The ski & snowboard season is officially here. For many of your patients, this means swapping office chairs for steep slopes, often after months of minimal lateral movement. You are likely fielding requests for “ready-to-ski” advice or treating the first wave of early-season knee tweaks.

We know skiing and snowboarding demand a unique blend of endurance, power, and multi-planar stability. But the real culprit behind most ski injuries is not what most people think. It is the combination of asymmetries, limited strength, and stability capacity, as well as poor fatigue resistance.

Each year, Jay Dicharry and his students conduct interesting research into movement and performance. Last year, they looked at snowboarders to understand how asymmetries and capacity limitations affect the sport. This season, we sat down with Jay to discuss how physiotherapists can better stage their skiers and snowboarders so they can enjoy their holiday on the slopes without pain or injuries.

Capacity vs. Skill: The Dicharry Insight

Jay’s recent work with snowboarders highlighted a critical distinction for clinicians: Capacity Limitation vs. Skill Limitation.

Most of your patients fall into the capacity-limited category. They lack the raw strength, power, or stability to maintain proper form throughout multiple ski days. Some elite athletes, on the other hand, can have significant asymmetries but use them to their advantage, jumping higher and executing tricks with precision through superior skill and timing. Recreational skiers with asymmetries face a different challenge: as days of skiing accumulate, fatigue compounds deficits. Muscles misfire, stability erodes, and nagging pains emerge, the kind that force your patient to cut a powder day short or sit out the afternoon run they had been looking forward to.

The Clinical Takeaway:

Identify where your patient sits on this spectrum. If they are capacity-limited (as most recreational skiers are), your goal is to build a robust buffer against fatigue, so asymmetries and weak points do not become the limiting factor by Day 2 or 3 of their trip.

A Practical “Ski-Easi” Assessment Protocol

You do not need a biomechanics lab to upgrade your ski prep. Here is a simple, efficient workflow to add objective data to your standard intake:

- The clinical intake (Standard)

Start where you always do: injury history, ski goals (blue runs vs. double blacks), and current volume as well as life factors that might influence health, performance, and recovery. Screen for red flags like prior ACL reconstruction or chronic back pain.

- The capacity check (Your upgrade)

