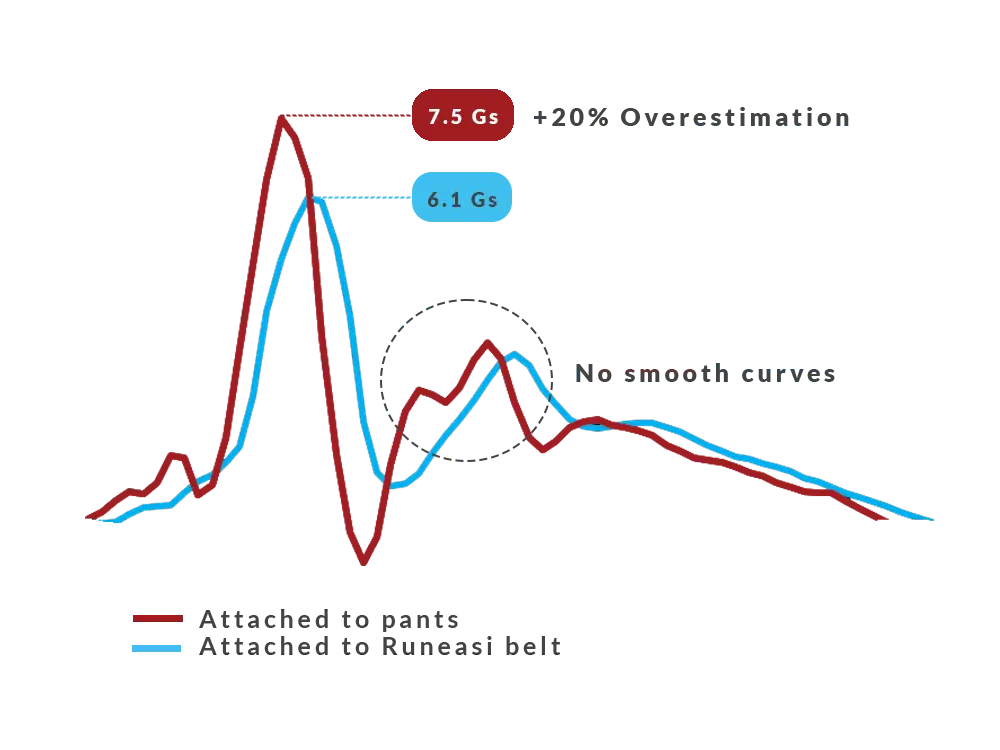

Objective data can build confidence. Tools like Runeasi help quantify impact, symmetry, and readiness, especially in return-to-run decisions after major injury or surgery.

Full Audio Transcript

00:00:07.040 –> 00:00:33.970

<v Jimmy>Welcome to the Physio Insights podcast presented by Runeasi. I’ll be your host, doctor Jimmy Picard. I’m a physical therapist, running coach, and team member here at RUNNES. On this show, we have real conversations with leading experts, digging into how we recover from injuries, train smarter, and use data to better guide care. Whether you’re a clinician, coach, or an athlete, we’re here to explore what really matters in rehab and performance.

00:00:34.450 –> 00:00:41.810

Let’s dive in. All right, JF. Welcome to the Physio Insights podcast. Great to have you here today.

00:00:42.405 –> 00:00:44.805

<v JF>Thanks, Jimmy, for your invite. I’m happy to be here.

00:00:44.805 –> 00:00:54.885

<v Jimmy>Great. So I’ve been following your work for quite some time with the Runner’s Clinic and then your Instagram. But for those listeners who don’t know of you or on our way of you, can you give us a quick little background?

00:00:55.410 –> 00:02:02.820

<v JF>Yeah. I’ll just start by saying I wear three different hats, and that’s being a clinician, being a researcher, and being an educator. So I, been a physiotherapist now for sixteen years, and I started working in the clinic full time and then I just had too many questions trying to find the answers in the literature, couldn’t find them and that’s how I decided to get involved in the research at that point. So I got involved doing a master’s and a PhD on patellofemoral pain and runners and then I moved after that I’m from Quebec City so I did that research over there at Laval University and then I moved out west in Western Canada University of British Columbia to do a postdoctoral fellowship on basically answering the question is running bad for your knees because I was getting that question all the time from my patients and I wanted to, study running and, knee osteoarthritis and during that whole time I remained the clinician working part time in the clinic and also did a lot of teaching through the running clinic. So continuing education courses, traveling around the world, teaching best practice, latest evidence about running injury prevention and treatment.

00:02:02.820 –> 00:02:06.340

So that’s pretty much what I do as a as a combination there.

00:02:06.765 –> 00:02:10.925

<v Jimmy>Where did your passion for running start? Are you were you a runner growing up?

00:02:11.405 –> 00:02:22.150

<v JF>A good question. No, I was not. I I was actually, I wouldn’t run unless I had a ball to run for. So I was a I was a soccer player. I used to play just for fun.

00:02:22.150 –> 00:02:39.905

I wasn’t a competitive player or anything. And I played until the end of my university in physiotherapy school. And I started running without a ball when I started being a physio, simply because I couldn’t really be part of a team anymore. I was working evenings. I was working weekends with teams as a physio, and so I just started running.

00:02:40.145 –> 00:02:56.180

And I was strongly influenced by the clinic in which I started working as well as a physio in Quebec City, and that’s a clinic founded by Blaise Dubois, who is the the founder of the running clinic. Yeah. So that’s how we got in touch and, and I started being involved with the running clinic as well.

00:02:56.260 –> 00:03:00.420

<v Jimmy>Awesome. And so then you you just fell in love with running as well, like, personally?

00:03:00.875 –> 00:03:04.635

<v JF>Absolutely. And since then, I I mean, I started on the road like most people do.

00:03:04.635 –> 00:03:04.955

<v Jimmy>Yeah.

