Talking Bone Stress Injuries (BSI)

With Dr. Stephanie Mundt

In this episode, Dr. Stephanie Mundt shares her powerful journey from a young runner battling injuries and disordered eating to becoming a leading physical therapist in bone stress injuries. We explore the nuances of diagnosing and managing these injuries, the importance of energy availability, and the evolving roles of rest, coaching, and individualized rehab. Whether you’re a clinician, coach, or athlete, this conversation is filled with insight and practical takeaways.

Key Notes

Misdiagnosis and Clinical Awareness

- BSIs often misdiagnosed due to lack of education.

- Outdated “rest 6–8 weeks” advice is still common.

- Prior BSI is the strongest predictor of future BSI.

Importance of Subjective Evaluation

- Use LEAF-Q and RED-S screening tools.

- Screen for menstrual health, GI issues, training history, and eating behavior.

- Emphasis on risk profiling to guide assessment.

Nutrition and Communication

- Approach nutrition discussions with empathy and curiosity.

- Look for red flags like food morality and rigid diets.

- Highlight carbs as critical for bone health, not just protein.

Imaging and Objective Assessment

- Early MRI essential for high-risk sites (e.g., femoral neck).

- Recommend cash-pay imaging to reduce costs.

- Suggest second reads or CT for suspected false negatives.

Rehab and Return-to-Run

- Rehab progresses from non-weight-bearing to plyometrics.