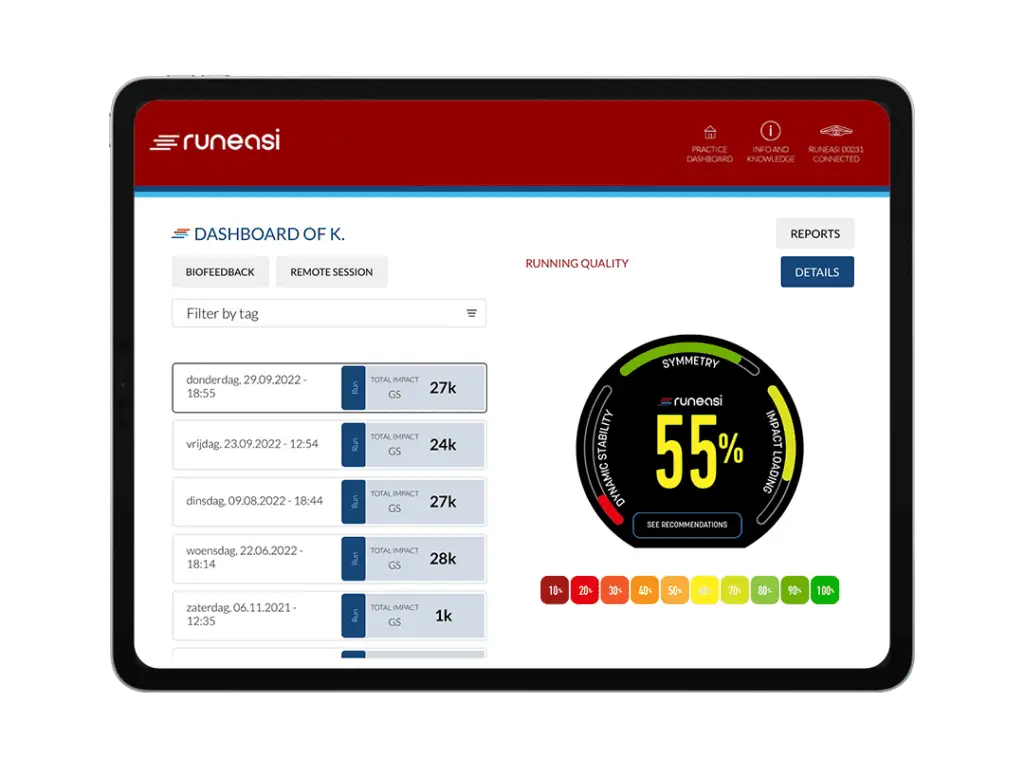

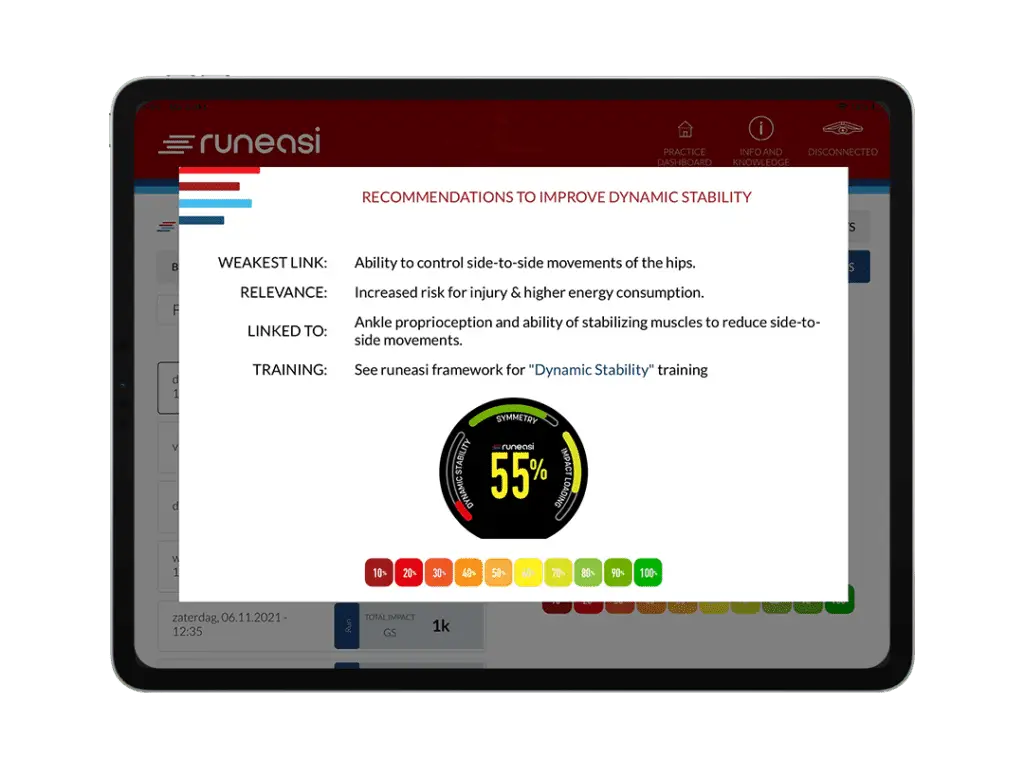

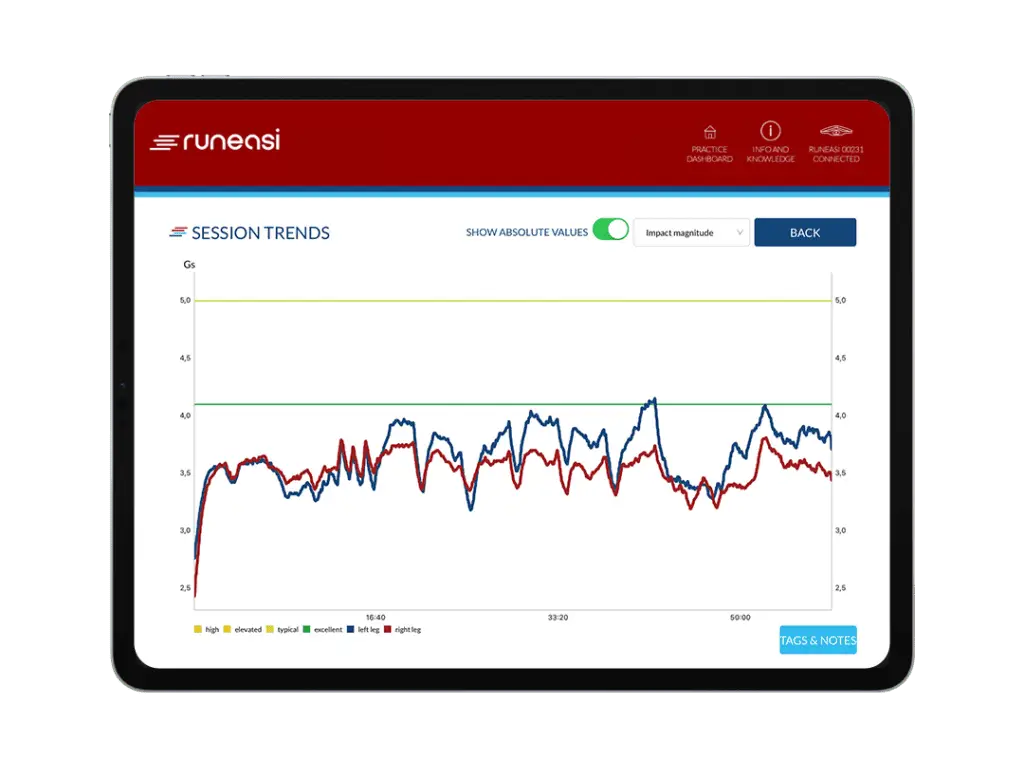

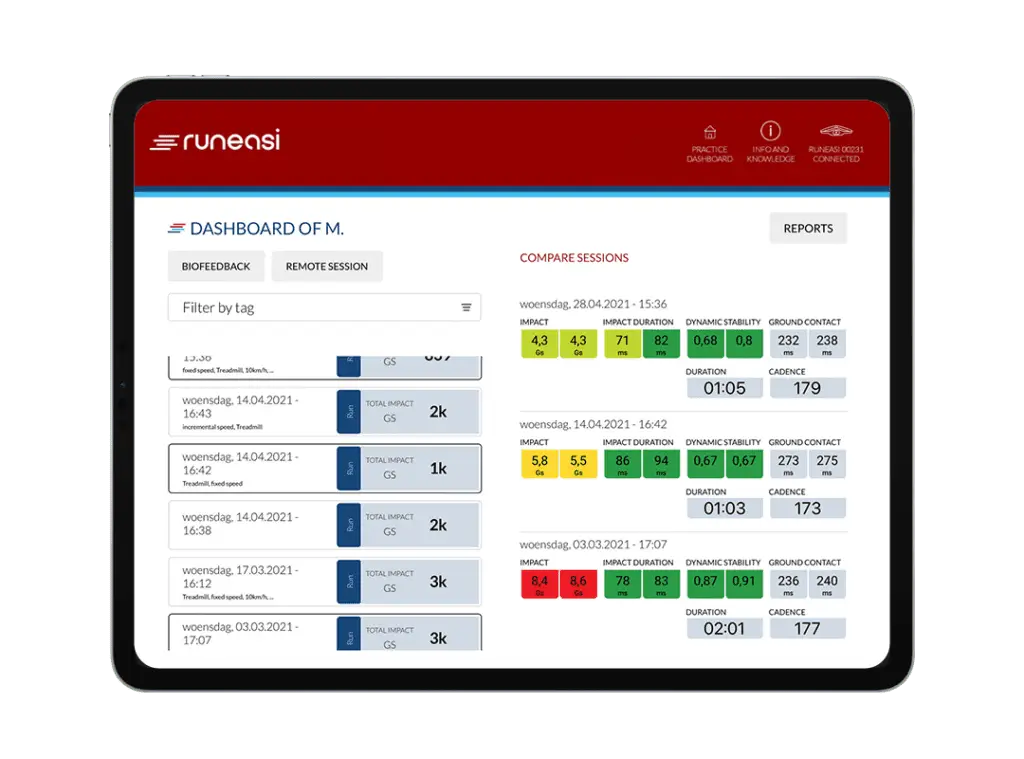

This is where tools like Runeasi shine. Instead of guessing at power or stability, you can use a 5-minute jump protocol to get concrete numbers:

- Squat Jump: Measures maximal power. Can they generate force?

- Double-Leg Hops: Assesses landing mechanics and repeated firing. Can they absorb load efficiently? Combine this with insights on relative strength abilities; look at landing strategies and spring efficiency.

- Single-Leg Hops: The most important. This reveals side-to-side asymmetries in reactivity and ground contact time.

Why this matters: It reveals an athlete’s power, not just how strong they are. The slopes demand that we can recruit our strength quickly; to change direction and jump, but to also keep our joints under control. Peak strength is only part of the puzzle, and the ability to use Runeasi provides a critical lens into their neuromuscular recruitment. A patient might have equal quad strength on the table but can show a notable deficit in reactivity on their left leg during hopping. That is the leg that will fail under fatigue on the mountain. And when fatigue hits hard, it may create issues with that leg, or it more may force them to overload the contralateral leg. Either way, to provide answers to get ready for the slopes requires us to get better insight about the athlete heading to the slopes.