00:03:04.955 –> 00:03:26.170

<v JF>I ran all the distances on the road up to the marathon, and and I I really enjoy the trails now. So I’ve been dabbling a little bit more with the longer distance is on the trail. Well, I mean, longer, everything is relative, but I’ve done a few, 50 k races. I’ve done up to 87 k, race on the trails. I I really enjoy that.

00:03:26.170 –> 00:03:31.215

It’s it’s I feel like it’s much more fun. I like the variety of it and the nature part of it.

00:03:31.215 –> 00:03:38.815

<v Jimmy>But Yeah. Awesome. No. I’m with my background is running. I was a runner growing up, but in my thirties, starting to get into trail running.

00:03:38.815 –> 00:03:55.680

It seems like it had a big boom in the past ten years or so, and I rode the boom as well. And so, yeah, I I can, relate to your love of the trails. Moving in the mountains is awesome. So then right now, you kind of you described yourself wearing three hats. What is your primary hat right now?

00:03:56.245 –> 00:04:20.440

<v JF>Primary hat right now is the clinic. So I work as a clinician three days a week with, with patients. And I do one day of research and teaching typically and one day of, more admin mentorship through, our clinic with our younger physios. So primarily a clinician, but I am really trying hard to keep those three hats on. It’s not easy.

00:04:20.760 –> 00:04:32.975

Takes a lot of time and effort and energy, but I I really enjoy how all three of them can help, you know, the the other two basically. Every single aspect helps the other two. So Yeah. I really enjoy the combination.

00:04:33.215 –> 00:05:07.445

<v Jimmy>No. That’s awesome. And, yeah, I think the reason I wanted to have you on is because because of that combination, you bring this unique perspective where not only have you been in the research world asking tough questions, trying to answer them, you’re in the trenches with us clinicians dealing with patients and putting the research to the test. So it brings a good starting point for us to start talking about something I was interested in hearing you explain a little bit more. And that’s this idea of load versus capacity and how we talk to patients and how do you present that in the clinic.

00:05:07.845 –> 00:05:08.245

Mhmm.

00:05:08.245 –> 00:05:38.215

<v JF>Yeah. And it’s, such a great question, Jimmy, because the whole load versus capacity concept is a bit blurry in a way, simply because it’s it’s so hard to measure. So I like to explain it clinically with visual tools, one of them being the mechanical stress quantification that we produce with the running clinic. That’s a visual tool that I show my patients very often. And it just shows how basically your body will adapt, but as long as the applied stress is not greater than its capacity to adapt.

00:05:38.310 –> 00:06:36.380

So the load itself, so that load component is, say, you’re a runner, that’s how much you’re running, that’s how fast you’re running, that’s the hills, that’s all these aspects that will influence how your tissues or what forces will be applied on your tissues. But then even if you control everything on the load side of things, there’s the capacity side that we can’t forget about and that’s dictating how well your body will be able to to tolerate that load and that’s the sleep, the stress, anxiety, just life stuff. And I’m sure listeners will will, relate to that but sometimes you you just, you know, you’re tired, you worked hard, you had a stressful day, things are not going great in your life and you’re just going for an easy run, a run that you would normally tolerate very well and things start hurting. And that’s just a reminder of, yeah, it’s not just about load. Like your body can sometimes very well tolerate that load, but the capacity side is so important.

00:06:36.380 –> 00:06:48.620

So what I explain to my patients is is that it’s a having the right balance between those two very important components to maximize their adaptation and their ability to, increase their training if that’s what they want to do.

00:06:48.755 –> 00:07:03.555

<v Jimmy>Yeah. And so when you’re when you’re using this diagram or visual to help educate, the first thing I it made me think about was Scott Dye’s, like, tissue homeostasis or the envelope of function. Is it is your your tool similar to that with, like, something like that?

00:07:03.980 –> 00:07:27.635

<v JF>Yep. The Scott Dye came up with that in 1996, I believe. So it’s it’s a similar concept. The visual is a bit different in the sense that we we try to show that if you load up regularly, you you can actually change the location of that envelope of function or that red line. And we call it the red line because it’s it’s the maximum capacity of your body to tolerate that load.

00:07:27.635 –> 00:08:08.150

So that red line can go up, it can go down, it will be different today versus tomorrow based on life things. So the the tool that we created is a bit more dynamic in that sense and it also shows that you need to reach a certain level, a certain threshold to trigger these adaptations. And that becomes useful when, say, someone is taking an off season and they were they ran a marathon in October, say in Chicago, and then they take an off season and then they go back to running in in January. But because they didn’t load anything, their red line went down, and they need to start gradually. So we need to maintain a certain threshold to maintain these adaptations in our body.

00:08:08.470 –> 00:08:40.390

<v Jimmy>Yeah. Something you said at the beginning there about that red line being dynamic and that it fluctuates even as in a short of windows like day to day and things like sleep, stress, all of that plays a role. I feel like it makes sense and patients have a can grasp with like the off season, hey, I’m deconditioned, I’m out of shape, it makes sense that my red line has gone down. How do you help those folks that maybe are pushing back with stress or lack decreased sleep and they don’t see that that’s important? How do you help them with that?

00:08:40.955 –> 00:08:56.840

<v JF>That’s hard. Right? I’m sure everyone who’s listening to this can think of of some patients specifically who are who are pushing back on that. And, you know, I I see myself as as a physiotherapist. I see myself as a guide in the sense that I am explaining things to people.

00:08:56.840 –> 00:09:16.975

I’m giving them the pros and the cons and suggesting different approaches and then they can make their own decision. Do they want to keep pushing through this? That’s their call in the end, unless there’s, say, a high risk bone stress reaction, bone stress like a stress fracture, then we can’t push through this. And I’ll I’ll be a bit more, insistent on the fact that they they shouldn’t push through it. But it’s hard.

00:09:16.975 –> 00:09:29.920

Like, I try to give them examples. I try to to show them that, you know, sometimes your body is just sending you messages like that red line. You need to listen to it. And if you don’t, you might have a rough season. You can’t perform well.