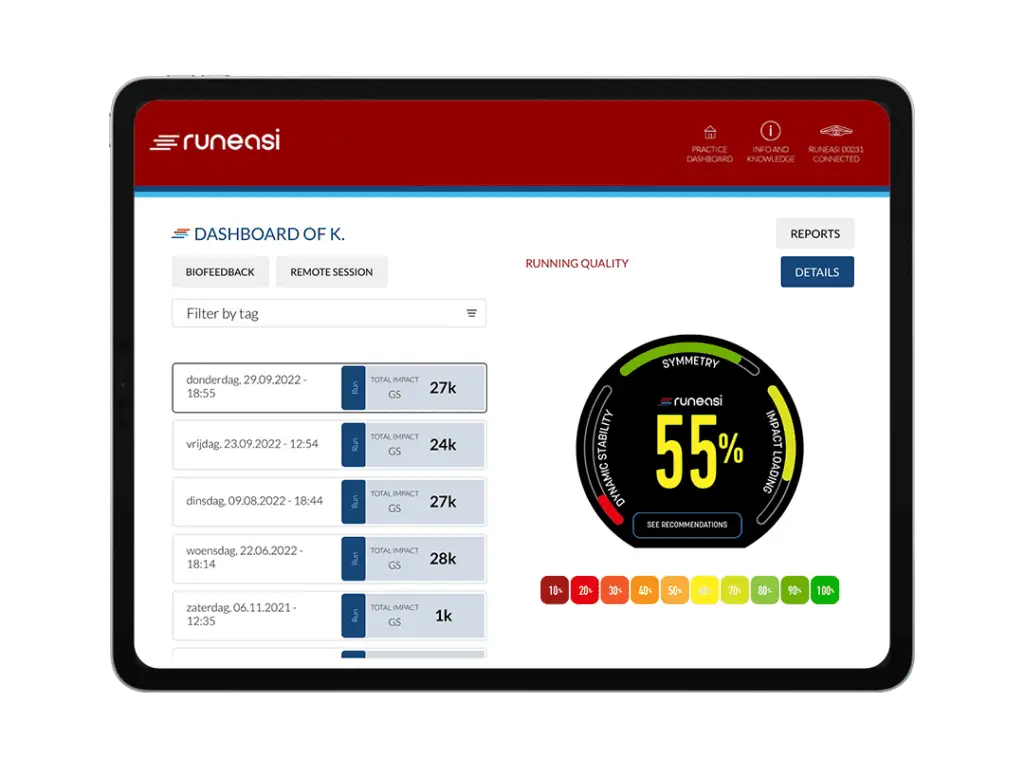

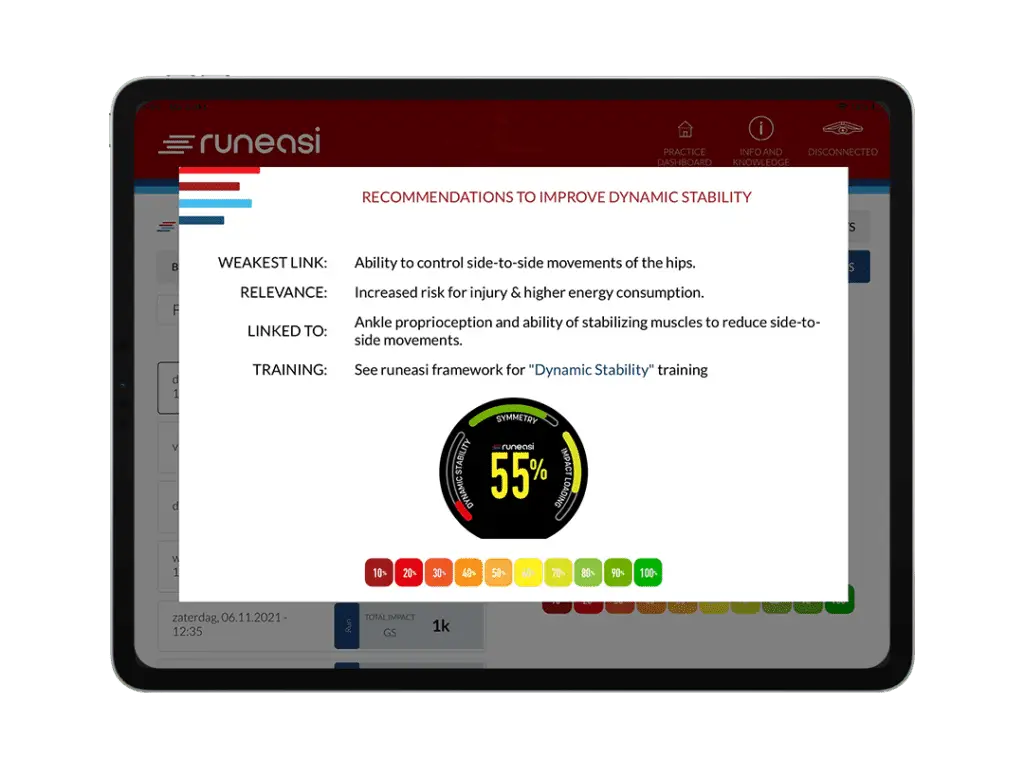

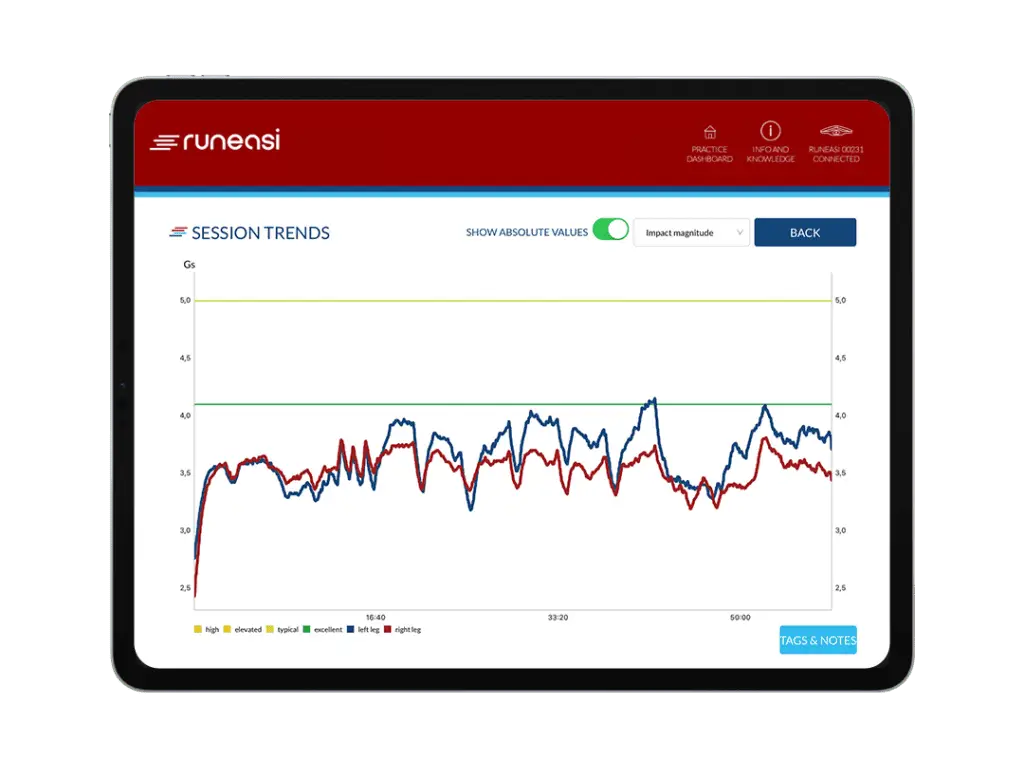

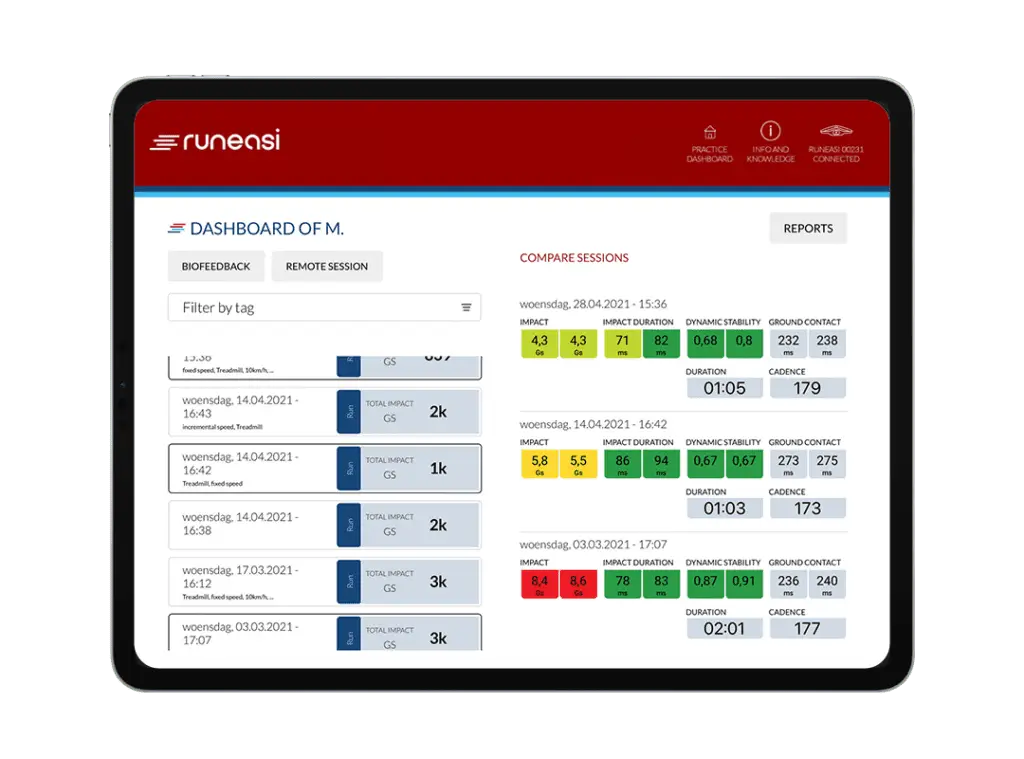

- Use tools like RunEasi to track asymmetries.

- Focus on load management and functional readiness

Coaching and Performance

- Transitions athletes from rehab to coaching.

- Teach deloading, intensity control, and training balance.

- Promote strength and periodization for safe performance gains.

Full Audio Transcript

Jimmy (0.00:07)

Welcome to the Physio Insights podcast presented by Runeasi. I’ll be your host, Dr. Jimmy Picard. I’m a physical therapist, running coach, and team member here at Runeasi. On this show, we have real conversations with leading experts, digging into how we recover from injuries, train smarter, and use data to better guide care. Whether you’re a clinician, coach, or an athlete, we’re here to explore what really matters in rehab and performance.

Let’s dive in.

Stephanie:

Thank you so much for having me. I’m excited. Awesome. To get started, why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself, kind of where you grew up, sports you played growing up and all that kind of fun stuff.

So I’m originally from Iowa. I grew up in a suburb there and ran track and cross country and kind of had the unfortunately typical experience that a lot of young runners have where I started to run fast in high school, then developed an eating disorder and had subsequent bone stress injuries. but I was still Succeeding enough that I ended up getting a scholarship to go to Arizona State University So I went there for undergrad and was on the track and cross-country teams But didn’t race very much because of my bone stress injuries and continued struggles with an eating disorder So after that I actually ended up recovering and stopped running for a couple years then I went to physical therapy school at USC and Here we are.

Jimmy:

Yeah, I feel like I’ve heard this quote recently that, something like the universe gives teachers pain so that they can learn to overcome and help others do the same. You’ve experienced it from the other side of the coin and now you’re out there helping people overcome injuries and deal with problems with bone stress injuries. And that’s kind of your niche now. Is that right? Absolutely. Yeah. So my experience wasn’t, I guess.

Stephanie (0.02:01)

Optimal, I’d say looking back at the time, you know, the guidance, which I think was all we knew there wasn’t a ton of research on this, but the guidance was take six to eight weeks off and then try running again. And I’m sure you’ve had athletes who have gotten that advice still to this day. So, honestly, I remember when I first graduated, that’s just what I was taught to do. Yeah. Right. Yeah. Yeah. So

Then coming out of that and rediscovering my love for running as a recovered individual, I kept getting bone stress injuries. And so I thought that there had to be a better way to manage these. And I’m so grateful to the researchers and the universities who are looking into this a little bit more, but still trying to help educate other clinicians on diagnosing bone stress injuries. I think there’s still a lot of misdiagnosis going on just because we didn’t.

Learn about how to do that. And as physical therapists now where we have direct access, but still without some of that education piece of what to look for to diagnose these, especially higher risk BSIs. and then just helping to improve the management of these injuries, not just through that initial phase of return to run, but then when it gets a little bit harder, I think when you’re returning to training and higher speed running and performance and how to really change the narrative of what training has to look like.