Tailoring the program: from data to snow

Once you have the data, move away from generic exercise sheets. Customize the plan based on their specific deficit:

- For the “Power Deficit” (Low Squat Jump):

- Focus: Explosive capacity to generate force during high demand turns.

- For the “Asymmetry/Stability” Issue (Poor Single-Leg Scores):

- Focus: Unilateral control and landing mechanics to prevent “weak side” collapse under load.

- For the “Fatigue” Risk (Poor overall endurance):

- Focus: Muscular endurance and sustained stability to maintain form across multiple ski days.

The added value

Offering a “Ski-Ready Assessment” isn’t simply good clinical practice; it’s a service patients value. By combining your expert eye with objective data (like “Your left leg reacts noticeably slower than your right”), you give them a tangible reason to stick to their exercises and clear motivation for why the work matters.

Help them glide through their holidays pain-free and keep them out of your clinic for the wrong reasons this winter.

Written by Jay Dicharry, MPT, CSCS

Jay Dicharry built his international reputation as an expert in biomechanical analysis as Director of the SPEED Clinic at the University of Virginia. Through this innovative venture, Jay was able to blend the fields of clinical practice and engineering to better understand and eliminate the cause of overuse injuries in endurance athletes. His unique approach goes outside the traditional model of therapy and aims to correct imbalances before they affect your performance. Jay wrote a book on running gait assessments: he is author of "Anatomy for Runners", writes columns for numerous magazines, and has published over 30 peer-reviewed journal articles. Having taught in the Sports Medicine program at UVA, he brings a strong bias towards patient education, and continues to teach nationally to elevate the standard of care for Therapists, Physicians, and Coaches working with endurance athletes.

Originally from New Orleans LA, Jay completed the Masters of Physical Therapy degree at Louisiana State University Medical Center and is a Board-Certified Sports Clinical Specialist. Jay has had an active research career, and consults for numerous footwear companies, the US Air Force and USA Track and Field. His research focus on footwear and the causative factors driving overuse injury continues at Rebound, and provides his patients with an unmatched level of innovation and success.

In addition to his clinical distinction, Jay is a certified coach through both the United States Track and Field Association and the United States Cycling Federation, and certified Golf Fitness Instructor through Titleist Performance Institute. He has a competitive history in swimming, triathlon, cycling, and running events on both the local and national level, and has coached athletes from local standouts to national medalists.