00:09:29.920 –> 00:10:02.380

If your goal is to run well, to improve your personal best, to to just gradually progress as a runner, you can’t push through pain. Like, you can’t perform well when it’s painful. And sometimes that will resonate with people well too if their goal is that. Now I’ve seen people who are going through a divorce or people who are going through a tough time in their life and they’re just running for their mental health and they just wanna stay active. And they’re they’re open to feeling a bit more symptoms, a bit more pain because they still get their mental health fix.

00:10:02.380 –> 00:10:09.820

Yeah. So like different situations where I think we need to be flexible as as health care professionals and explain things well.

00:10:10.115 –> 00:10:34.920

<v Jimmy>Yeah, sometimes you’re willing to accept the trade offs of pushing through when maybe you shouldn’t because mental health, whatever it is. So you did a great study with patellofemoral pain that looked at education versus education plus exercise versus education plus strength. Could you talk a little bit about just like that study in general and then we’ll hone in on the education that you did as well?

00:10:35.485 –> 00:10:55.780

<v JF>Yeah. Absolutely. So the three groups, education only, like the well, the first one is education only, but everyone was getting that same piece of education that we’ll we’ll touch on after. And that was our control group, basically. At first, when we submitted the study to ethics, we had a real control group that was doing nothing.

00:10:55.780 –> 00:11:16.725

But given the strength of evidence on the benefits of strengthening, benefits of so many different interventions for catellofemoral pain, the research, ethics committee said, well, we’d prefer if your control group has some sort of intervention. Find it we think it’s more ethical to to give them something. So that’s why we came up with that education piece, which became our control group in the end.

00:11:16.725 –> 00:11:20.005

<v Jimmy>And it seems like that actually has really strengthened the study too.

00:11:20.420 –> 00:11:48.870

<v JF>I think so. It was an interesting suggestion from the ethics committee, and, I am happy we did it in the end. In an ideal world, we would have had a fourth group that’s a real control, but, like, it just adds so much in terms of, of logistics and whatnot. But that second group had the same education in an exercise program that was targeting strengthening of quadriceps, hips, core muscles, just like the latest research would suggest. And then the third group was the same education plus gait retraining, gait modifications.

00:11:48.870 –> 00:12:10.165

So we were asking people to increase their cadence, try to run softer, no change in shoes, but potentially changing foot strike pattern as a last last resort, which we did not end up doing with any of those participants. The goal was to remove or not remove, I should say, reduce the load on the patellofemoral joint when running in that third group.

00:12:10.165 –> 00:12:31.735

<v Jimmy>With the third group. Yeah. And so you picked those two groups because it seems like as a profession, when we look at patellofemoral pain, we think of or traditionally we think of faulty movement patterns or loading, we need to strengthen stuff to improve the biomechanics And then gait retraining, similar attitude, but also to unload the tissue. Is that right?

00:12:32.055 –> 00:12:51.360

<v JF>Yeah. Pretty much. I mean, we bring it back to that load capacity concept, in a way, the exercise strengthening exercise approach is trying to to increase the capacity of your knee, of your legs to tolerate the load. And the third group was to reduce the load a bit more in your joints to be able to handle running better.

00:12:51.360 –> 00:13:12.370

<v Jimmy>What was really interesting in this study was that you showed that when we strengthen areas, people get stronger. When we gait retrain, we can actually manipulate and change people’s gait. We can like you did what you wanted to do. But then the interesting thing was all three groups got better, right, at eight weeks and twenty weeks, I believe. Is that right?

00:13:12.370 –> 00:13:12.850

Correct.

00:13:12.850 –> 00:13:13.090

<v JF>Yes.

00:13:13.090 –> 00:13:18.930

<v Jimmy>Yeah. So the common thread throughout them being the education. So let’s talk about the education and what that looked like.

00:13:19.090 –> 00:13:43.320

<v JF>Yeah. And to be honest, I was surprised by the results. That that was not our hypothesis initially. Right? We thought that maybe all three groups would improve, but we thought that the group where we added strengthening and the group where we added gait retraining would improve better, improve more, and the group in which we added gait retraining would improve faster because we’re reducing load and they just get better faster.

00:13:43.320 –> 00:14:06.285

And like you said, Jimmy, like all three groups improve exactly the same in the end. So that that piece about education is is probably the the main take home. Like, what should we be using with those people as priority in the clinic? Well, the key pieces of advice there were to, first of all, listen to your body. So that red line, make sure you don’t go past it two out of 10 pain when you run.

00:14:06.285 –> 00:14:29.645

So during running, and it had to go back to pre running level within an hour after you’re done. So say your pre your baseline is you don’t feel it at rest, you go for a run, it goes up to two out of 10. That’s fine. As long as it’s back to zero out of 10 within an hour after you’re done. We also said no increase the next day when you get up in the morning, which is a typical sign of joint overload.

00:14:29.645 –> 00:14:58.165

And then we we help them to build their running program or to tweak their running program, I should say, by making them running more often less at a time. Example, if you’re someone who runs three times 10 kilometers per week, would make you run five times a week instead but shorter distances. So it could be a five times six k, could be a different split. I’m just giving a simple example here, but running more often less at a time. We also told him to run slightly slower.

00:14:58.405 –> 00:15:27.885

It’s not a ton slower necessarily, but say thirty seconds per kilometer slower, which again is accepted by most people as a way to to reduce load a bit. And then we recommended that they could do some run walk in there as well, but keeping the overall volume or focusing on volume. Avoid the hills and avoid stairs running because the project was done in Quebec City. There’s a lot of stairs. There’s even a race around the old town where you have to go through all the different staircases.

00:15:27.885 –> 00:15:28.285

<v Jimmy>Nice.