Jimmy:

For individuals at a higher risk for bone stress injury. Yeah, you said a lot there. There’s a lot to unpack. So yeah, my mind went towards helping. Can you help me understand like what a subjective exam looks like for you when you’re dealing with a patient or a client that you suspect has a bone stress injury? Are there certain things, I guess, to start with that you’re adding into your intake form maybe? Stephanie (0.04:15)

Yeah, that is definitely the very first part that I think guides are for our other questions. In my intake form, I do have pieces of the left queue questionnaire, low energy availability in females questionnaire. There is one for males as well now. I’m not sure if it’s validated yet, but some of the questions go into for females, their menstrual cycle for both males and females, GI symptoms and injury history. And so some of that can kind of give you a feel for what their risk might be. So if they have a history of eating disorder, or disordered eating, dieting, restrictive eating, anything that might contribute to lower bone density or that female athlete triad is kind of the, it still exists, but has kind of morphed into relative energy deficiency in sports.

And so that’s on the intake questionnaire. Also just recent changes in training. That’s kind of one that really increases my radar or relates up my radar for bone stress injury. If they’ve had recent increases in volume or especially intensity in the past weeks to months, not necessarily a day before a week before these are injuries that tend to be delayed and come on after several weeks of increased load. No, but if it’s someone who hasn’t run in a while and they’re having pain with.

Single eye cough and pain at night, then it’s less likely to be a bone stress injury, of course. So looking at their training history and looking at the answers to that questionnaire on their menstrual health, GI symptoms and injury history, and then asking just about their own, with that injury history, their own bone stress injury experience so far, because the number one risk factor for a BSI is a history of one. So that kind of raises the alarm bells a little bit more if they’ve had one. Yep.

So then once you’re sitting down with the patient and yeah, you’re suspecting bone stress injury. I think for me, it’s like there’s, always trying to dig into training history. So I’m sitting down asking them to kind of go through their training history and, like, yeah, how valuable do you think that is to kind of like pull up their training history and go through it? I think it’s super valuable.

Because I think a lot of times athletes don’t feel like they’ve increased their volume or their intensity much, but if you’re able to even put like a percent increase to it, had an athlete in the other day who, increases vert from 5,000 feet one week to 8,000 the two weeks after. And he didn’t feel like he had increased much, but when you do that percentage, that’s.

Stephanie (0.06:14)

what over a 50% increase two weeks in a row. So I do think it’s really valuable to do that. And you may not have to do the math, but just to kind of point out that this may not be something that just kind of came out of nowhere and also help you understand if this pain started, you know, five to 10 weeks after a change in training, that’s typically where we see bone stress injuries come on. So that also might contribute to your suspicion. Yeah.

And I guess like along the same line, sometimes the runner doesn’t even realize that they’ve made this big change, right? Right. Or they think it’s reasonable and they need you to be like, yeah, this was probably not very logical to make these big jumps that you did. I had a guy in here that we were talking about earlier before the recording started, but the fibula stress fracture guy, he had gone from running zero amount like none to

His first week he did a five mile run, second week seven, then 10, then 13. And then he just stayed at 13 miles once a week for I think two months. So I was like, oh, that wasn’t very logical there. And we had to point that out.

Strava can be really helpful for that too, of seeing the graph, you know, that’s similarly, I think we forget about cutback or deload weeks, which can be really helpful for bone, but you’ll see on that Strava graph just up and up and up. always tell people the word, like when I pull up Strava, the thing I hate the most is just that like plateau where they got to like their peak mileage and just stayed there. red flag. Yeah. So first, yeah, digging into the, maybe some potential training errors, then

Jimmy: (0.08:16)

At what pint or how are you approaching questions about nutrition, diet, things like that? Because this becomes a little bit sensitive. again, like last week, I had somebody as soon as we started opening this can up, like she started crying and it’s like becomes a very emotional thing. I think sometimes we as clinicians can be a little like, we don’t know how to unpack all this. And yeah, so what advice do you have for that? Yeah, yeah, this is such a great topic to get into. So

Stephanie:

In addition to the questions about fueling or history of eating disorder on my intake forms, I also just have a question that says, what is your relationship with food like? And that can also give a little bit of insight sometimes because a lot of athletes say it’s good. get enough protein. I let myself have snacks or treats on the weekend. And so that also kind of raises some, questions in my mind. I think initially

This was really challenging. Sometimes I would just skate over it in my early years because it is uncomfortable even as someone with a history like this. But now I think really coming at it from a place of curiosity and addressing the, what they, what they mentioned, you know, it’s easier for people to write things down sometimes than say it. So, Hey, you mentioned this in your intake forms. Can you tell me a little bit more about it? And even before that, I think I try to make sure all of my patients and athletes know that.

If I’m pushing too far, if there’s anything they don’t want to talk about or aren’t ready for, that’s okay. Just tell me to stop. I’m not offended. Just tell me that’s too much. We’re not going there today. That’s also totally okay. But tell me a little bit more about what you mean when you say let yourself have.

Treats on the weekend. And do you have any thoughts about what having an additional treat during the week, what would that do? Is that a bad thing to you? And just kind of getting a little bit more of a sense of that relationship because it doesn’t have to be disordered eating for someone to be in a low energy available state there. I think a lot of times athletes just have these rules and these habits that have been normalized. And sometimes you do have to have that, you know, I think there’s, there are maladaptive and adaptive nutritional tendencies. I’m not the one to judge.

That which it is, but that can also help guide the conversation too. I’m asking these things because it’s been shown that fueling has a strong relationship with your risk for bone stress injuries. So really I’m just trying to get a picture of what may have contributed. We don’t need to nitpick these, but what may have contributed or if this is a factor for you. And if you’re open to it, seeing a registered dietitian for some more assistance with fueling here, especially if it’s a trabecular rich site that’s more associated with.

Stephanie: (0.10:24)

restrictive eating. So curiosity, think to summarize all that coming from a place of curiosity and making sure they know that they the ball is in their court. There’s nothing that they have to share that they’re uncomfortable with. Jimmy:

That’s awesome. Yeah. So coming approaching it kind of gently being curious, giving them the pass to like, they don’t have to talk about it if they don’t want to. And you’re trying to help them understand at the same time, why it is that you’re asking the questions and why it’s important to help kind of for you to make your diagnosis one way or the other.

Absolutely. Yeah. And I think for, I know for myself as an adolescent with an eating disorder, future, like fear mongering about my future health didn’t really make a difference. But when it was brought up that fueling better might improve my performance, that’s where it started to click. And not that that’s the healthiest way to go about it. You know, I think also explaining that these things can be helpful for performance and whatever bad things you think might happen from having an extra snack or not, or you know, having that extra donut is probably not going to happen. And your performance and your longevity can also improve by addressing this aspect.

Jimmy:

Yeah. All right. When they say things like the snack thing, that this is almost like a yellow flag or like your Spidey sense goes off to like pay more attention, right? Are there other things like that, that you’re kind of like perked up, that make you perk up or that you’re looking for them to say to kind of, kind of guide you towards this is a bone stress or this is a low energy availability situation?

Stephanie:

Yeah. Comments about kind of food or certain food groups having a morality piece, like these are bad for you and I try to avoid bad foods or something about race weight and I race best at this one, which again, some of these things can be true, right? just, it’s, it’s coming from that’s not wrong, but I want to understand more of what led you to this belief and see if that is something that’s impacting your injury risk.

In the past few years, feel like in the fitness world, there’s been this bigger push for protein intake and high protein intake. And there was that IOC statement that talked about carbohydrate availability being a big predictor of bone health. Can you talk on that a little bit? Is that something you’ve heard? Yeah, that’s true. And there’s been some…

Stephanie: (0.12:38)

trail athletes, probably some road athletes too, but trail runners who have been promoting a keto diet, which again, maybe that works for some people. But if you have a risk or a high risk of bone stress injury or a history of bone stress injury, your bones seem to respond really well to carbs. So it’s not just energy availability that’s going to impact the ability to form new bone and remodel, but also carb availability. And I think one of the main studies that I know I’ve referenced was on male race walkers. So we probably need, we definitely need more research.

Females as well. But they found that those who had low carb availability and actually had enough energy had decreased bone formation markers and increased bone breakdown markers. So that’s definitely a huge piece. And protein is important, but it’s not the star of the show for endurance athletes. Yeah, I guess I almost feel like I’ve seen people so focused on the protein goals that they’re skimping on carbs and that it’s putting them in that state. And I’ve also seen, yeah.

For me, a red flag is the clean eater who my diet is really good. you’re like, all right, tell me more about this. I had a guy recently who like, he had a full on fifth metatarsal fracture, not stress fracture, fracture from running. he was describing his diet as super clean, it’s perfect. But he was in the extremely low carb camp.

And yeah, it’s like once it’s really that becomes a very tricky situation that I’m not going to navigate. just kind of gloss over and I guess refer him to a dietitian or a dietitian for you personally. Like when are you making that call or you just kind of as soon as you think it’s a problem, you’re just going to automatically recommend that they refer them out.

I definitely will push it a little bit more in athletes with a trabecular site of injury, since that is more highly associated with disordered eating or restrictive eating. For those with cortical rich sites, so more like the shafts of the bones, I will still suggest it. I think most athletes are probably under fueling to be honest. So I’ll put it out there. Here’s that information if you want it. Again, there’s sometimes the angle of performance that can help push them that direction. And then they might discover through that referral that they have some other things to work

Stephanie: (0.14:56)

on with their relationship with food or they may not and they’ve just unintentionally been under fueling. It’s definitely a little bit more of a push for those trabecular sites where I think that it might be more of an issue and then just take it or leave it for other athletes. But it’s pretty much a recommendation that’s out to everyone with a bone stress injury. So in your experience, where do you feel like low energy availability fits in with bone stress injuries? Is this like always the case that if you have a bone stress injury, there was low energy availability or yeah, like what is your experience there?

Stephanie:

Yeah, not necessarily. And that’s what makes it so hard to because, you know, you can be doing everything right. Quote, right. That’s, you know, that definition is going to vary from one person to the next and one training cycle to the next.

But you could be in an energy surplus and still get a bone stress injury, unfortunately. But where I think it’s just more of a significant contributor is to these sites like the femoral neck, sacrum, pelvis. We know that they’ve got higher turnover and respond of more of like a hormonal response. Calcaneus is another one. those are definitely.

going to be like, all right, we need to make sure we address this piece too. In other athletes, I’m going to, or other sites, I’m going to mention it, but it’s lower on the list of things to address unless of course they tell you straight out that they have been restricting their eating or have a eating disorder. But to summarize that it’s definitely possible to have an energy surplus and still get a bone stress injury. And in those cases, I think we just look a little bit more at training errors, maybe even biomechanics. Yeah. All right. Great.

Jimmy (0.16:57)

So to wrap up the subjective exam, there anything else like your or any recommendations you have, things you think that, yeah, where do you feel like clinicians are going wrong with this objective exam? Or is there something that you would want to make sure like every clinician, if you could, if you have the power, you can make every clinician like make sure that you don’t forget to do this during their subjective exam. What would it be? Yes, I think this is going to combine subjective and objective, but

Stephanie (0.16:57)

Anytime an endurance athlete, especially a distance runner comes in, having bone as the possibility on your radar, making sure that that is considered at the very least and proving to yourself that that’s not it. know, I think SI joint dysfunction is a, you know, kind of umbrella, you know, term that doesn’t mean much. And I’ve seen that be the diagnosis for what was actually a sacral bone stress injury, hip flexor strain diagnosis for what’s actually a femoral neck bone stress injury. So. Kind of just coming back to what we did early on in school, differential diagnosis and what would make sense for an athlete doing these things, you know, similar to bond strain instead of a femoral shaft BSI. So just making sure that you have it on your list and you’re doing tests to determine whether or not bone is involved. And then if there’s any possibility or it’s high, medium to high on the list.

Referring out to get that image because worst case, I know it can be challenging to get imaging, but worst case you got a clean image and then it’s, you know, full go. So no breaks, just continue with training and modify based on the level of pain because the treatment approaches are so wildly different, bone versus not bone. So along those lines, when you’re, when you are suspecting it and you’re going to refer them or recommend an MRI or an image, I’m assuming it’s always going to be an MRI. You’re always going to push them to MRI.

Jimmy:

Which are expensive. How do you as a clinician like tackle that? Cause it’s like, I kind of feel a lot of times I run into a little hangup. I’m like, man, I feel bad. You’re spending money to come see me. And now I’m telling you, man, you gotta spend more money. like, yeah, does that’s a problem you have? Do you notice, is that something you feel and how do you deal with it?

Stephanie:

Absolutely. Yeah. There is this kind of feeling of if I’m wrong and they wasted their time. So we have to separate yourself from that because the, you have a high suspicion for it and you’ve gone through the clinical reasoning, you know, we can’t just assume that anyone with unilateral low back pain coming in as a sacral bone stress injury, but you go through kind of the questions we talked about, create your own little cumulative risk profile and the odds are high then.

Jimmy (0.19:11)

You can’t, you know, I think in my mind, I think I can’t in good conscience, let this person just continue running. And again, you know, most of the time actually never has someone said, Oh, that was such a waste of time. It was negative. I’m so mad at you. It’s more of, Oh, what a relief. Now we know the plan and we can have some certainty in moving forward. And here actually we can order imaging now in Arizona, which is really nice. There used to be kind of a barrier.

okay, I’m going to send them to the sports med doc and there’s just more time in between there. Often they can use insurance for that even if you’re not an insurance-based clinician or a little life hack. In some states, the cash rate is actually a lot cheaper than going through insurance. So I recommend to everyone calling the imaging center and asking what the cash rate is for that location that you need an image for and seeing if that’s actually more affordable. Yeah, so two things there.

I worked in Salt Lake for five years or seven years. We just recently moved to Virginia and Salt Lake had a couple cash based MRI clinics where it was three ninety nine and you could get any body part MRI like within like within a couple of days. You just send them there. No script needed in their referral. It was. Yes. I’m like, well, they need to have these things everywhere. But then to pick up on your cash pay price, my wife.

a years ago, she had a femoral neck stress fracture and we did the thing calling around trying to get what’s the cash pay rate and we got it for like a third the price of what it would have costed to use insurance. So it’s definitely a little trick. Yeah. Yeah. So that’s great. I guess one thing to piggyback off of that last question is are there ever cases where you and the patient kind of agree that you’re not going to get imaging and you’re just going to treat this as if it were positive?

Stephanie:

Yeah, and that’s a tough conversation to have too. You know, especially early on, if you have high suspicion, then and it might take a while if they do have to go to the ortho and then scheduling out with their insurance, some people need off, you know, it might take a month to six weeks. And so I do talk to them about that. These are this is where I would go, you know, air on the conservative side. And we’re to treat this like a bone stress injury until we get imaging and point.