00:15:28.660 –> 00:15:55.115

<v JF>So it’s a it’s a common thing for people there to run-in stairs. So avoiding that and that’s pretty much it. And and those like, in that intervention, say in the control group, the education only group, people were meeting with the physio five times over eight weeks. They were not being touched or anything. They were just looking at their program, talking about their symptoms, how the last few training sessions went and adjusting the next progression.

00:15:55.115 –> 00:16:01.770

So adding more volume typically as a first step. Eventually, when things got better, adding more speed and then adding the hills back.

00:16:01.850 –> 00:16:06.730

<v Jimmy>Yeah. So it sounds like very structured load management advice.

00:16:07.050 –> 00:16:15.445

<v JF>Absolutely. Yeah. That was the the whole point. And we we trained our physios because I was the blinded assessor in the whole project. I didn’t know which group people were assigned to.

00:16:15.445 –> 00:16:29.610

I was measuring everyone in the lab. I was taking all the questionnaire data and all that stuff. So my colleagues at the clinic were providing the interventions and we trained them really well so they could provide the best education possible.

00:16:29.610 –> 00:16:46.645

<v Jimmy>Yeah. And it sounds awesome. So then what is your takeaway with this where education by itself kinda takes the pressure off of us PTs a little bit. We can just get really good at this. And then how do we square this with, like, do we still should we still be strengthening?

00:16:46.645 –> 00:16:51.045

Should we still be making gait modifications, or should this be the focus of what we do?

00:16:51.440 –> 00:17:05.565

<v JF>Such a great question, Jimmy. I I think the main take home message is we should prioritize that education piece. Does it mean that we should not recommend strengthening? No. Does it mean that we should avoid the gait retraining because it doesn’t add any value?

00:17:05.565 –> 00:17:25.260

No. I still do those things in the clinic on a daily basis. We stopped the follow-up at five months. So the intervention itself was two months, eight weeks. And then we had people fill out the questionnaires on symptoms and function at the five month mark so three months after we ended the intervention and at that point all groups were still improved just the same.

00:17:25.260 –> 00:18:05.565

In an ideal world we would have had another follow-up maybe at one year maybe at two years just to see if there’s any difference in terms of recurring like recurring pain recurrence rates. We don’t have that data. My personal bias is that maybe we can help because we’re adding more capacity to the system with the strengthening because we’re reducing load, maybe allowing an easier increase in volume in people who change how they run. I don’t have the answer to that unfortunately. I still do those things in the clinic reinforced I think, my bias at least or my preference for the educational piece as a key, like, first thing to do with everyone.

00:18:05.805 –> 00:18:16.650

<v Jimmy>Yeah. So maybe for the listeners and for me personally too, it’d be interesting to hear when you see a runner patellofemoral pain, like, the first visit, what does that look like for you?

00:18:16.650 –> 00:18:58.435

<v JF>First of all, I take one hour to assess everyone because I like to talk to them, and there’s a lot of talking going on in there. So there’s obviously the the initial assessment, history taking subjective objective and after that usually I have about half an hour left which means I’m going to explain what patellofemoral pain is to them. It’s an irritation between your kneecap and the femur underneath. Every time you do activities that involve contracting your quadriceps with your knee bent, you are compressing those two bones together. That’s how it should be, but there’s an irritation behind it and that’s why you’re feeling pain so we need to change a few things in order for your bones and and your your joint to get better.

00:18:58.435 –> 00:19:25.615

So that’s the main part of my explanation usually and I give them the options but I always write down a plan I always send a pdf plan to everyone I see the number one on my plan there’s their name at the top underneath it says say patellofemoral pain I write the date and I write load management And that’s the educational piece. What’s the maximum level of symptoms you should tolerate? What’s too much? Where’s that red line? And then how to change that?

00:19:25.615 –> 00:19:35.570

How to address that in your training? What do you do you run more often less at a time? Do you cut down on the hills? And that depends on your situation. Do you have a race coming up?

00:19:35.570 –> 00:19:50.285

Are we trying to keep some volume? Do you have nothing going on? And we have more freedom to reduce load in the short term. So there’s that whole piece of personalization that we do. And then after that, usually I’ll give them an exercise, maybe two.

00:19:50.605 –> 00:19:59.820

They will typically not assess their running gait on the first visit because we focus on these these first two things.

00:19:59.820 –> 00:20:00.060

<v Jimmy>Mhmm.

00:20:00.060 –> 00:20:20.485

<v JF>So usually, I’ll tell them next time, bring in your shoes. We’ll look at your your gait on the treadmill. We’ll see if there’s any tweaks that we can make to help you progress better, to help you reduce load and so on. And we address the capacity side obviously too with just asking about sleep, which I think is as physios we tend to forget about too often. So how’s your sleep?

00:20:20.485 –> 00:20:25.925

How’s your life? Is there anything there that, we need to consider in the whole load capacity balance?

00:20:26.530 –> 00:20:46.025

<v Jimmy>Yeah. So it sounds like a lot of giving them ownership a little bit of self managing with some rules or guidelines from you, like you said, as the guide for the for the patient through their journey, getting back to full steam running. Yeah. Love that. I really like that point about not trying to cram everything into that first session.

00:20:46.025 –> 00:20:54.745

It’s like, yeah, you throw a gait assessment into that. You’re gonna in one hour, you’re gonna run out of time and you’re gonna be scrambling. And I’m sure the education will suffer.

00:20:55.020 –> 00:21:02.620

<v JF>Oh, yeah. Absolutely. So it’s really a matter of priorities to me. What’s what’s the number one? And also what are the expectations of the person?

00:21:02.620 –> 00:21:16.095

Right? I always ask them, what are you hoping to get from me? Yeah. And sometimes the first thing they say is, I’d like you to look at my running. And instead of giving them exercises on the first visit, I’ll tell them, we’ll do just a quick check.

00:21:16.095 –> 00:21:29.330

We’ll still do the education part, but we’ll do a quick check on the treadmill. And sometimes I’ll I’ll tell them, okay, like, maybe change this, change that for now, but last time, let’s do a more in-depth analysis and see if we change anything more.