Jimmy (0.21:30)

may not show up at that point either. There have been cases too where someone’s just not able to get imaging. So we do treat it that way. And there is a risk of underloading someone. And so that’s the downside to that because if you’re able to get an image quickly and then you can return and they’re off less time because it was soft tissue or may just be nothing on the image. And that’s always a positive sign too. So I have had cases where we do that and it’s not ideal, but you just have to kind of work with what they’re able to do.

Yeah. So then one more question on imaging and we’re moving on. What are your thoughts on like imaging comes back clean, but your suspicion is so high and you’re like, I want to like, can I get a second read something like this? Does that happen to you? And what do you do in that situation? It has. the usually I actually personally had a false negative on an MRI once and so how we treated it is kind of how I didn’t follow. So.

It was a fibular stress reaction. So first look, the image was clear. And so I kept trying to run, but I kept having pain. And then my coach is also a PT, so I think you need to get a second opinion. the image to a new doc and he pointed straight to it. So I think at a high risk site, if they’re still having pain with walking and all the clinical symptoms still point to that, still be conservative, still treat it that way.

maybe gradually ramp them up a little bit more quickly than if you knew for sure it was a bone stress injury. But if pain comes back, that’s when that second opinion or another MRI would be helpful. think second opinion first would be good on that same image. And this is where I think it’s just so important to have clinicians in other fields around you and have sports med docs that you can refer out to who can read that imaging better than we can. And get…

I think that’s like an opinion that could be really helpful either in the way of no, you’re fine. This looks good. Or actually, I think I see something here. You need to change the and to sounds like to like trust your instincts or your gut. it doesn’t feel right. I think you had mentioned off air that Chris Johnson’s a mentor. He’s a mentor of mine as well. I feel like he’s got his hands in everything. But I was I had a suspected for moral neck stress fracture patient recently. And when talking to him about the imaging, because it came back.

Jimmy (0.23:47)

clean and he mentioned, I think he said in the past year he’s had like three false reads. So it’s definitely happening. And so I think like, trust your gut. And if you feel like you need to get that second opinion, sounds like is the consensus here. Yeah. And for the navicular, if you still have high suspicion and there’s a false or there’s a negative on an MRI, then CT is recommended. So I wonder if there’s some other, you know, high risk sites that we should also be doing that for CT or bone scan when suspicion is high.

Stephanie:

Yeah. All right. Let’s move on to the objective exam, specific tests. I know this is a weird one because a lot of times if you’re really suspicious, you’re probably not going to do any of this stuff. But let’s say like you’re on the fence, you’re not sure. Like are there things you’re definitely going to make sure you do to help you rule this in or out? And I’m being very general. Obviously we’re talking about like every stress fracture, lower extremity stress fracture. Right. Well, I think one of them for sure, like coming back to the possible misdiagnoses of a muscular strain.

Do some contractile testing, know, test that muscle. And if it’s not painful when you’re stretching it, if it’s not painful to contract, then it’s probably not a quad strain, right? A lot of times some of these present as especially more proximal injuries. They’re kind of vague or deep discomfort and they don’t necessarily have this specific mechanism of injury. Sometimes they do come on pretty quickly, but it’s not like I definitely felt myself pull something when I was sprinting. So I think test the muscles and that can kind of move your diagnosis up or down.

the weight bearing tests. So making sure that you progress those slowly. Single leg stance first. If that reproduces pain, you probably don’t need to do a single leg squat. If that reproduces pain, you probably shouldn’t do a single leg hop. So those, you know, if there’s, you’re kind of on the fence and maybe you’ve caught it early in the stress reaction phase, then in single leg squat is pain free. Then maybe try single leg hop. And that could give you a little bit more info, but I think to rule down muscle, do some contractile testing and then testing some of their weight bearing tolerance.

And not only will that help with diagnosis, but also give you some entry points for the rehab. So if someone is, if you’re suspicious of a femoral neck BSI, that they can do a double leg bridge without discomfort, then maybe that’s what you give them initially, some kind of like partial weight bearing. Or if you’re going to do some non-weight bearing stuff and non-weight bearing hip abduction is painful, then we know that that’s still going to go get the image, but we’re not going to prescribe them non-weight bearing hip abduction until that’s pain free. Yeah.

Jimmy (0.26:12)

So since you’re familiar with Chris Johnson and I’m guessing Nathan Carlson as well. Yeah. He’s taught me a lot. Okay. I took his bone stress at one of his early bone stress injury courses and he talked about this like unloading test for the, from oral neck. Do you, are you familiar with this one? Yeah. Yeah. He, it’s, it’s funny cause I feel like I had had those symptoms before, but no one had ever identified it. So I thought it was cool that he brought that to clinicians attention.

And I think I’ve seen it positive in femoral shaft bone stress injuries as well. But I’ve also seen that positive in labial tears where, you know, liberal tear versus femoral nephia, I can present so similarly. And so I think it’s a really important test to have as part of your, again, like these cumulative things like, OK, that was positive. It may may make it more likely. It may not be 100 percent specific, but it can be helpful. Right. So it’s a it’s a piece to the puzzle. Yeah. OK. you seen that in clinic, too?

What’s that? Yeah, definitely. And it’s like something I like test with everyone where I’m suspecting it because it’s I can do that. Whereas I probably hop with every single patient. Right. It’s a very it’s a safer test. But I have seen like right now I have one guy where this is like this is positive and I am I’ve been it’s like everything else is pretty good. And so to your point, maybe this is just a label tear. But it’s like I don’t like that that that is something that’s bothering and bothering him.

and you kind of have to get the image to know. And then it just really guides your treatment path. Is a little pain okay or is it not? Yep. Yep. But yeah. So for me with this case, like suspicion was low enough where we have started like a return to run program and it’s not provoking symptoms. I’m like, phew, clear. Yeah. During the subjective exam, I’m like, man, I don’t like that. Yeah. There’s like that little pit in your stomach. How do I present this? I think I,

you you practice more, you get a little bit more accustomed to presenting tough information, but often at the beginning of our evaluation, if there’s any suspicion of it, then I’ll just put it out there. You know, hey, one of the main things we want to make sure that we’re not missing is a bone stress injury. Here’s Y, X, Y, Z. And so then if it wasn’t on their radar, now it might be, but without leading them into a panic of, you know, we just want to rule this out so we know what direction to go.

Jimmy (0.28:36)

Yeah. So for continuing in this objective exam, like where do you feel like gait analysis plays a role or biomechanics play a role in the, the one assessment to like the development of a bone stress injury? Yeah, gosh. Um, in the evaluation of someone who you might suspect about stress injury, you know, not going to go there, their gait’s probably going to be changed if they’re in pain and we might risk making it worse, especially if it’s a high grade or a high risk site. So.

I think the talking about gait has more of a role later in rehab with the return to run process and more so in the cortical rich sites. You know, I think if you are trying to change someone’s gait or thinking that’s a big contributor to a femoral neck or sacral DSI, probably missing the mark. Those foundational pieces are likely going to have more of an impact than their gait. Even though that could be contributing a little, it’s kind of top of the pyramid. Whereas cortical rich sites, especially athletes with repeated

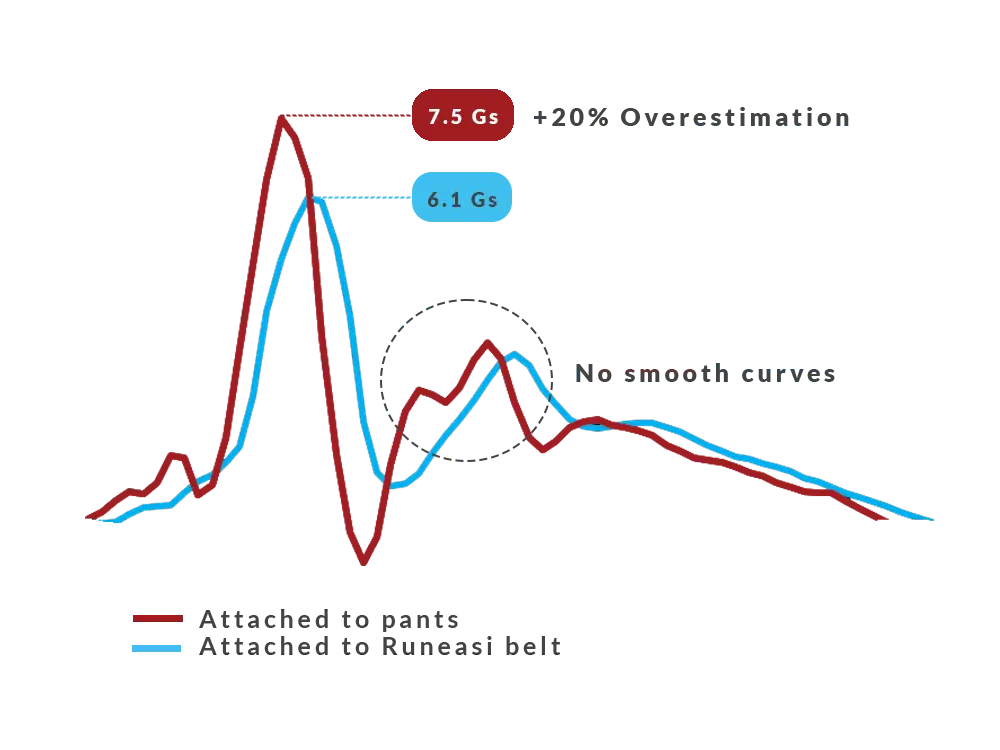

sites like fibula, metatarsals, posterior medial tibia, that might be something that you look at a little bit more as they’re getting back into running and kind of finding their normal gait. And then you can utilize it as a tool to help offload that injured site getting back into running. know, Rich Willie has talked about this and has taught me a lot about this as well of looking at their gait pattern and seeing stuff or noticing stuff with Runeasi too that you can’t necessarily visualize, but it’s showing you, they’re not actually loading that side very well. So

Now, maybe we test calf strength or hip abductor strength and find some other things we need to work on that then may contribute to a, quote, improved or more symmetrical gait pattern or changing their stride, increasing cadence to reduce some load on maybe the femoral shaft or the fibula because of just the way the load is distributed from a compressive, intensile perspective. Cool. So during the eval, less important.

It’s probably not on your radar because you’re you just don’t they’re going to be running differently because they’re in pain. Then you go through your treatment. They’re initiating a return to run. This is when that’s the time frame for you when it becomes important. You’re going to like throw them on the treadmill. You’re going to look at. So we flash forward to that point. We’re out of the object or the eval. We’re starting to return to run. Like what are the specific things you’re looking for? You just looking for symmetry or like what are you looking for when you see them run?

Jimmy (0.30:55)

Yeah, so depending on the site, I guess that’s also important. the really for the cortical ridge sites, I want to look at if they’re having a crossover from the Runeasi data, we also get dynamic instability, impact loading and impact duration. And so I’m looking at from a dynamic stability perspective, are they having a little bit more wobble on one side? I know that’s typically noted as more of a measure of efficiency, but that will also lead me to test their frontal plane hip strength.

And so then it’s, okay, how can we change their strength program to match some of the things we’ve seen here? Also just looking at symmetry for their impact magnitude, because sometimes they’re not landing as hard on that injured side. And we don’t know, but maybe that is one way that’s actually contributing to some tissue changes on the other side, right? If we were to load them up and have them start training really hard in that pattern, could that increase the risk of injury on the unaffected limb?

Maybe, know, hard to say. So looking for some more symmetry there and then impact duration, giving us a look at the shock absorption. I think that one is a little bit more in my head of, okay, you know, this is not something I’m going to directly change, but this might change as we strengthen that side. So I guess within probably five or 10%, I know there’s some recommendations, but as close as possible, especially with these athletes, we don’t have a baseline.

Usually so they might have had, you know, asymmetries, they probably did before and what’s enough to matter. I’m not sure, but kind of getting a picture with all of the information, but just looking at their ability to load that affected side. then with their gate pattern, like I mentioned earlier with the ephemeral shaft or with the fibula, I can put a little bit more load on each of those sites. If they’ve got a crossover pattern, this is from Rich Willie. I didn’t come up with this. Thanks to him. And so.

increasing their cadence or widening their, step with a little bit might decrease some of that compressive load or calcaneally version that might be more straight on the fibula. So just using it as a tool to offset some of the loads as we return to running at certain sites, you know, increasing cadence can help with a lot of things. So that’s, that’s a nice little blanket. And then also looking to improve symmetry or tell the athlete, you know, look at, there’s some big differences still running isn’t inherently dangerous for you right now.

Jimmy (0.33:15)

But I know you want to fast and we’re not ready to run fast yet. Awesome. yeah, so you’re, so it sounds like you’re using a combination of tech like Runeasi plus your visual assessment to get the visual data of how is the person running? Are they, are they loading certain structures excessively or are they with like the visual data you’re getting for how they’re running? Then you’re using Runeasi to look at, what is, what can’t I see the forces? What’s happening there with symmetry?

between impact load, impact duration, and dynamic stability. Basically, you’re taking all these puzzle pieces and trying to put them together to make sense of what you’re seeing in front of you. Yes, you said it so eloquently. In combination with all the puzzle pieces that we were talking about, you are then taking all of that data from the visual analysis to the Runeasi data, probably even more than that, but then you are taking that information and that is what’s helping.

guide your exercise intervention or your turn to run? Like what is it? What are you doing with all that information? Yeah, exactly. So early on, I’ll try to get athletes doing as much as possible without irritating the affected site. And I think that’s one way to keep them on track and motivated is focusing on, you know, maybe some other aspects of their strength, like upper body strength or doing non weight bearing strength. That’s not painful, partial weight bearing. So they can see these incremental improvements.

with less pain or just in there, we’re not going to take fitness, but can we take fitness in a way that’s a little bit more do our best to stimulate fitness in a way that’s not irritating. so early on we’re focusing on the muscle groups that are most demanded or there’s the most demand on them during distance running. So cash complex, lateral hip, quads, hamstrings, some tip flexor. And so as we go, we’ll be testing some of those muscle groups to make sure that strength is coming along, address any asymmetries there.

I don’t think, you know, Rich really posted about this, that the single leg heel raise test, you know, that one doesn’t necessarily need to be 25. You don’t necessarily need to be able to do 20 single leg squats in order to run. But those can be ways that, again, people can gauge their progress. So even if it’s not a prerequisite for running, if they’re able to see, now I can do 10 squats on this side, either without pain or that’s improved from last week where I could only do five.