00:21:29.330 –> 00:21:42.965

<v Jimmy>Yeah. I love it. It’s nice to hear somebody of your caliber still, like, splitting things up and, like, for younger clinicians especially, taking some pressure off, not trying to do it all in one setting and, like, you multiple sessions for a reason, right?

00:21:42.965 –> 00:21:45.685

<v JF>Yep, absolutely. So if we zoom in

00:21:45.685 –> 00:22:03.200

<v Jimmy>a little bit on this this initial eval, as we’re discussing with a runner training parameters, You were involved in a good systematic review looking at various running or training parameters and injury, running related injuries. Can you tell us a

00:22:03.200 –> 00:22:18.905

<v JF>little bit about that? Another study that gave us results that are a bit surprising and that raise more questions. So that systematic review we published in the Journal of Athletic Training a few years ago, think it was, ’21 or something.

00:22:19.200 –> 00:22:23.200

<v Jimmy>And it’s open access, so anyone, I believe, who can can get in there and read it. Yeah.

00:22:23.200 –> 00:22:38.785

<v JF>Yep. It is. So what we, what we did in that systematic review was to look at two things. First of all, is there an association between training parameters in runners and injuries? So for example, volume or speed or or hills or anything like that.

00:22:38.945 –> 00:23:21.180

And then the second objective was looking at changes in these parameters and how that might influence injury risk. So basically, we looked at all the literature on, on these studies that assessed running population injuries and a running program of some sort, and that’s where you open a can of worms. So the main results of the study first of all was that training parameters don’t seem to be associated as a whole with running injuries, so that was one of the key findings, but also that training changes in training parameters were not consistently associated with injuries either. And that’s also something that’s surprising when you read that because as clinicians, that’s not what we notice. Right?

00:23:21.180 –> 00:23:30.415

<v Jimmy>So are there a few of these parameters off the top of your head where you were most shocked about that you saw? You thought for sure there’d be an association here and there just wasn’t?

00:23:30.655 –> 00:23:53.200

<v JF>Yeah. You know, I I for sure thought that, you know, increasing speed work would lead to injuries. It’s clinically speaking, that’s the main culprit that I see. People adding speed intervals, people adding, you know, working out at a track with, with the running club or whatever training for an event and just pushing a bit more. So speed for me is the number one on my list usually.

00:23:53.200 –> 00:24:09.930

Like, adding volume is also important, but speed tends to be, higher on the list. So I was expecting to see more of that. But there are so many limitations in the studies, which I’m sure you’ll want to talk about Sure. That probably explain why we didn’t find any any association there.

00:24:09.930 –> 00:24:19.530

<v Jimmy>Because like, yeah, you read that study and you could say like, oh, I don’t need to ask questions about training parameters because this study showed no association. But yeah. How how do you explain it?

00:24:19.530 –> 00:24:39.890

<v JF>Yeah. I mean, clinically speaking, like if we if we just put the study aside for for a second, I always ask people in my history taking, did you change anything recently in your training? And I’m sure most people will relate to that too. And and the answer most of the time is is, yeah, I’m training for something. I’m increasing my volume.

00:24:39.890 –> 00:24:49.650

I added speed work. And sometimes the answer will be no. And then I ask all these questions one by one. Did you increase your volume recently? Did you add more speed work?

00:24:49.650 –> 00:25:03.765

Did you add more hills? Are you training for something? And then usually something will come up. Right? So in those studies, the main limitations that we outlined in the discussion of the article, if people wanna to dive a bit deeper and then it’s it’s discussed, at length there.

00:25:03.765 –> 00:25:16.420

But, first of all, the definition of an injury is an issue. You know, what is a running injury? And if you ask hundreds or even thousands of runners, what is an injury for you? And everyone will have some sort of a different answer.

00:25:16.500 –> 00:25:18.260

<v Jimmy>Yeah. So how do you define it?

00:25:18.260 –> 00:25:26.305

<v JF>How do I define it myself is different because I understand the body maybe a bit more than my patients do.

00:25:26.305 –> 00:25:26.865

<v Jimmy>Mhmm.

00:25:27.025 –> 00:25:52.895

<v JF>So for me as a runner, like, if I feel a little bit of pain in some areas, but I know that it’s linked to, for example, sleeping less, more stress, I’m not worried about it. For me, it’s not an injury. But I know I’ll need to adjust my training accordingly and it will get better very fast. For some people, it might be as soon as I feel pain, it’s an injury. For some others, might be it doesn’t matter how painful it is.

00:25:52.895 –> 00:26:22.055

As long as I can run, I am not injured. Right? You know, what we found out in that systematic review is different studies use different definitions and that influences the outcomes like who got injured in that study. Well, it might have been different if they use a different definition. So it’s really hard to pool and combine all these studies together and come up with some sort of clear results, clear findings, and recommendations because of the limitations of the included studies.

00:26:22.135 –> 00:27:00.060

That’s factor number one. Factor number two is, the fact that a lot of those studies for example, they might have looked at increasing volume or or like if you run four times a week versus twice a week, is there a difference in injury rates? And instead of doing, say, modulated program or more like a normal looking training program, they would compare four times one hour of running with two times one hour of running who will get more injured. Yeah. My personal view or advice clinically would be, well, maybe you can have those two one hour, runs, but your other two should be probably shorter.

00:27:00.140 –> 00:27:11.100

Like, they could be fifteen minutes, thirty minutes, whatever. But you can’t compare two times one hour with four times one hour and assume that’s the way to go. Like, to me, it’s it doesn’t make much sense.

00:27:11.565 –> 00:27:15.405

<v Jimmy>Were there any more limitations you can think of off your top of your head or leave it there?