Jimmy (0.35:35)

then these are ways that I think we can help them stay motivated. then leading up to that return to run process, it’s a little bit timeline based as well as symptom based. So I’ll try to give a few weeks in each phase, kind of progressing from say we need to go non-weight bearing, then it got partial and then double leg strength, loaded double leg strength combined with some single leg body weight strength, progress to loaded single leg, double leg plyos and single leg plyos.

And the single A-COP test 10 times can be a really good test to see if they’re ready for the demands of running or by tolerating a few weeks of task blocking. Yeah, I love that. with the, so when you do your, your data assessment and you’re using like tech like Runeasi and you’re seeing the data on like stability and things like this, are you using that information to then tailor any specific exercise for the move? Yeah.

So for the example of an athlete with big differences in their dynamic stability, then I’ll actually do some other tests from that. So it’s kind of like, okay, we can use this to then test your lateral hip strength. And sometimes, you know, dynamic stability is different on the Runeasi, but then you test their side plank or you do dynamometry for hip abduction and they’re actually stronger on that side. So then it’s like, okay, maybe this is more of a motor control issue or we don’t need to address this.

So I got to use what we see and the data pulled from Runeasi to then test muscle groups and then pull exercises from that. Awesome. So everything you just described was kind of like, it was very structured and detailed. How are you, are you using any sort of like app or tech to help you like plan out patient in front of you to keep them accountable and show them? Yeah.

Absolutely. Yes. So I have two options. One is more single sessions and one is kind of a monthly programming option for rehab. And so for single sessions, I use Google Sheets. And for the monthly programming, it’s just a little more high touch. I use TrueCoach for the strength portion and then TrainingPeaks for the running. TrainingPeaks now has strength in there. And so I might switch over to just using that one, but it’s a way that then apps can make comments on anything that was a little irritating or.

Jimmy (0.37:47)

any comments on not sure if they’re doing something right or something’s getting easier and then we can adjust for the next week because I think that’s a challenging part of the SI rehab as well is some of the kind of recurring weird symptoms that people have. don’t know if you see this as well but it can be really scary when it’s like I felt something there I don’t know if it’s if I heard it again or if this is normal and so just to reassurance through that process can be really helpful.

Stephanie:

Yeah, think you bring up tooth. I want to ask about that because I think that’s like you read like papers like Stuart Warden’s paper and the zero pain is like stress throughout rehab. But then in the past, I guess I used to hear people talk about phantom pain and returning from bone stress injuries and you kind of feel that sight. I don’t really hear people talk about that anymore. But yeah, how do you how do you deal with that when they are feeling something in that area and they’re maybe becoming a little bit hyper vigilant?

Jimmy:

Yeah, I read about this in an early book and I experienced it myself. And the best way I think I can or try to explain it is there’s probably some sensations of nociception from continuing to reload or put increased pressure on the bone sites that are remodeling or healing. So I kind of create these guidelines if it’s intermittent, so you’re not having that continued ache that you had at the beginning. If it’s not reproducible,

consistently. So try your single leg slots, try single leg balance. Oftentimes you won’t feel it there. It’s more of like random changes throughout the day. And if it’s not causing increased discomfort the next day, because I think a lot of, a lot of bone stress injuries can happen. You can have pain at night and then into the next morning. And so if we’re seeing a progression that way, then that’s too much. If none of that is happening, then all is in the clear. We’ll continue as planned.

Stephanie:

Awesome. Yeah. And I think I also use training peaks to push my, do this. So I think for me, it’s been a game changer. It is not HIPAA compliant. So you have to tell the patient upfront, this is not HIPAA compliant, but it, especially with like a bone stress injury patient where you’re not like the touch points in the clinic don’t need to be high. You don’t need to have them come back all the time. And it gives you a tool to get frequent check-ins.

Jimmy (0.40:01)

They can communicate as much as they want. They’re putting, yeah, you can encourage that communication after everything. And so, yeah, they tell you something like this is happening. You’re notified immediately and you can respond to it and help like kind of calm them down, either way. So, yeah, I think there’s a lot of fun options out there for us as clinicians to help deliver a better package or a better plan of care than we used to be able to do where it’s like.

You’re either having them come in all the time and spend a ton of money, or you’re just missing them. You’re like, all right, come back in four weeks when you can walk without pain or whatever it is.

Stephanie:

Right, absolutely. And I think it’s important to highlight your point too, that manual therapy isn’t really necessary for these. I think there’s probably some schools of thought that this is too tight or this is pulling here and that contributed to you pronating too much and that led you to this bone stress injury.

There’s not evidence to support that. And so, like you said, those kind of more autonomous programs, but with frequent check-ins can be really helpful and all that’s necessary for these injuries. Yeah. So do you, with your practice, so like we’re changing gears a little bit, but like you’re dealing with a bone stress injury patient, you’re rehabbing them, you’re using the platforms to help do that. You’re starting a return to run program with them. How far along the process do you go with them before you kind of set them free?

Yeah, so we create kind of definition of done to start. And so it’s often, all right, so you want to get back to your typical level of training, or if you have a coach, you feel comfortable going back to your coach after you’re up to 30 minutes of running. So it’s very individualized. But for actually a lot of athletes, it turns into performance coaching. So I do that as well. So sometimes athletes have to defer a race. And so they want to work together through that next race to make sure they

they do it safely and have accountability as they go. Or we continue on with coaching for several races so that they feel comfortable training in a way that’s more sustainable. Yeah. So that’s awesome. I love that. So you’re, are like fully embracing this like injury to performance continuum and keeping them.

Jimmy (0.42:09)

kind of with you to make sure like, I love that you say you kind of establish what Dunn’s going to look like so that you know when you get there. Cause I think I feel like this, another Chris Johnson quote, he said something like, you’re only as good as the extent to which you’ve rehabbed your last injury or something like that. Yeah. And so you are, you’re kind of starting up for, I’d say like, all right, what does Dunn look like? And we’re going to get you there. So we’re there. You’re not going to fall off of the radar and just like, cause I, you see that happen unfortunately often.

Yeah, I love that. So then when you offer you had mentioned you, think twice now you have said something about like training, what can look different than maybe it did in the past, something like that. Yeah. Yeah. So when you’re, yeah, when you’re working on more of the performance side of things, is that, are you trying to like, I guess, unpack their previous maybe training errors, things like that and change the way they’re thinking about what training should look like? Yeah. And I think that

It becomes a lot easier when you work with someone in a coaching capacity because then they start to kind of see the results for themselves. But even without that piece, helping them understand without getting too obsessed about it, you know, I spent a lot of time going through my training logs after I got injured. like, was this the day that I overdid it? And we would drive ourselves nuts and still probably not be able to figure out the exact pieces that led to the specific injury at that specific time. But I think understanding the global principles of the first step.

Higher intensity is going to create more bone strain than easier miles and higher volume. So that’s, think, such a big piece. Our mechanics change a little bit when we run faster. Bone strain increases exponentially rather than linearly as it does with increases in volume. And so this is just the, know, we tell runners all the time, slow down. understanding that and knowing that you don’t need, as a distance runner, the demands are very different if you’re running, you know, the 400 meter.

400 hurdles or 200, but as a distance runner, a lot of people don’t need super high doses of high intensity to benefit. the risk versus reward often pushes to hire towards that injury risk, especially in athletes with this kind of history. So just kind of sprinkling those foundational principles in about rest is really important. The skeletal reset week that was suggested by Stu Worden. So about every 12-ish weeks, taking a full week off for running.

Jimmy (0.44:34)

which can be really challenging for athletes. that’s also, think how they respond to that can be a little clue to us to the relationship with exercise. And that could be a referral to a licensed counselor or a therapist. If they’re, it’s really challenging or their life is really hindered by taking that week off. So rest, decreasing your intensity and then having these cut back weeks that might be a little bit higher than what was.

your previous. So even having a cutback week is a novel concept to some people where you gradually increase your load and then decrease for a week and then gradually increase. So periodization essentially kind of the manipulation of these variables in a way that we still need more research, but seems to align with what we know about. making sure you have those cutback weeks, deload weeks sounds like being cautious, dosing, high intensity speed work. So with your coaching hat on now, is that what does that mean? Like once a week? What does that mean?

Cause I feel like, so like, I grew up in the collegiate racing scene, like I ran track and cross country in college. And I feel like every college system does about the same thing. We do some sort of intervals. We do a tempo run and we do a hard long run. Like you think, is that too much? Should we do, should I, I’m recovering from a bone stress injury. Should it be once a week? Yeah. What do you think? Yeah. Yeah. I think starting back with once a week and very small, like five minutes total five by one minute or however you want to dose it. So very small amounts initially.

And when you do add intensity, cutting back on your volume. We’re not having an increase or even keeping one stable while you’re adding something else. So we’re kind of manipulating these to reduce bone strain here, add bone strain here. And I think once a week, you know, it’s hard because I think there’s few case studies on this. I know personally once a week or once every two weeks has worked really well. And then kind of working on getting more performance benefits out of strength training.

So, you know, we know that heavy lifting and plyometrics can improve running economy. So again, kind of trading out like that’s, that’s a way to potentially increase performance without the bone load. Keeping intensity at once a week max, that’s high intensity and having more of the like lactate threshold, moderate intensity or tempo work also once a week. That’s typically what I prescribe for my athletes with a straight bone stress injury. And then sometimes that tempo work is within their long run. So it’s one kind of like high quality stress day.

Jimmy (0.46:53)

and then just a lot of easy running. I love it. And yeah, since we’re talking about racing, I wanted to say congratulations on your recent marathon victory. Can you tell me a little bit about it? Stephanie:

Thank you. That was a surprise. I was originally supposed to run the Carmel Marathon in Indiana on April 19th, and unfortunately it had to be canceled the morning of because of storms. no. Yeah, so it was kind of a last minute decision of, right, know, do I just, very happy every training cycle I have. out bone stress injury because I had 12 in a span of probably 15 years.

So, know, yeah, so it was, I just, was me trying to train in a way that I saw other people doing and still not fully taking care of myself from a foundational feeling, sleep, stress perspective. So I learned a lot.

Yes, I think it’s hard there because I think it’s easy to fall into that trap of either comparing yourself to others or comparing yourself to a younger version of yourself and what you got away with in the past. And then that’s like something I’ve struggled with basically my adult life because running in college like my best days are well, I’m never going to run as fast as I ran back then, you know, and it’s I get into that other injury cycles have bone stress injuries, but

other injuries because I keep like hammering what I used to do, which can’t doesn’t work anymore. It didn’t even work back then really. So it’s like hard to it’s a hard lesson to learn. but absolutely. No, I that resonates. really lands. I feel similarly and that it’s it’s really challenging when you have a history of running a certain way and it worked until it did. Right.

And so for a while it just feels like all I have to do is get back to doing that and then I’ll be fine again. But you really just kind of have to shift that perspective. And it’s such a process of accepting where you’re at now. And I think by accepting that, it can open up some other opportunities. Like for me, I feel similarly, you know, we ran fast in high school and college and now it’s like, okay, what are my new goals? Who am I athletically without that? Yeah. But. And it’s like when we’re injured, we, we.

Jimmy (0.49:02)

Your vision is much clearer. feel like you look at your like when I get back to running, I’m going to train smart this time. I’m not going to go above this mileage. I’m going to take two easy days or two days where I do nothing. Yeah. So I guess this is another challenge, but yeah, keep going with your story in this race. Yeah. So it was, then it was kind of a last minute decision to register for OC because it’s

close to Phoenix, could get there pretty quickly. And I think it really helped that I built so much up leading up to Carmel that after not racing, I was like, you know what, I just, I don’t care anymore. I just want this to be over with. I’ll actually have fun, which has been a struggle for me with racing in the past, probably partially due to what we just discussed and having these, these expectations that are maybe a little unrealistic. But I think just having that

perspective of, know what, I’m just going to be running near the beach. It’ll be fine. It’s going to hurt. And it’s just, you know, one of those days where it all just comes together. They’re rare, but I feel very grateful. And that was a big PR for you. Yeah. Four minutes. Four minutes. Nice work. Yeah, that’s awesome. Thank you. All right. Well, I think that’s a good place to start wrapping it up. Guess reflecting back on the conversation, are there any things like you feel like we missed that you would like to like put in here or tell people about?

Stephanie:

No, think just as physical therapists, chiropractors, know, musculoskeletal rehab clinicians, I think it’s just important to know that these aren’t things that we learned previously. So if you’ve missed the SI’s in the past or have a suspicion, it’s okay, we all have. But I think just continuing to keep that on your radar is so important. I know I’ve changed my mind about a lot of things the past several years. And I think that’s very important for all of us to continue to do kind of re-examine our biases.

Jimmy:

That really shows our growth. Yeah. Are there any like specific courses or like resources reading material like really helped you in your?

Stephanie:

Yeah. Rich Willie’s course is awesome. He’s Montana Running Lab. Nathan Carlson and Chris Johnson’s, what is it? Weights? Bones, tendons. Bones, tendons, weights and whistles. Yeah, that one’s been really helpful. My own mentor. Have you seen Chris has his, running essentials, I think it’s called or? I haven’t taken that one yet. Yeah.

Jimmy (0.51:16)

That one’s, I just started to pretty good, but yeah, I’ll second Rich Willie’s course. was great. Yeah. And then for younger, well, not really younger, but clinicians who maybe are experiencing kind of a little bit of questioning of maybe the typical way of doing things and are interested in more of a strength based approach. Clinical athlete is a exercise prescription course that I’m a part of. And so they’ve done such a great job with it. So I highly recommend that as well. Awesome. Are you a reader?

Jimmy:

I am. What are you reading right now? I’m reading Running While Black by Alison Dazir. Yeah, it’s I think, you know, pretty white dominated sport, distance running in the US. I think it’s really eye opening to hear her story on how she’s experienced distance running as a black woman. So I recommend I’ll have to check it out. And then do you have a favorite book?

Stephanie:

Gosh, I don’t don’t think so. I kind of have this thing where sometimes I read books and then I know that they were really good.

But I couldn’t tell you a lot about it. When I’m in it, I can tell you all about I’m obsessed with it. And then when I move on to the next book, it’s a struggle. So I post a lot on Instagram, bone stress injuries, restrictive eating. And my Instagram handle is at stefmonth.dpt. And I have a website, and my company is called Volante PT and Performance. Today, one meeting of Volante is flying or capable of flying. And that’s that feeling that I think.

A lot of us just love and chase when we’re running. And so that is the reason they’re the website is just the lottapt.com and you can contact me through there. Awesome. All right. Anything else before we hop off? Thank you so much.