00:27:15.725 –> 00:27:34.940

<v JF>One more. No one really looked at the capacity side of things. No one asked about sleep, about stress, about even hormonal cycle in female runners. Yeah. Just that whole body side of things, capacity side was completely ignored by about ninety five percent of the studies.

00:27:34.940 –> 00:27:35.740

<v Jimmy>Interesting.

00:27:35.900 –> 00:27:45.345

<v JF>So to me, it does not help us clinically to just look at the load. Yeah. We need to make sure we consider the capacity side.

00:27:45.345 –> 00:27:50.945

<v Jimmy>Do you feel like this is a missing link generally speaking for physio research?

00:27:51.370 –> 00:27:58.410

<v JF>Absolutely. But you know what, Jimmy? It’s so hard to assess. It’s it’s just so hard to measure in the end. Yeah.

00:27:58.490 –> 00:28:07.735

We don’t have a clear questionnaire as far as I know that would just capture all these things together. So that means you have to ask a bunch of specific questions.

00:28:07.735 –> 00:28:21.015

<v Jimmy>Yeah. Because there’s so many things that contribute. It’s it’s can be a bit overwhelming. I’m thinking of, I was recently looking at I think it was Alison Gerber’s study on standing and the loads on the knee. Are you familiar with this one?

00:28:21.420 –> 00:28:23.500

<v JF>Not that one specifically. Not on standing.

00:28:23.500 –> 00:28:54.380

<v Jimmy>I think I believe she looked at, like, just with this the rise of standing desks and people switching from, like, with sittings and new smoking. I believe it was something like standing for eight hours a day is equivalent joint loads for the knee as running a marathon. So like, Yeah, like we wouldn’t think of that load as being problematic. But for if you’re got a sensitive cranky knee, and I’m standing all day on it, maybe that’s something I need to consider. But again, it just speaks to like, how like there’s just so many different variables here to think about.

00:28:54.700 –> 00:29:06.515

So if we go back to this study and the training parameters, how with the results that we saw and the limitations you described, how do we take this into the clinic and what do we do with it?

00:29:06.515 –> 00:29:28.360

<v JF>It’s a tricky question. Well, first of all, the ten percent rule, don’t increase by more than 10% a week is not based on any solid research. I never really use that with with my patients. So I would tell clinicians don’t use that. It’s more because if you run, say, 12 kilometers a week and you increase by 10%, you’re it’s gonna take you forever to train for a half marathon.

00:29:28.360 –> 00:29:28.600

Right?

00:29:28.600 –> 00:29:35.225

<v Jimmy>Yep. Yep. And, like, yeah, when I was in college running in college, we ran 100 mile weeks and, yeah, it’s like Yeah. Not happening.

00:29:35.225 –> 00:29:54.550

<v JF>Oh, yeah. That’s way too much. So the the high volume and the low volume, it doesn’t work. Maybe in the middle, it could be it could be an interesting piece of general advice, but at the same time, as health care professionals who might be recommending more personalized options to people, I think we can do way better than that. So I don’t tend to go with that 10%.

00:29:54.550 –> 00:30:02.795

I tend to recommend people that they use a more of a periodized training structure or schedule.

00:30:02.875 –> 00:30:03.035

<v Jimmy>Mhmm.

00:30:03.035 –> 00:30:17.900

<v JF>So basically what that means is don’t increase increase increase increase increase increase every week. Yep. Try to have cycles, for example, two weeks or three weeks of build Yep. Then one down week, one rest week to allow the body to recover.

00:30:17.900 –> 00:30:32.475

<v Jimmy>Yeah, tell folks I want there when I zoom out, I want it to look like a roller coaster where it’s like gradually going up. Yeah. Yeah. Do we have research to support that? Is there is there anything out there that says like there we will reduce injury risk by doing that?

00:30:32.475 –> 00:30:33.835

I know we do it.

00:30:33.915 –> 00:30:36.475

<v JF>Mhmm. And not as far as I know.

00:30:36.475 –> 00:30:36.635

<v Jimmy>Yeah.

00:30:36.635 –> 00:30:45.110

<v JF>And and that’s the art of it. Right? Yeah. It’s really hard to have strong signs to guide everything that we do. Mhmm.

00:30:45.350 –> 00:31:18.580

And as far as I know, there’s nothing on that. I mean, there was that study that came out, that said, don’t increase your long run by more than 10% week, which there’s there’s so many limitations to that. Like, if you do that, you will never ever be able to build up for a half marathon or a marathon, in my opinion. Yeah. Simply because a normal half marathon training program, if I’m talking kilometers, will typically go long run 12 k, next weekend could be 14 and then 16.

00:31:18.580 –> 00:31:25.460

You’re already above that 10%. Yeah. And that’s a normal training program. Yeah. There’s nothing wrong with that.

00:31:25.460 –> 00:31:47.380

So I, you know, I I I don’t think numbers, general numbers will give us a lot of information as clinicians. It’s really practicing, it’s gaining more experience, going more conservative with people, make sure they have a structure, listen to what they say, where’s that red line for them, and build accordingly. That’s I think that’s the best we can do.

00:31:47.380 –> 00:31:53.965

<v Jimmy>Yeah. I like that. There’s a running coach here in The US, Steve Magnus. Are you familiar with Steve Magnus? Yes.

00:31:53.965 –> 00:32:17.860

I recently heard him on his YouTube channel talking about as progressing athletes through a a cycle. He’s like, just ask yourself, like, what’s the next reasonable step? And it’s like, let’s just be reasonable. And I think anecdotally, yeah, you look at the patients we see and most of the time it was there was something that was just like unreasonable. It was just different and unreasonable for what they were ready for.

00:32:17.860 –> 00:32:44.480

It goes back to that load versus capacity idea. Absolutely. I’d like to take a moment to thank our sponsor, Runeasi. Runeasi is a running and jumping analysis tool that helps provide objective data on things like impact loading, dynamic stability, and symmetry. I’ve been using it in the clinic for the past three years and I love how easy it is to add to my evaluations.

00:32:44.800 –> 00:33:03.425

Not only that, but it backs up my clinical reasoning and helps me with my decision making process when I’m doing exercise prescription. So if you’re a physical therapist or running coach, head on over to runeasi.ai and book a demo. If you’re lucky, it will be with me. Awesome. No.

00:33:03.425 –> 00:33:11.880

That’s great. So anything else from this specific study that you’re still that you’re taking in the clinic and using as education or anything like that?

00:33:12.040 –> 00:33:29.415

<v JF>No. I think those like, that usually covers, most of it. Like, key pieces of advice for me, like, if you’re a new runner, don’t run a marathon the first year Mhmm. Which is not discussed in the article. But in terms of load versus capacity versus how quickly you increase the load, it doesn’t make any sense.

00:33:29.415 –> 00:33:46.700

So usually, I’ll tell people the first year you can do like, a 10 k is obviously entirely feasible. A half marathon is feasible in the second half of the year Yeah. For most people. And then a marathon, you shouldn’t consider the first year should be the second year, maybe even third year depending on your goals.

00:33:46.925 –> 00:34:04.340

<v Jimmy>Well, man, nowadays with the the rise of ultra running in 200 plus mile events, it seems like in the early two thousands, you would think about, like, delaying people from doing a marathon. Now it’s like ultra runners wanna jump into a 100 miler without doing, like, a 100 k first.

00:34:04.420 –> 00:34:05.220

<v JF>I know.

00:34:05.380 –> 00:34:08.180

<v Jimmy>It’s very hard. Yeah. Do you see that where you are as well?

00:34:08.340 –> 00:34:27.355

<v JF>Yeah. I I do. The nice part with longer distances on the trails is you can be, a hiker. You can hike a lot of it and and still make it to the finish line. Like, technically, if you’re a very good hiker, you would be able to complete these within the the cutoff times.

00:34:27.610 –> 00:34:35.370

<v Jimmy>When you do the math, it’s kind of surprising the pace that you have to maintain and get even like a sub thirty hour 100 mile race. Right? Mhmm.

00:34:35.370 –> 00:34:36.170

<v JF>It’s not Exactly.

00:34:36.730 –> 00:34:38.410

<v Jimmy>It’s more hiking than you think. Yeah.

00:34:38.410 –> 00:34:43.715

<v JF>Yeah. So that allows your body to increase the volume a bit faster usually.

00:34:43.715 –> 00:35:04.640

<v Jimmy>And safely. Yeah. That makes But let’s go back to the first study with the gait retraining arm. Looking at your research, it seems like you’re a fan of gait retraining and using it as a way to, like you said earlier, unload tissue. What does your current gait analysis look like when you see a runner, whether it’s that second visit, you got them in there for your gait assessment.

00:35:04.640 –> 00:35:07.040

What are you doing during that gait analysis?

00:35:07.280 –> 00:35:44.285

<v JF>So we offer like two packages basically at our clinic. One is the more simple straightforward one, the other one is more detailed like full biomechanical assessment. So typically I’ll I’ll make sure the runner is comfortable running on the treadmill first because you it can be quite, strange running on the treadmill if you’re not used to it or or not never ever training on it. First thing first, I’ll I’ll give them, some time to warm up, make sure that their gait feels normal to them, they’re happy with the speed. I like to do it at, more endurance pace unless they tell me they only have symptoms at faster pace, but I typically do it at endurance pace, conversational pace.

00:35:44.285 –> 00:36:30.320

The main things that I’m I’m looking at first of all is without any sort of measurement, it would be how loud are they, so their impact on the treadmill, and counting their cadence so you can use apps for that. Pretty simple. And I’ll do usually a video analysis, slow mo, full body side view, side view close-up of the feet, front view, and back view. That’s kind of the basic one, that we like to do. If we go a bit deeper into this I also like to see people running barefoot and compare how they run which shoes on and running barefoot and I’ll come back to that after and then we’ve now been using the run easy system in the clinic just to give us a better idea of impact metrics of, symmetry.

00:36:30.400 –> 00:36:55.235

And that’s particularly useful in people post op, for example, that we’re seeing in the clinic. So going back to running post op, are we needing something more in terms of confidence in their leg, terms of ability to absorb load, impact jumping exercises, things like that. So it’s very useful that way. So that’s what we have in our more like complete package and we send out the recommendations and videos with voice over after and all that stuff.

00:36:55.540 –> 00:37:11.235

<v Jimmy>Nice. Cool. And then in a typical gait analysis, and maybe there is no typical, maybe it depends. Are you looking to we can go two avenues with it. We can say, let’s change the gait to unload tissue or assess your gate to understand how you’re loading your body.

00:37:11.235 –> 00:37:17.075

And then we could add interventions to support the way that you run. Where do you tend to go with it?

00:37:17.235 –> 00:37:42.095

<v JF>That one is very individual in the sense that to me, regardless of how you run, you can be fully adapted to it. Mhmm. You can have high impact, low cadence, a lot of vertical bounce, be a heavy heel striker and you’ve been running like that for twenty years and be totally fine. Right? So in that case, if you’re not injured, you’re not trying to be more efficient when you run, I’m not going to change your running gait.

00:37:42.095 –> 00:38:14.885

So I’m going to play with the rest, the outside of the running gait. But if if you’ve been injured consistently, there’s always something coming up, it’s it’s it doesn’t seem to be linked with a clear training error that’s recent, then in that case I’m trying to reduce the load on that particular tissue when you’re running. So if it’s knee pain, I’ll try to increase the cadence, run softer. Another big intervention that I like to use is changing your shoes, trying to make you feel the ground better. We know that you reduce, load the knee significantly with more minimalist shoes.

00:38:14.885 –> 00:38:33.215

So they need to be implemented gradually. But it’s an intervention that I think a lot of people fear. Yeah. And the market of running shoes, which would be the topic of a completely different podcast because we’ve talked about shoes for a while. But right now it’s all about highly cushioned shoes and it’s not I don’t think it’s the best way to go.

00:38:33.215 –> 00:38:38.815

I think we need to educate people that if you have more cushioning under your feet, you’ll have more loads

00:38:38.895 –> 00:38:39.135

<v Jimmy>Yeah.

00:38:39.135 –> 00:38:42.495

<v JF>At your knees, at your hips, at your low at the low back level.

00:38:42.495 –> 00:38:52.740

<v Jimmy>It’s counterintuitive but I guess we see that. I feel like I saw you had a study with, a maximal shoe and a racing flat and a Vaporfly or something like that.

00:38:52.820 –> 00:38:58.340

<v JF>Yeah. We did a few studies on, different types of running shoes and how they affect loads and how they affect performance.

00:38:58.535 –> 00:39:10.455

<v Jimmy>And then now you look at the shoe industry and like the stack heights have gone crazy. Maybe they’re starting to come down. But I remember looking, trying to find just like an old school racing flat and like they’re hard to find these days. No one’s making them.

00:39:10.710 –> 00:39:30.465

<v JF>It’s really hard. Yeah. I know. It’s, unfortunately, that’s how the market is right now. But like if if you’re a health care professional dealing with people who have pain in their knees and their hips and their low back, and there are like brands out there with, more minimal issues and they’re just not as common in the typical running store, but they can make a difference.

00:39:30.465 –> 00:39:55.530

Like, you reduce load at the patellofemoral joint by 15 if you drop that shoe. So going from, say, a minimalist index score that I I use quite a bit in the clinic, going from, say, a 20%, that’s the typical more cushioned maximalist shoe, to a shoe that has 70% on the scale, it’s nothing extreme. Like, it’s not a Vibram five fingers. Like, it’s Yeah. It still has a bit of cushioning.

00:39:55.785 –> 00:40:10.345

It’s still a shoe that offers some protection. But going to a 70% shoe gradually like that will help you reduce the load at your knees and help you implement that higher cadence and implement the gate changes that you’re trying to get.

00:40:10.760 –> 00:40:24.360

<v Jimmy>Yeah, we could go down this big rabbit hole. I’d love to, but I know we’re running low on time. You brought up adding Runeasi to what you guys do in the clinic and off air you mentioned a case. Do you want to briefly like go over this total hip replacement patient?

00:40:24.360 –> 00:41:15.230

<v JF>Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, it’s a new research interest of mine, I should say, the past few years is looking at returning to running after joint replacement surgery. And I had this patient recently who came, unfortunately had a traumatic hip fracture and had a hip replacement surgery as a result. The patient is about late sixties, around 70 years old, has been a runner all their life, really enjoys running, wanting to get back to running ASAP. So obviously we did the whole rehab process first and decided to wait for after three months before considering returning to running but we built up the walking first and then when, we felt like it was the right time we looked at the person running on the treadmill with the RunEZ system and just trying to see, is there any significant difference in, you know, are they trying to protect that new hip?

00:41:15.230 –> 00:41:42.910

Is there an asymmetry that that would lead us to think that, okay, maybe they’re not ready to go back to running. Maybe we need to work a bit more on impact absorption through exercises outside of running first. How is that, the stability of the pelvis when landing as well was an interesting metric in in that person. So making sure again that their muscles are ready to tolerate impact. And it turned out that in that person specifically, the differences were very, very low left versus right.

00:41:42.910 –> 00:42:09.210

So we had we had about if I remember correctly, it was about 10% difference right versus left. So we still decided to go to move forward with the running and, and still push on exercises outside of running to to help with that. And I’m following up with them actually today. So we’ll see we’ll see where we’re at. But they’re back now to running about an hour and feeling great.

00:42:09.210 –> 00:42:20.170

No issues, no no hip pain, no lower limb pain in the process. Yeah. It’s been a very good tool to also give confidence to the person, feeling like, okay, I’m ready.

00:42:20.565 –> 00:42:30.965

<v Jimmy>Need to go back. With this individual, yeah, you’re able to show them with data and say, hey, like, you’re actually pretty symmetrical. You’re not favoring this too much. We have a green light. Yeah.

00:42:30.965 –> 00:42:52.545

So you can inspire them a bit to that it’s safe to load. And I’m sure, coming off a total hip replacement, that we want all the confidence that we can give them to get them moving forward. Yeah, that’s great. You are on your way into the clinic now, so I don’t want to take up too much more of your time. This has been a great conversation for listeners who want to learn more about you in the running clinic.

00:42:52.545 –> 00:42:54.385

Where can they go? How can they find you?

00:42:54.465 –> 00:43:17.795

<v JF>I mean, running clinic, we teach courses all around the world, so you can find more information on therunningclinic.com. If you are interested in hosting any of our courses, just let us know. Send us an email infothrunningclinic dot com. Other than that, people can follow us on social media, Instagram therunningclinic. We post stuff about new research, about updates to things that clinicians wanna know.

00:43:17.875 –> 00:43:27.955

Personally, my clinic I I’m located in Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada. MoveMed Physiotherapy is our clinic. And, yeah, other than that, I think people will be able to find us, that way.

00:43:27.955 –> 00:43:38.700

<v Jimmy>Awesome. Yeah. And then go check out all JF’s research articles. There’s lots of good stuff in there. And with that, JF, yeah, I hope you have a great day, and thank you so much.

00:43:38.780 –> 00:43:46.060

<v JF>Thanks, Jimmy. Thanks for having me. It was a pleasure, and, really looking forward to our next conversation. I feel like we’ll have, more stuff to talk about.

00:43:46.385 –> 00:44:05.990

<v Jimmy>Yes, sir. That’s it for today on the Physio Insights podcast presented by Runeasi. Would you like to share an interesting case, insight, or have a thought about the podcast? Comment below, and don’t forget to follow us for more episodes.